Empowering teens: Youth learn job skills and serve their community through a workforce development program

The unmistakable scent of curry permeates the spacious commercial kitchen in Richmond, Virginia’s East End, where a half-dozen teenagers in spotless white chef coats are sharpening their culinary skills while feeding their community.

The teens scrub, peel and chop several buckets of turnips and radishes donated by a nearby farm, the rhythmic ka-THONK, ka-THONK of metal knives against plastic cutting boards broken only by whispered guidance from chef Duane Brown: Slow down, slow down. Take your time. And watch your fingers. Yep, yep, perfect.

Brown, a graduate of the Culinary Institute of America, has been meeting weekly since November with some of these teens, teaching them first the art of “mise en place” — having all needed tools and ingredients organized and close at hand — before branching out into food prep and production. On this particular evening, Brown will show them how to braise the chopped-up root vegetables in a curry sauce before pouring them over a bed of steamed rice and dividing them into 50 separate meals for low-income seniors and families in a nearby apartment complex.

At one end of a prep table, 16-year-old Malachi Sottile scrutinizes a red onion before peeling and finely dicing it. Sottile said he’s always enjoyed cooking. He was learning some tips from his grandmother before enrolling in the culinary training class, which falls under the auspices of Church Hill Activities & Tutoring, or CHAT, a nonprofit where Brown serves as the director of workforce development. Sottile’s skill set has expanded considerably over the last seven months.

“At first, it was challenging, keeping track of all the new information,” Sottile said. “But after a while, you get the hang of it.”

Alongside their knife skills, class participants pick up life skills, learning the importance of showing up on time, asking for help, working with a team, focusing on a task and communicating clearly, Brown said. At the end of the day, participants are gaining not only the ability to earn a paycheck but also the confidence to try new things, solve problems and advocate for themselves.

In addition to offering culinary training, CHAT operates three distinct businesses that also serve as training grounds for young people in an economically depressed part of Richmond: a coffee shop and cafe, a silk-screening studio, and an urban farming outfit that includes a cutting-edge hydroponic grow operation. Those businesses employ about 20 young people, most between the ages of 16 and 22; last year, 51 young people either worked for one of CHAT’s enterprises or participated in its training programs, said Hannah Teague, the director of marketing and communications for the organization.

“Ultimately,” she said, “as an organization, we want to create more and more opportunities for students and young people to help them grow personally, spiritually, socially and academically so they’re ready for whatever’s next.”

Which programs and ministries in your community help people advocate for themselves and their neighbors?

‘A rebalancing of the scales’

CHAT has what Teague calls a “scrappy origin story.” It launched in 2003 after a couple moved into the Church Hill neighborhood and turned their front porch into an informal gathering place, where neighborhood children could safely hang out and get some help with their homework. They were part of a wave of Christians, mostly white, who began moving into Church Hill from the suburbs, hoping to advance the cause of racial reconciliation and redevelopment in the state’s capital city.

That couple has since moved to South Carolina. But with guidance from the community, CHAT has expanded its scope, formalizing its after-school program, opening a fully accredited private Christian high school with priority given to low-income students from Richmond’s East End, and adding workforce training.

While there are spiritual components to CHAT’s programs, students can be of any faith — or no faith, and the organization doesn’t consider evangelism to be a primary focus. But, Teague said, “Christianity is in the ethos of everything we do.” In addition, she said, in a place that was once the capital of the Confederacy, CHAT’s programming is meant to prioritize the Black experience and center Black voices.

Brown said the seeds of CHAT’s workforce development piece were planted around 2005 or 2006 when the nonprofit launched Nehemiah’s Workshop, a woodworking operation where students handcrafted coasters, charcuterie boards, tables and rocking chairs. Jobs in the neighborhood were scarce, he said, and CHAT wanted to offer young people a “wholesome” activity where they could learn a lucrative trade.

