November 15, 2022

Luke A. Powery: The Holy Spirit can inspire us to understand one another’s humanity

The Holy Spirit is key for Christians looking to communicate across divisions, says the dean of Duke University Chapel.

For Luke Powery, it’s significant that different people heard their own native tongues from strangers’ mouths at Pentecost.

The impact of being able not only to understand another’s speech but to hear a familiar language from a stranger could provide a road map to navigating division.

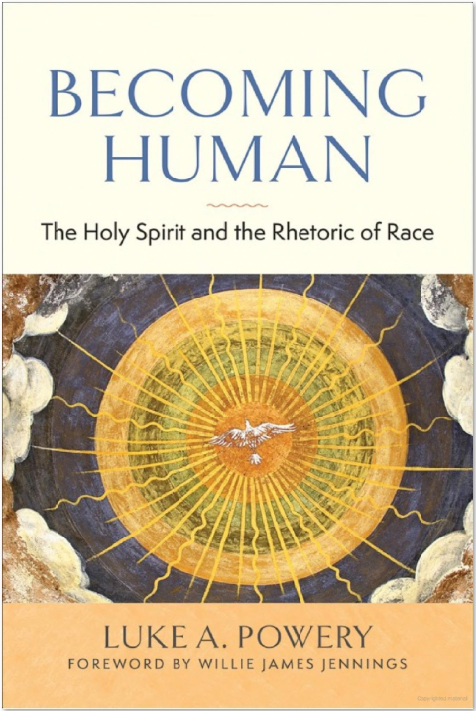

Turning to the Holy Spirit and Pentecost as a means for re-imagining human relationships and pushing past divisions created by racialization is the subject of Powery’s recent book, “Becoming Human: The Holy Spirit and the Rhetoric of Race.”

“A turn to the Spirit is a turn to the human,” Powery writes.

Rather than a call to uniformity and dropping conflict, the Holy Spirit’s work at Pentecost is a testament to how unity and diversity coincide for Christians.

Powery is the dean of Duke University Chapel and an associate professor of homiletics at Duke Divinity School.

He spoke with Faith & Leadership’s Chris Karnadi about the book and how the Holy Spirit can inspire us to become more human. The following is an edited transcript.

Faith & Leadership: How did the pandemic influence your writing of this book?

Luke Powery: I gave three lectures at Austin Presbyterian Theological Seminary around “Searching for Common Ground,” playing off Howard Thurman’s book “The Search for Common Ground,” and that was right before COVID, actually, in February.

Through everything in the pandemic, I think what was striking to me was our mortality as human beings and thinking about our shared humanity or lack thereof — the tensions that there were over mask wearing or not, the tensions between human beings across racial divides because of the murder of George Floyd.

The book is focused on those dividers, adjectives, whatever you want to call them, that have functioned in a way to separate people and not embrace our mutual humanity.

The pandemic brought everything to a head in many ways — our striking mortality as human beings. The pandemic should have been a time to help us get things in order, at least get our lives straight, our minds right, and it just, I think, became more tense and polarized. And so it was this call, which I have at the end of the book — a call to togetherness.

Ultimately, that’s what’s behind the book, this call to reconciliation. I try not to use that word, because it’s overused, but I think fundamentally, the book is a call to come together as children of God regardless of who we are, and trying to ground that in a kind of pneumatology.

As Thurman says at King’s funeral when he eulogizes, “We’re not quite human yet. We’re becoming human.” I think those words are so true for where we are today in this nation and really in the world. We’re not quite human yet.

F&L: How does the Holy Spirit change or work against the racialization of our world?

LP: For me, Pentecost is a metaphor for the gift of multiplicity that we see in languages, cultures, ethnicities. There is the embrace of, or the affirmation of, difference, and there’s not a hierarchy created.

It’s really this diversity unified. So racialization is a de-affirmation or a mode of dehumanization of the other, whoever that might be, in a kind of racialized hierarchy.

At Pentecost, there isn’t a hierarchy, and what’s central — or who is central — ultimately at Pentecost is God, and it’s not even our own particularity. Our particularity is not erased; it’s affirmed.

God is central, and God is the one who can bring us together. And so for me, what we have is this affirmation of the beauty of humanity.

At Pentecost, it’s not just the gift of speech but the gift of hearing and understanding in your own native language. What’s interesting is people are hearing their own native tongue in the mouths of the other who’s someone who’s different, not even somebody from their own ethnic background.

I think the Spirit drives us, leads us to a coming together, to unity, to mutual understanding, to the bodies that are again affirmation of the bodies of people, of all people, and as gifts of God. And so diversity, or difference, however you want to say it, is the gift of God.

It’s not something to be avoided or sort of ignored even. It’s the gift of the heterogeneous expression of the Spirit; that’s the gift.

Homogeneity and uniform communities are not the gift of the Spirit. It’s unity and heterogeneity; that’s the gift. And so the Spirit, I think, helps in opening that up in a way to help us embrace the humanity, no matter how different, of someone else. It actually affirms the humanity of others.

F&L: What do you think that unifying power of the Holy Spirit looks like in preaching?

LP: From the pulpit, it’s what our telos is as preachers. Is our telos to divide, or is our ultimate goal the move toward unity? Again, unity implies diversity, so it’s different from uniformity.

It doesn’t mean every single sermon is on a specific topic, but what is your thrust? Is it to see a community really be a community, which means it being diverse and not functioning with this racialization, which is dehumanization, but really seeing people as people?

There’s an overall thrust as preachers and in the community. How do we at the church find a new tongue, playing off Pentecost? How do we find a new language? How do we find a new way of talking about human relations?

I say “racialize” or “racialization” quite a bit in the book; I do that intentionally, because it’s something that’s done to us. It’s not something that is ontological. It is something that’s social.

We have this social inheritance and historical inheritance of race as a social construct, and obviously it’s shaped how things are in the world. It’s not as if we can erase that and say, “Oh, we’re going to change how we talk, and things we can do better.” But I think there is a way that we can talk about relations with each other across these divides that might be more helpful, more Christian, more Spirit filled.

Identities can become idols, and so before we even see someone else as a human being and talk to them like a human being, we’re already thinking whatever categories they are, whether it’s political affiliation or what we see them to be racially.

We don’t see them as a human being, a brother and sister. In the church, how can we find a new way, a new language? What is the more human way and more humane way for talking about these things in the church?