Loving through failure

For a long time, my baseball team held a significant record in professional sports, but it wasn’t a fun one.

My beloved, beleaguered Seattle Mariners did not make it to the playoffs for 21 years — from 2001 to 2022. It was the longest active playoff drought in American professional sports.

And yet the voices of Mariners radio announcers, trips up to the ballpark and echoes of “maybe this year” filled my growing-up years. We cheered on our stars, from Ken Griffey Jr. to Ichiro to Felix Hernandez, without ever seeing them win that much. Blame it on bad management, bad player investments, a cheapskate mentality among Mariners ownership. Google “long-suffering” and you might just see the Mariner Moose mascot trying to hype up a crowd.

Then came 2022 and the walk-off home run that sent us into the postseason for so much longer than we thought we’d be there. After a heartbreaking second-round exit (never talk to me about the Houston Astros), we Washingtonians entered the 2023 season full of the thing we’d hardly dared let stir for all those years: hope.

We missed the playoffs by one game.

Now it’s spring again. Baseball is back, and as of this writing, my Mariners have lost more games than they’ve won. Yes, it’s early, but my family is already having conversations about how much, exactly, we should be giving of our time and energy to this team.

After all, baseball games are long, even with the introduction of the pitch clock and other rule changes designed to make the sport more engaging to a wider audience. And not only are the individual games long; there are 162 games in the regular Major League Baseball season. Your team plays nearly every day from April through September.

We Mariners fans maybe feel a bit spoiled now, having enjoyed the sweet taste of success. So if failure is looking highly likely, why turn on the TV or the radio any more than is necessary to avoid accusations of being a fair weather fan?

Is there a limit to how much you should love something that might be a lost cause?

Yes, I know, baseball is a game. It’s grown men swinging at a ball with a wooden stick. At the same time, it is so much more.

I believe there’s a reason sports metaphors show up so often in sermons, lectures and the like. These silly games teach us something about the human spirit, and following these silly teams can too. In my case, it’s led me to some gnarly questions about what is worth our devotion. Is it OK to follow the losers?

In sports, the definition of losing and winning is straightforward: the winner is whoever has the most points at the end of the fourth quarter, the second half, the ninth inning, regulation time. The fastest time for the racer, the highest leap for the jumper wins the prize. We can check a team’s record and make instant judgments about their chances of success.

Defining “winning” in much of life apart from sports, however, isn’t quite as straightforward. Those of us who follow Jesus inhabit a faith tradition that asks us to look at the normal order of things upside down: the last shall be first, the meek shall inherit the earth, and so on. What we value can be countercultural.

I recently got to sit in on a conversation with the Rev. Dr. Edgardo Colón-Emeric, the dean of Duke Divinity School. In response to a question regarding churches that are struggling or shutting down, he remarked that failure is something that we, as Christians, should not be afraid of, because “failure is at the heart of the Christian story.”

He offered a couple of examples of this confounding heart: the comments made on the Emmaus walk (“we thought he would be the one to deliver Israel”), how the resurrection didn’t take away Jesus’ wounds.

Christianity is not meant to be showy, glamorous, triumphalist. Instead, as Colon-Emeric said, it has a built-in fragility to it, a fragility that is part of our identity. The assumption that a church’s closing means the end of that church’s story is far from true. God is still up to many things.

Can we still hope that churches stay open? Of course. Can I still hope my team can turn things around in time for some meaningful October baseball? I absolutely will. There’s a certain lovely faithfulness in being unafraid that something we love might fail.

Is there a limit to how much you should love something that might be a lost cause?

Shouldn’t we get it by now?

From the inside looking out, we’re aware of the dimming daylight even as we’re typing away, chasing children, on another Zoom. And then we check the time: only 5:15. Whoa.

We’ve observed “spring forward, fall back” our whole lives. We’ve made it through our share of winters. We understand the shortening of days and lengthening of nights. We know how this works. Don’t we?

And yet here we are, year after year, still surprised, still looking outside and saying, “Can you believe how dark it is already?!” (Or, in the words of a TikTok I still think about, “Bro, it’s 5:15! What?”)