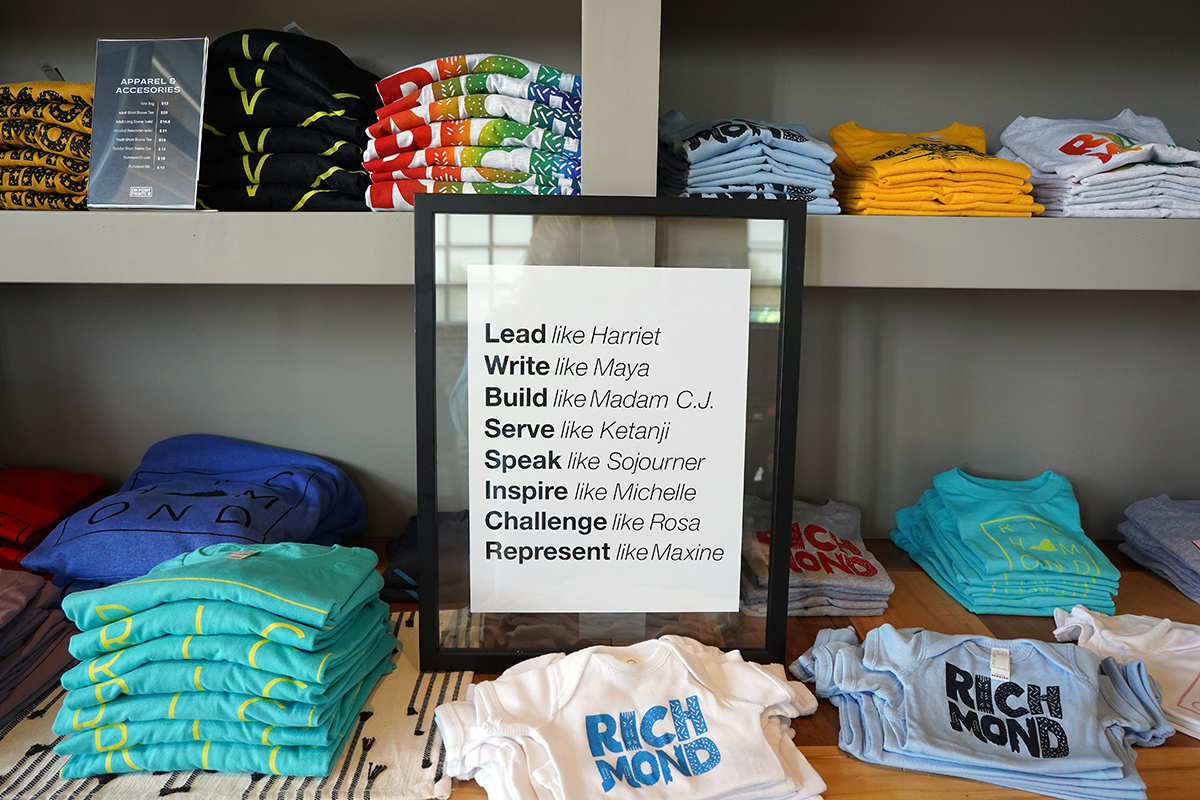

Next came lessons in sewing and silk-screening, which led to the creation of On Point Prints, a screenprinting studio that produces everything from tote bags and T-shirts to tea towels and hoodies.

In fall 2017, CHAT opened its primary food service training facility, the Front Porch Cafe, which is a breakfast and lunch spot housed in the Bon Secours Richmond Community Hospital’s Center for Healthy Living. There, about a mile north of CHAT’s main office, diners settle into comfy blue easy chairs while enjoying pastries, coffee, tea and sandwiches.

Framed photographs of neighborhood residents enjoying their front porches adorn the exposed brick walls of the interior. And some of the ingredients used in the cafe’s meals are grown at Legacy Farm, an urban gardening project, which encompasses a few parcels on CHAT’s quarter-acre property and some space in a church-owned greenhouse nearby.

Whose voices are centered in your work? Whose voices are minimized or missing entirely?

In addition, CHAT was invited last year to participate in a three-year pilot project, where students learn how to grow microgreens using hydroponic equipment. The equipment was purchased and installed by Dominion Energy, and maintenance and seeds are donated by Richmond-based Babylon Micro-Farms.

The entire nonprofit has an annual budget of about $3 million, most of which comes from private donations. Roughly 20% of that is set aside to support workforce development, said Jonathan Chan, CHAT’s executive director.

