November 2, 2021

Being able to breathe requires keeping authority in context

iStock / People Images

Emphasis on the inerrancy and infallibility of the Bible suffocates those who function outside the construct of whiteness, writes an assistant professor at the McAfee School of Theology.

As a scholar of the New Testament who is also an African American woman in the context of the United States of America, I struggle with the idea of being a serious scholar while also attempting to write and teach in a manner that takes seriously the real and lived experiences of other Black women in faith communities across the country.

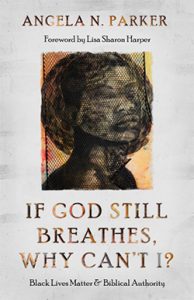

In my book “If God Still Breathes, Why Can’t I? Black Lives Matter and Biblical Authority,” I begin to tackle these struggles by engaging breath as a metaphor. I describe my book as “part memoir, part biblical scholarship” as a way to show that these struggles are real.

I often ponder this metaphor through the prevailing cultural lens of “The Bible says it; I believe it; that settles it.” In my teachings and writings, I am trying to understand that adage as being connected to a Eurocentric worldview that produces a specific understanding of inerrancy and infallibility as tools of what I identify as white supremacist authoritarianism.

I argue that this worldview actually constricts breathing and highlights the connections between such suffocation in particular faith communities and the cries that have been vividly recorded in the many Black and brown men and women killed as a result of police violence.

In my own faith walk and in conversations about breathing, I have tried to develop a standpoint on authority that expands beyond inerrancy. Since the Bible, as the word of God, is seen as the ultimate authority in many faith communities, I ask how we can question the biblical text while still holding on to a modicum of authority that is not authoritarianism.

One of the ways that I expand upon my students’ understanding of authority and authority’s relationship to the Bible is to set it in a broader context — not in the context of a Eurocentric worldview alone. Understanding the Roman imperial context becomes important in broadening a student’s view of authority.

The English word “authority” derives from the Latin word auctoritas. In Roman imperial society, auctoritas is distinct from the word imperium.

Imperium (from which we get “imperial”) connotes the idea of rights held by government officials. In contrast, auctoritas allows for the interpretation of and elaboration upon the wisdom of those who came before.

As Old Testament scholar William Brown notes, auctoritas is more creative. While precedent matters when it comes to auctoritas, what matters more is having conversations with what comes before and after.

The idea of authority actually stems from movement between interpretation and contextualization. In many ecclesial settings, I still experience pastors and ministers interpreting texts without deep and thought-provoking contextualization.

As a biblical scholar, I understand the importance of contextualization as a part of interpretation; however, many students — and even some preaching pastors today — do not. Within my family, relatives sometimes ask me during visits what I think of a sermon. And often, I regale them with contextualization of the biblical text that they do not hear in their ecclesial lives.

How would our faith communities be transformed if we fully embraced an idea of biblical authority that lives and breathes in such a movement between contextualization and interpretation? How would our faith communities transform society if we embraced the need for an abiding sense of connection to what has happened in the past while having continued conversation with our present and imagining what future transformation could entail?

Furthering the authority conversation, Katie Cannon shows how African American professors depart from the “normative” (read: “white male”) assumptions in our various guilds to bring a radical critique to inherited Eurocentric traditions and kerygmatic assertions that minimize Black people’s actualization of our God-given authenticity.

As I engage biblical texts, I employ Cannon’s idea of departing from the normative ways of reading by maximizing the authority within one’s own identity to actualize the individual reader’s ability to exert our God-given, inspired breath — our authority.

Part of my job as professor is to develop a creative understanding of biblical authority propelled by and enabled by a God who continues to breathe in and through the interpreter today. Such a creative understanding allows students to imagine readings of Scripture that foster a healthy society in which all participants are able to make distinctive and valuable contributions and therefore breathe!

As readers engage my work, my hopes and prayers are that faith communities will expand conversation around issues of biblical authority that take seriously a multiplicity of identities and the ways that various identities read biblical texts. I believe that it is only after we are forthcoming and mature enough for such conversations that we can begin to imagine faith communities that are truly multiethnic and multicultural.