When we think of Advent, the themes of darkness, expectation and (im)patient anticipation often come to mind. ’Tis the season to watch and wait. But there’s another element of this time of year that I want to dwell in: the element of surprise.

When we’ve grown up in the church, or even when we’ve simply attended for long enough to know the lyrics and liturgies, the story of Christianity can become a little too familiar. For us and for our salvation he came down from heaven, we may find ourselves droning along each Sunday, focused more on our lunch plans or what remains to be accomplished before Monday’s return. We may grow so accustomed to the mysteries of our faith that we throw around terms like “incarnation” and “ascension” in a way that strips them of any mystical meaning.

But can we back up just a few steps?

[He] was incarnate from the Holy Spirit and the Virgin Mary

and was made truly human.

Think about how you’d “translate” this into normal, everyday language. God chose to be like us, putting on our flesh forever. That’s a crazy, crazy story.

For our sake he was crucified under Pontius Pilate;

he suffered death and was buried.

On the third day he rose again.

No wonder the early Christians got some weird looks (and, well, worse).

“Historically, [Christianity] was a surprise because Christianity was born and emerged and grew in a Roman world that had no expectations for it, didn’t know what it was, and couldn’t have anticipated it,” says C. Kavin Rowe, a New Testament scholar. “Christianity was something that the Roman world had never seen and didn’t even have categories for.

“Christianity was surprising also in its particulars,” he adds. “It introduced patterns of life into the world that caught people by surprise in a good way.”

It’s safe to say that at this point in history, Christianity — at least in the way most people conceive of it — is not much of a surprise. It’s pretty mainstream: no longer a fringe movement. But just dream with me for a second. What if the good news — in all of its particulars — became surprising once more? What if we were as astonished by it as by evening’s early arrival?

Yes, there can be plenty of comfort in familiar rhythms and words, but what might it look like to reclaim some of that wonder — not just for shock value, not just because we’re bored or distracted, but in a way that honors the story we have received?

Maybe it’s as small as reading the passages we know by heart in a new translation for a few days. Maybe it’s looking them up in the Art Search from the Calvin Institute of Christian Worship and seeing some of the creativity those passages inspire. Or maybe it’s simply changing the posture we take when we approach the old, old stories.

How might we be caught off guard?

We joke about the changing seasons surprising us, but the brief days and long nights still startle us each year — “How is it dark already?!” “The sun is already up!”

I hope the jarring reset of our clocks and microwaves and (non-smart) watches might nudge us to do a bit of an internal reset too. I hope the changing church seasons might surprise us as well— that, in some weird and wonderful ways, we might be amazed this Advent by the bizarre, glorious truth of the baby who was God-with-us, the God-man who sits at the right hand of the Father, still wearing his human skin and bearing marks of Roman nails.

I hope we never get used to it.

In the early days of the pandemic, a highlight each day at my house was pulling up John Krasinski’s “Some Good News” as dinnertime viewing. My laptop joined us at the table each evening to provide a few bright spots amid the dire headlines. The stories of COVID patients being discharged from the hospital to cheers and applause, Zoom singalongs with the cast of “Hamilton” — in the spring of 2020, these bits of brightness felt like a lifeline to me.

And I’m not alone: a recent study from psychologists in the U.K. dug deeper into the “why” behind the seemingly obvious phenomenon of the positive effects of good news on our well-being.

The implications of that “why” should spark our imaginations for the way we tell stories about our work in the world. Your ministry might be changing lives in all sorts of ways — but the stories you share about your ministry might be doing that, too.

Research has long confirmed the effects of seeing bad news on our minds and our health. On the one hand, it makes us feel worse — but on the other, thanks to evolution, we’re wired to pay attention to anything that might threaten us.

This particular study, though, looked at the effects of seeing good news stories after bad news stories, as a kind of counteractive antidote.

“The group that was shown negative news stories followed by positive ones fared far better than people who were only shown a negative news story,” writes one of the researchers on the study. “They reported less decline in mood — instead feeling uplifted. They also held more positive views of humanity generally.”