CHAT’s businesses are not motivated by profit as much as by a desire to equip young people with life and professional skills, so the enterprises are not expected to be self-sustaining. The goal, said Brown, is for the revenue from each business to cover about 80% of its expenses.

While not focused purely on money, the effort is still strategic. The organization paused Nehemiah’s Workshop to assess and research similar trainings and to gain a better understanding of the industry trends and student interest. The primary focus is on aligning with regional workforce goals and technology. Some of the workshop’s woodcraft items remain for sale online, as are items from On Point Prints. Shoppers can also pick up On Point’s tote bags, T-shirts and onesies inside the Front Porch Cafe.

All of the businesses have popped up at local farmers markets and neighborhood festivals to showcase their wares. The culinary trainees have hosted cooking demonstrations and tastings for family, friends and cafe customers. And, in anticipation of sourcing its lettuce from the hydroponic farm this summer, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts invited the Front Porch Cafe staff to host a pop-up event in late May, debuting its Summer Crunch salad, a mix of green leaf lettuce, quinoa, carrots, lentils, almonds and an apple cider vinaigrette that will be featured in the museum’s cafe.

Rebranding and exploring

Because the organization has evolved quite a bit over the last two decades, Teague said, CHAT is working on a rebranding effort that draws clear connections between all of CHAT’s initiatives: the social-emotional work of the after-school care program, the academic focus of the high school, and the vocational aspect of the workforce training initiatives. The organization is also exploring how best to leverage its connections to alumni so they can share their talents and life experiences with CHAT’s current participants.

Gentrification within the Church Hill neighborhood is also a challenge CHAT is trying to address, Chan said. Rising property values have meant that some of the families the organization has traditionally served have been pushed into neighboring communities, leading CHAT to expand its own service area beyond Church Hill proper into Richmond’s East End — even as far as neighboring Henrico County.

Right now, CHAT’s main office, along with On Point Prints and the Legacy garden, stands in the heart of Church Hill, within walking distance of several elementary schools and a Boys & Girls Club. But that may need to change down the road as families are displaced, Chan said.

The young people who participate in CHAT’s programs are full of promise, and their drive challenges false notions the general public may have about people who live in the East End of Richmond, Chan said.

How do your organization’s structure and work evolve when situations change? How do you transition out of what is no longer possible and refocus on what is?

“I think we want people to have a sense of the potential, assets and gifts of our students and that we have a rebalancing of the scales to do. We want people to interrogate their own assumptions of how the world works,” he said. “If they have negative perceptions of Black and brown students, the people who live in this area, we want those to change, to be disrupted, so they can learn how they can be part of God’s work of justice.”

‘They truly want to help you grow’

In a cramped room at the rear of CHAT’s headquarters, Timond Billie, 19, is flooding a silk-screen frame with all the colors of the rainbow to create one of On Point Prints’ popular tote bags. A senior at Church Hill Academy, CHAT’s private high school, Billie said he started working at the shop in October 2021 after hearing about it from his twin sister, Jamea, who had completed a six-week summer internship there.

How does your organization contribute through disruption to God’s work of justice?

Billie said he hopes to pursue careers in music production and real estate. The networking and marketing skills he’s picked up at On Point will help with both of those pursuits, he said. And learning about color schemes and design should come in handy when it comes to flipping houses, he said.

“I didn’t know there were so many colors — or that you could make colors out of other colors,” he said, laughing, as he pulled a squeegee through the ink, pushing the colors through the screen and onto the canvas bag beneath his tray.

Initially, Billie said, he was anxious about interacting with other people. But On Point manager Stephanie Albert was so welcoming, encouraging him to work at his own pace and to just be himself, he said, that he quickly felt comfortable. And after selling items at the neighborhood farmers markets, he doesn’t worry about chatting with strangers anymore, he said.

“I used to be really shy. But you’ve gotta break out of your shell,” Billie said. “Now, I’m confident with it.”

Like Billie, most of those who apply to CHAT’s training programs or to its job openings hear about those opportunities through word-of-mouth. Brown said he’s in regular contact with local schools, pastors and community liaisons in nearby housing complexes, letting them know when positions and new training programs open up.