The good news that made the biggest difference for this group? Stories of kindness, of human beings showing up for each other.

The researchers tried out other kinds of positive news, seeing “how people exposed to a negative news story followed by an amusing one (such as swearing parrots, award-winning jokes or hapless American tourists) fared.” But when it came to overall uplifting effects on participants’ mood and hope for humanity, parrots and tourists were no match for acts of kindness — stories “such as acts of heroism, people providing free veterinary care for stray animals, or philanthropy towards unemployed and homeless people.”

The research pointed to several reasons why seeing stories of kindness may help counteract the doom and gloom of the 24-hour news cycle — for example, the writer notes, it can “remind us of our connection with others through shared values” and can act as a kind of “emotional reset button, replacing feelings of cynicism with hope, love and optimism.”

In the conclusion to her news piece on this study, the researcher writes, “Perhaps including more kindness-based content in news coverage could prevent ‘mean world syndrome’ — where people believe the world is more dangerous than it actually is, leading to heightened fear, anxiety and pessimism.”

Of course, the world is incredibly dangerous for many, many people — and positive headlines are no match for the harsh reality some of our neighbors have to face each day. The simple act of reading good news is not, in itself, the way to a better world. I think, though, that the researcher’s article on this particular study intends to critique the way news coverage takes advantage of our threat-detection wiring. The researcher wants to push those working in news media to consider balancing their coverage and including true stories of kindness along with the bad news.

I think, too, that there is a challenge here for all of us who work in Christian institutions, whose job it is to share the good news we’ve been given.

“The Good News Jesus embodied was news. Something to share, to proclaim,” writes Debie Thomas in a piece for The Christian Century provocatively titled “Reclaiming the E word” (the “E,” in this case, being “evangelism”). “We’ve become so adept at articulating who we are not and what we reject. But can we also articulate who we are? What we affirm?” she asks.

Can we share the good news of how we strive to embody the good news?

Of course, we should be thinking about the logistics, the concrete results, the returns on investment, the actual tangible work that we are doing and the difference that we are making. There is something, though, that I don’t want us to lose sight of — the fact that the way we share about our ministries matters, because the effects on the people who see our stories might be greater than we can imagine.

I have the immense privilege and joy of getting to work with various teams here at Leadership Education at Duke Divinity and hear about the impact our grantees and partner organizations are having in the church and the world.

Seeing their inspiring stories, acknowledging the hope they give me, stirs up in me a greater urgency and a heightened awareness of the stakes in my communications work. How can I help get the word out about these incredible ministries, not to boost web traffic, but to help change hearts and lives?

The stories we tell about our ministries matter. We never know who might be listening, watching, hoping for the relief of seeing an act of love on a loveless day.

Here’s what I want to know: How do you share the stories of kindness and care that come out of your ministry? Send me a note — I always enjoy more good news.

A world made out of love: Creation

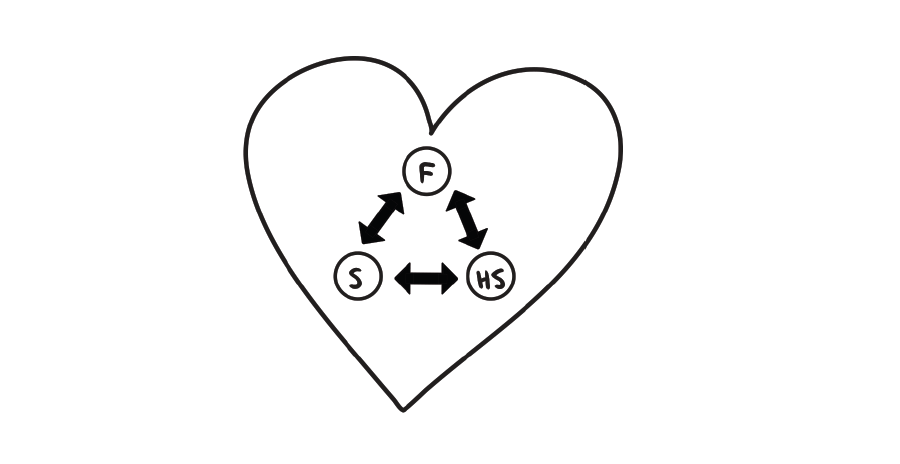

When we talk about the Trinity, we talk about love: the three persons of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit in an ever-moving, ever-giving dance of love.

When we talk about creation, we also talk about love: the love amongst the three persons that spilled out into sun and sea and you and me.

Theology has a couple different terms to talk about these loves and how the Trinity works in relation to itself and in relation to what has been created.

When we think about that dance of love that Father, Son, and Spirit spin and move in, the inner life of these three persons, we are thinking about the immanent Trinity. When we say “immanent,” we mean “internal,” “innate,” “inside.” This is a pretty mysterious concept, because there’s only so much we can know and say about what goes on inside the Godhead apart from what we can see in the world around us.

But we can say a few important things. The apostle John put it neatly in his first letter to some early Christians: “Whoever does not love does not know God, for God is love” (1 John 4:8). God does not simply have love, or give love. Love is not simply an attribute of God; it’s God’s whole being.

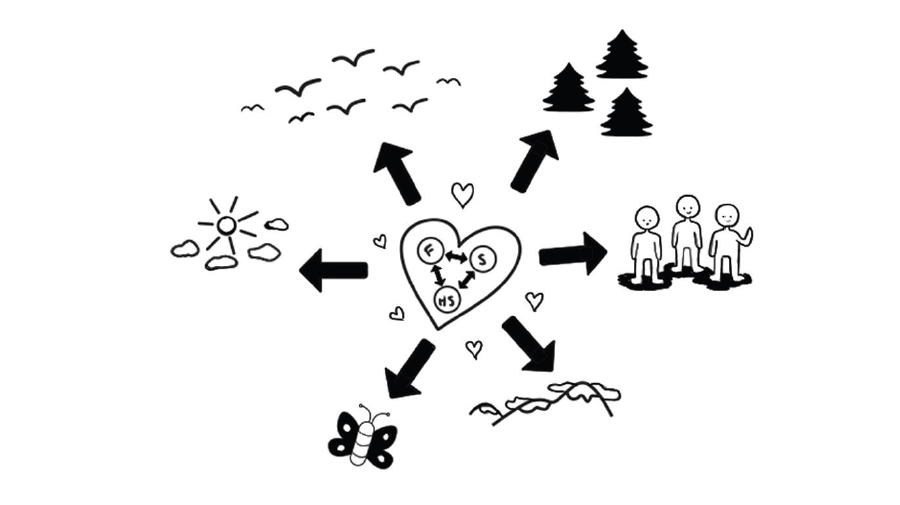

And God chose to allow that love to burst out of God’s very own self.

‘When God began to create the heavens and the earth …’

This is where we begin to see the economic Trinity at play — the Trinity in its relation to what is not God, in relation to what God has created. God could have chosen to just remain as the immanent Trinity forever, having nothing to do with that which is not God. The love flowing freely between the persons of the Trinity would have been enough for God. Father, Son, and Spirit were not sitting around sulky, moping, in need of praise and adoration.

Creation wasn’t necessary.

Our world did not need to exist. Everything we see and smell and taste is excessive: an outpouring of God’s love. God didn’t need to create humans or frogs or planets to satisfy some whim or to appease some lack. God didn’t need us.

But God wanted us.

There’s a phrase attributed to St. Augustine: Amo; volo ut sis. Translated from Latin, it reads: “I love you; I want you to be.” Imagine, for a moment, God whispering this as the heavens and the earth began to take their shape, as Adam was formed from the dust and breathed into life. “I love you; I want you to be.”

God needs nothing — but God wants us to be. And in creation, God wanted to share the love that is God’s own self and being. In creating, the love within the Trinity flooded over into every nook and cranny of the cosmos, every inch drenched in it.