In terms of tracking the progress of the program’s participants, Brown monitors whether they show up consistently and on time, how present they are when it comes to listening to instruction and completing tasks, and how well their communication skills progress, he said.

Though each workspace is a little different, Brown has accessed some youth-specific tutorials and webinars through the Federal Department of Labor’s WorkforceGPS, he said, and has gotten good advice from Catalyst Kitchens, a national network of nonprofits and regional workforce boards that operate cafes and restaurants offering job training and life skills exposure. Brown said he also makes use of industry tools, like keeping track of how many culinary trainees go on to earn their ServSafe certification through the National Restaurant Association.

The top measure of success, however, is how well CHAT instills confidence in those who participate in its workforce training initiatives, Brown said. Many of the young people who work for CHAT’s enterprises have never held a job before, he said, and many of them have little, if any, exposure to life management skills. Some face challenges with housing and transportation or are self-conscious about their struggles with math or reading comprehension. But Brown works hard to earn their trust and make CHAT a space where they feel safe enough to be honest about their needs and their goals. It’s rewarding when they share their victories with him, he said.

“There’s a point in the mentoring process where they’ve launched or moved on and you kind of stop hearing from the students,” Brown said. “And then you hear, ‘Hey, I’ve got this job interview.’ Or, ‘I got my ID.’ Or, ‘I got an apartment and a full-time job.’ And they’re demonstrating that they’ve got what they need and that they feel self-sufficient.”

Mareesha Randolph, 20, said she never really felt free to express herself or speak up about how others made her feel when she worked in retail.

“I kind of just stood in the shadows,” said Randolph, who applied for barista training at the Front Porch Cafe after a friend who was familiar with CHAT recommended it.

On her first day of work, Feb. 27, she met fellow trainee Rashá Coleman, 19, and the two have basically been finishing each other’s sentences since then. Both women said they were encouraged to ask questions and try new things, something they hadn’t experienced at their previous jobs.

What’s the word-of-mouth about your organization and its work within the community?

“With other jobs, they just throw you right in. And back in my old job, they used to stand over you,” Randolph said. “Here, if you need help, they’re here for you, but they’re not all in your face. Over here, it’s OK to make a mistake.”

She said she still gets nervous every time she hands a customer a cup of coffee, worrying about whether she nailed the order or not. But it’s gratifying when the person takes a sip and smiles or gives her a nod of appreciation, she said.

“You shouldn’t let fear stop you from doing things you could be great at,” Randolph said. “It’s OK to try new things. That’s how you figure out what you like and what you don’t like.”

Randolph said she’s been surprised by how much she’s learned, everything from how to steam milk “so it’s not screaming at you” to how to create latte art — she’s recently mastered making a heart pattern.

She hopes to use the practical skills to get a job at a coffee shop in New York when she moves there in the fall for acting school. But the other experience she’s gained — speaking with members of the public at pop-up events, working during the high-pressure lunch rush, learning how to read customers’ body language and respond with empathy — will be invaluable in any work environment, she said.

“They’re just so friendly, and you can feel that they truly want to help you grow. They gently push you into the areas you need,” Randolph said. “And the way they do it, you didn’t realize you really needed those skills until you have them.”

Questions to consider

- Which programs and ministries in your community help people advocate for themselves and their neighbors?

- Whose voices are centered in your work? Whose voices are minimized or missing entirely?

- How do your organization’s structure and work evolve when situations change? How do you transition out of what is no longer possible and refocus on what is?

- How does your organization contribute through disruption to God’s work of justice?

- What’s the word-of-mouth about your organization and its work within the community?

It dawned on the Rev. Sarah Taylor Peck in fall 2019 that she’d shared a pastoral moment with every household in her Disciples of Christ congregation. As the senior minister at North Canton Community Christian Church for nearly six years, she had officiated at their weddings, taught their children and helped bury their loved ones.

Nearly 200 worshippers showed up weekly for the Sunday morning service, and she had forged deep, meaningful relationships with each one of them. Taylor Peck felt genuinely honored to be part of the community they’d built together.

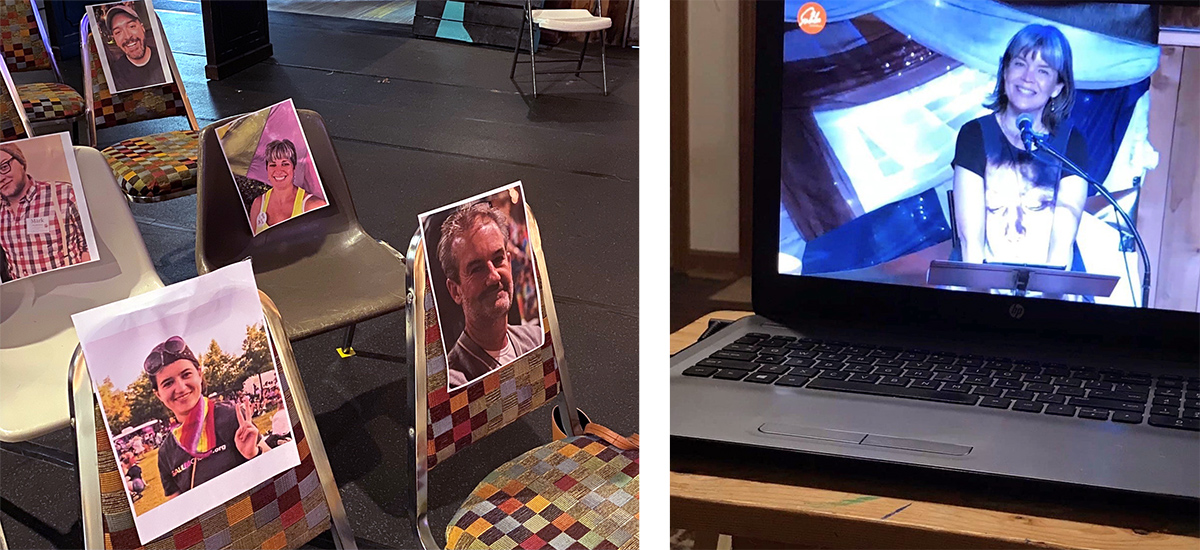

Then the pandemic struck, closing the Ohio church’s doors and forcing their fellowship into the ether. The congregation reopened for good during Lent 2021, but not everyone has returned for in-person worship. Coming to church each Sunday takes discipline, Taylor Peck said, and like a muscle that goes unused, it atrophies over time.

“I’m still in a season of lament about the way the pandemic contracted congregations and congregational ministry,” she said shortly before Christmas. “It really broke the tether we had to our members.”

All is not lost for North Canton Community CC. While Sunday in-person attendance is down about 30% since before the pandemic, nearly two dozen new people joined the church in September, the largest single class of new members since Taylor Peck arrived in January 2014, the pastor said. She is profoundly grateful for their enthusiasm and this opportunity to rebuild the church’s community “bit by bit, moment by moment, sacrament by sacrament.”

But she also misses the families who have yet to return and isn’t entirely sure what, if anything, she can do to convince them to come back. One day, Taylor Peck dropped by the home of a longtime church member who hadn’t returned to in-person worship. Bearing flowers from the altar, she told the 82-year-old that she missed him, that his church needed him and that she hoped he’d come back. His response: he simply wasn’t getting dressed in the mornings anymore.

There are plenty of others just like him, Taylor Peck said. They didn’t leave in a huff; they simply altered their routines during the pandemic, and in-person church attendance isn’t the priority it once was.

“They didn’t get mad at our policies and stomp away. They’re just not coming,” Taylor Peck said. “I almost prefer a fight. There’s emotion and commitment in a fight. But this is just apathy. It’s less vigor for church.

“We can’t tempt them or bait them or inspire them to come. We have to wait patiently. So we begin again.”

How have the expectations that pastors and congregations have for each other changed over the last three years?

Nearly three years after COVID-19 upended life as we know it, faith leaders like Taylor Peck are pondering how best to mourn and honor what was lost while reengaging communities that have irrevocably changed. How do you recalibrate for absences associated with deaths that couldn’t be properly grieved? How do you account for those who vanished for political reasons? And how do you build meaningful connections with virtual worshippers who might never enter the building?