‘… the earth was complete chaos, and darkness covered the face of the deep …’

So God didn’t need to create, but God chose to, freely. That’s a statement we need to make when we talk about creation. There’s another piece to it, though: that God created out of nothing.

When we humans “create,” we use paints, bricks, computers, thoughts in our minds: things that already exist. When God created (in the truest sense of that word), God used … nothing.

The term theologians use to describe this concept is (you guessed it) a Latin phrase, creatio ex nihilo, which translates to “creation out of nothing.” This sets God apart from any one of us, and it sets God far beyond the reaches of any technology or tool we might develop. Only God can take nothing — a void of voids — and create.

The scholar Janet Soskice puts it like this: “Creatio ex nihilo affirms that God, from no compulsion or necessity, created the world out of nothing — really nothing — no preexistent matter, space, or time.” This concept of “really nothing” is essentially impossible for us to fathom. How can we imagine this kind of emptiness? What creatio ex nihilo does is force us to confess just how transcendent, just how “other,” God is.

But it also shows us another key thing about God.

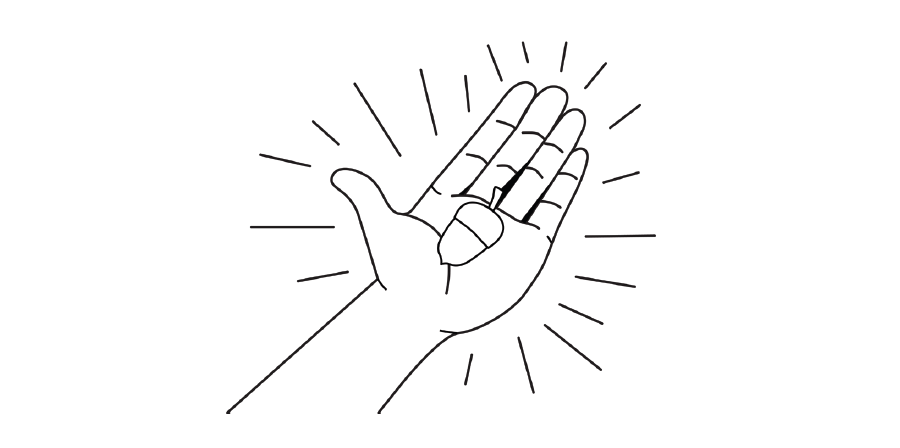

Many centuries ago, in an English town called Norwich, a woman lived inside a church.

The woman, who became known as Julian of Norwich, lived the life of an “anchoress,” voluntarily secluding herself in a cell within the church walls so she could devote herself to prayer and worship.

She spent many years there, sifting through and making sense of some remarkable things that had happened to her. She wrote a book, “Revelations of Divine Love”— the first book written by a woman in the English language — about a series of “showings” she had received from God during a severe illness. These showings were often dramatic and graphic, showing the suffering Christ in vivid detail, but one of them included a simple image.

And in this vision he also showed a little thing, the size of a hazelnut, lying in the palm of my hand, and it was as round as a ball, as it seemed to me. I looked at it and thought, “What can this be?” And the answer came to me in a general way, like this, “It is all that is made.” I wondered how it could last, for it seemed to me so small that it might have disintegrated suddenly into nothingness. And I was answered in my understanding, “It lasts, and always will, because God loves it; and in the same way everything has its being through the love of God.”

God is transcendent and “other,” yes. But God also knows us and sustains us in a profound and personal way. This is not a watchmaker God that some philosophers have spoken of: a God who puts together a watch and then steps back to let it tick away. God is not aloof. We last because God loves us. We couldn’t exist without that love — the enveloping love of a God who is both utterly beyond us and beside us.