“The ministry of church isn’t just about Scripture and gospel. It’s reminding people how to do life together, how to show up together,” said Taylor Peck. “I would hate for that to be lost.”

North Canton practices communion weekly. What influence do your congregation’s worship practices have on expectations for in-person attendance?

Not just COVID concerns

At Holy Trinity United Baptist Church in Washington, D.C., the pews aren’t as crowded as they once were, said the Rev. George C. Gilbert Jr., who serves as the assistant to the pastor, his father. He attributes some of those absences to lingering fear over the coronavirus, a very real concern for older parishioners, including his 75-year-old father, the church’s founder, who spent two months battling the virus.

While statistics indicate that the chances of catching the virus and dying from it have decreased considerably since the pre-vaccine days of the pandemic, “fear versus faith is still a very tense conversation” within the church, and most of the congregation’s older members remain masked and socially distanced when they attend worship, Gilbert said. Those are the stalwarts who find a way to come together despite their concerns.

It’s the younger folks who remain missing on Sundays, Gilbert said, and he’s not convinced that COVID concerns are driving that absence. He sees crowds of young people, masked and unmasked, at grocery stores, the mall and birthday parties. Between the pandemic and ongoing political strife, he said, he worries that people are leaning more toward culture and less toward the Holy Spirit.

“None of those places is lacking attendance. They all seem to be at capacity,” he said. “But when it comes to church, we have to ask ourselves, is it about commitment or is it about the virus? The world is in competition with God.”

Indeed, a recent study by the American Enterprise Institute and NORC at the University of Chicago found a drop-off in church attendance among younger churchgoers, as well as those already less connected with a faith community and those who identify as liberal.

Holy Trinity has persuaded some young people to return by giving them tasks that appeal to their skill sets, Gilbert said. Younger members helped the church choose an online giving platform, something the congregation hadn’t offered pre-pandemic. They’re running the church’s social media channels and handling the tech needed for livestreaming services. And a group of them created a praise team that sings every Sunday, partly because they’re not as anxious as some of the seniors about catching a respiratory illness, Gilbert said.

The church has also expanded its outreach, recently approaching a local homeless shelter about starting a church for its residents.

“We know folks are afraid to come out. They’re just not ready to come back to church,” he said. “So we’re trying to go to them and make Jesus as accessible to folks as possible.”

Gilbert said the empty pews weigh on him and he wonders what God is asking of him, whether there’s something else he should be doing to engage his community.

“If folks don’t come back, it’s hard for us not to see ourselves as a failure. That’s the stress of being relevant,” Gilbert said. “But God doesn’t call us to be relevant. He just asks us to be faithful.”

What worries you about the shift in patterns of attendance? How can you distinguish your own grief from your analysis of the situation?

The Rev. Dr. Rolando Aguirre started as an associate pastor at Dallas’ Park Cities Baptist Church the first weekend in March 2020. His work, focused on teaching and Spanish language ministries, began just as the world was beginning to shut down. The ensuing months were marked by resetting, relaunching and, ultimately, reopening.

Aguirre said the majority of the people he expected to serve have not yet returned to church, and he suspects many have relocated. But new people are coming, and Park Cities is responding to possibilities that the pandemic surfaced. Lay leaders have engaged more actively in reaching out to members.

“The fellowship of deacons were more active in saying, ‘Let’s help call the people. Let’s encourage them to come back. Let’s visit them.’ So last year was a lot of the leadership base [responding] to engage with the congregants,” Aguirre said.

They are also addressing needs that emerged – offering monthly Spanish-language services at additional sites, and responding to a desire for more youth programming and a need for mental health support.

A congregational survey along with group and individuals interviews helped “to really recapture, recalibrate our vision,” he said.

Sampling online services

At Pelion United Methodist Church in South Carolina, Sunday attendance is down a bit from before the pandemic. The Rev. Ed Stallworth attributes some of the loss in his congregation to Christianity being politicized.

“That’s become a bigger disease than the pandemic,” said Stallworth, who became the pastor at Pelion UMC and nearby Sharon Crossroads United Methodist Church in July 2021. Prior to that, he’d served at a progressive church in Spartanburg, South Carolina, and his arrival in conservative Pelion, about 20 miles outside the state capital of Columbia, made more than a few worshippers nervous, he said.

One of the first questions he was asked was whether he’d “force” worshippers to wear masks. He responded that he couldn’t force anyone to do anything but that he and his family would mask up to keep everyone safe. And he’s openly encouraged members to get vaccinated.

Some ultimately left over political differences, Stallworth said. But he’s encouraged those who remain to embrace the church’s growing diversity and learn to worship alongside people who don’t necessarily share the same opinions.

“I said, ‘We may disagree, but just know that I’m going to love you through everything,’” Stallworth said. “And they took hold of that. I think that’s how we got through this pandemic and how we’re going to move forward together.”

Both churches developed a virtual worship option, said Stallworth. While serving his church in Spartanburg, Stallworth broadcast a 30-minute service on Facebook, using his cellphone and laptop, with accompaniment from the church’s organist. Some days, he misses the solitude of that effort, so he understands why some of Pelion’s members still prefer to worship from home.

Most of the worshippers now attending in person are new, having sampled the church’s services online before ever coming into the building, he said. And the majority of them were previously unchurched, he said. Many of the newer members are young people with children who were introduced to Pelion UMC through its outreach programs, like Trunk or Treat or its school backpack program.

“They just want to be part of a community that’s bigger than them. I think they just want a sense of, ‘We’re going to be OK,’” he said. “Contrary to what a lot of people are saying, I believe better days are ahead for the church. It might look different, … but particularly for progressive congregations, from these ashes something beautiful is going to emerge.”

How is the work of supporting the ministries of the church changing? What are the skills and experience needed to offer ministry today?

Pentecost moment

The Rev. Justin Coleman, the senior pastor at University United Methodist Church in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, also maintains a sense of optimism about the church’s future. Pre-pandemic, the church invested in a new sound system and video cameras, primarily to reach the homebound and the nearby academic community, many of whom left town during the summers but wanted to remain connected. That investment proved crucial during COVID-19 when the church moved entirely to virtual worship.

Members of the congregation who disagreed with that decision ultimately trickled away in favor of churches that either resisted shutting their doors or reopened sooner for in-person services, Coleman said. But the church has since welcomed a host of new members, many of them young families, who initially connected with the congregation online and now attend in person.

Plenty of University UMC’s members still prefer what Coleman calls “couch worship,” and he said they’ve “stopped being apologetic about it.” But he doesn’t view virtual participation as a negative.

Prior to the pandemic, some members would come to church once or twice a month but wouldn’t necessarily go online to watch a service. After the pandemic normalized remote worship, many of those folks became regular online worshippers who also tuned into Coleman’s podcasts.

“For them, they’ve increased the amount of time they’re connecting with worship or a worship-related activity,” Coleman said. “The question we’ve begun to ask now is, ‘Should we not just treat this like a proper digital campus?’ These people are worshipping at home. How do we interact with them to help them feel connected and share opportunities to serve?”

The church has considered designating a staff member as a “digital usher” during the livestreamed service and establishing a small group that meets online. Coleman acknowledged that clergy are “chock-full of nostalgia and sentimentality,” which can make it challenging to embrace the kind of radical change churches are facing post-pandemic. But churches need to stay nimble, he said, noting that the Pentecost moment is about cultural adaptability.

“That’s God saying this gospel is going to move into the culture in many ways, and what’s implicit is this is going to look different as it moves into all those places,” he said. “I would love to have multiple services filled with people who want to be there in person. On the other hand, people are connecting with us in new ways. How can we capitalize on this and reach more people in more places with the gospel because of this opportunity with technology?”

What is the ratio of in-person to virtual attendance in your congregation? What questions about the vitality of the virtual congregation are being raised for you?

New front doors and back pews

The Rev. Dr. D. Dixon Kinser, the rector at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, calls the congregation’s livestreamed worship service — created in response to the pandemic — “the new front door of our church,” noting that most of its new members first participated online.