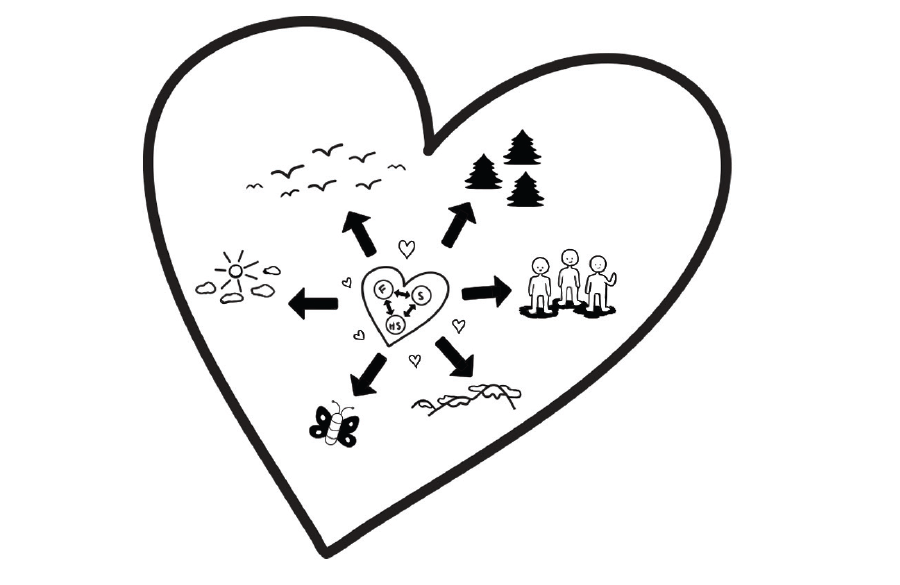

To emphasize that God sustains us and all of creation, theologians often reference the idea of creatio continua, another fancy Latin phrase that means that God constantly upholds all of creation.

God did not simply, at one time, desire to create the world. God always wants the world; he consistently calls what he made “good.” God actively re-creates the world in every single moment. God always wants us, and everything, to be.

What happens when we start to forget some of these ideas about creation?

Much of Christian theology ends up being centered around the person and work of Jesus Christ — which makes sense, considering the name “Christian.” The attention we give him is well-deserved, after all. But sometimes the way that focus plays out results in some long-term damage — like when the doctrine of creation starts getting squashed.

A weak theology of creation is bad news for creation. If we focus so much of our energy on ourselves as humans, on what God has done for us, and we don’t pay much attention to the rest of the universe that God made, we end up staring at a tiny piece of the big picture that is God’s love and care for the world.

A Native American theologian named George Tinker knows this all too well. He writes about the ways Christian missionaries preached the gospel to Native Americans, giving it the usual Western-church spin of humanity’s fall from grace, their sinful nature, and their need for redemption. For traditionally oppressed and marginalized peoples, however, the emphasis on humanity’s sin and their need for a savior doesn’t sound like the best news. “Unfortunately,” Tinker writes, “by the time the preacher gets to the ‘good news’ of the gospel, people are so bogged down … in [their] internalization of brokenness and lack of self-worth that too often they never quite hear the proclamation of ‘good news’ in any actualized, existential sense.”

Tinker calls for us to start sharing the good news from, well, the beginning of it all: that first “in the beginning.” He asks for us to “take creation seriously as the starting point for theology rather than treat it merely as an add-on to concerns for justice and peace.”

When we begin to neglect the significance of creation — what it says about God and God’s love — we can find ourselves getting so wrapped up in our own lost-ness and need that we forget just how loved we have always been, just how valuable everything and everyone around us is. When our theology becomes centered on “just Jesus and me,” our sisters and brothers — our whole planet — suffers.

What might it look like to take creation seriously, then — to remember how God holds us tight and close, wanting us to be?

What might it look like to remember that we live in a world that God wants?

God’s creation is vast and expansive. God does not choose to be God only for God’s own self — God is the One who delights in extending love and life to others. God’s good world — created and sustained by God’s loving-kindness — is worth knowing and celebrating and protecting.

Luckily for us, God chooses to reveal to us more of what we, creation, and God are like. That’s what we’ll look at in the next chapter.

From “Napkin Theology,” by Emily Lund and Tyler Hansen. Copyright © 2023 by Emily Lund and Tyler Hansen. Excerpted by permission of Wipf and Stock Publishers. All rights reserved.