Before the pandemic, Kinser worried that online worship would be too “performative,” but he’s since come to appreciate the accessibility livestreaming offers. He said worshippers have enjoyed being able to attend services even when they’re out of town, and one member was recently able to participate in a service while hospitalized.

Though in-person attendance is down, giving has increased, he said, and some donors have maintained their membership despite moving to other states. The primary concern he has for remote worshippers is his ability to provide pastoral care for them, something he said suffered during the pandemic.

“You realize how much pastoral care happens at the church door or in passing,” Kinser said. “When you’re not seeing anybody, then not seeing anybody doesn’t tell you anything.”

St. Paul’s has online worshippers from as far away as Florida and Michigan; if they needed a hospital visit or a funeral service conducted, he’d be hard-pressed to serve them. He said denominational networks may become essential for that moving forward, such as when an Episcopal priest in New York asked him recently to deliver communion to a parishioner who had gotten sick while traveling and ended up in a Winston-Salem hospital.

How is your congregation providing care for those attending virtually?

The Rev. Dr. Katie Hays, the lead evangelist at Galileo Church in Fort Worth, Texas, said she has some of those same concerns. Does the church’s budget need a line item so a pastor can fly out of town to conduct a funeral for a member who worshipped online? Should the church prepare ready-made care packages to send to faraway members who are sick or grieving? And what about baptisms?

Hays said she doesn’t yet have answers to those questions but firmly believes that remote worship is the church’s new frontier. She also admits that she was the last holdout at Galileo when it came to offering online worship. She’d seen so many churches do it badly and felt that people already had more than enough screen time, ultimately agreeing to the concept in 2019 largely because she wanted the far-flung LGBTQ community to have ready access to an affirming congregation.

What Galileo quickly discovered was that the platform also appealed to neurodiverse worshippers who might not feel comfortable in crowds, as well as to those with mobility impairments. During the pandemic, the church hired a second pastor devoted to helping virtual worshippers develop a robust online community. Hays refers to the church’s Inside Out online worship experience as the “back pew” of Galileo, the place where those hesitant to come inside can get a taste of the church’s ethos before ever crossing its threshold.

Who can participate in your congregation at a deeper level because of virtual opportunities?

“I feel like I’m 500 years old, like I’m the priest who opposed the printing press. But this new technology came along, destabilizing power from the center,” Hays said.

And even those who are comfortable with in-person worship have appreciated having the option of participating online, she said. A mother with several children recently told Hays she used to have two choices on Sundays: get everyone fed, dressed and over to the church on time for the evening service, or don’t. She now has multiple options: they can come in person or watch together on the couch with a homemade altar for communion, or she can tune in on her own while preparing her family’s Sunday dinner.

As much as she resisted the change, Hays said, her church’s goal has always been to scoop up spiritual refugees who don’t necessarily do traditional church. The changes at Galileo, accelerated in part by the pandemic, have forced her to confront her technological limitations, along with her notions of what worship is supposed to look like. Now, after welcoming in-person worshippers, she looks directly at the camera and thanks her online congregation for inviting her into their homes, something she calls “a tremendous act of trust.”

“It works with your sense of who’s the host and who’s the guest,” she said. “I think so much about how we have to trust people to make their own decisions about how, when and where they’ll participate. It calls on us in the professional clergy to release control of that, and I pray each day to have the grace to trust people.”

She noted that they have a saying at Galileo: You are a grown-ass adult imbued with the spirit of the living Christ.

“Either we believe that or we don’t,” Hays said. “This is really calling our bluff.”

Questions to consider

- How have the expectations that pastors and congregations have for each other changed over the last three years?

- North Canton practices communion weekly. What influence do your congregation’s worship practices have on expectations for in-person attendance?

- What worries you about the shift in patterns of attendance? How can you distinguish your own grief from your analysis of the situation?

- How is the work of supporting the ministries of the church changing? What are the skills and experience needed to offer ministry today?

- What is the ratio of in-person to virtual attendance in your congregation? What questions about the vitality of the virtual congregation are being raised for you?

- How is your congregation providing care for those attending virtually?

- Who can participate in your congregation at a deeper level because of virtual opportunities?