‘Here for you, not because of you’ — Nashville nonprofit serves up coffee, soap and empowerment

Don’t be misled by the makeshift counter and tent outside Humphreys Street Coffee Shop in Nashville, Tennessee. The business is here to stay.

That renovated green house is a symbol of permanence, commitment and determination. After all, helping people understand their value is not quick work.

As a social enterprise of Harvest Hands Community Development Corporation, the coffee shop serves up more than cold brew and lattes; it provides jobs, mentorship, discipleship and skills for teens from the community nearby.

“We don’t hire students to make coffee,” Harvest Hands executive director Brian Hicks likes to say. “We make coffee to hire students.”

On a hot, humid August afternoon, local residents pull up or stroll over in a steady stream. One speaks of how he likes both the coffee and the aesthetic. On the edge of a recently gentrified neighborhood, it’s charming, inviting. And powerful.

In a non-COVID season, Harvest Hands has met community requests for after-school activities, sports leagues, leadership training and more. Founded in 2007 by Hicks and his wife, Courtney, the organization has grown from a neighborhood gathering of a dozen or so kids to a nonprofit that brings in $500,000 a year in coffee roasting, brewed coffee and handmade soaps, in addition to gifts from individuals, churches and foundations.

Does your organization have empty spaces that could be re-imagined into a way to serve your community in this season?

There are typically 10 full-time staff and up to 50 more in various part-time roles — including those students. In the wake of COVID-19, the shop is currently curbside and delivery only.

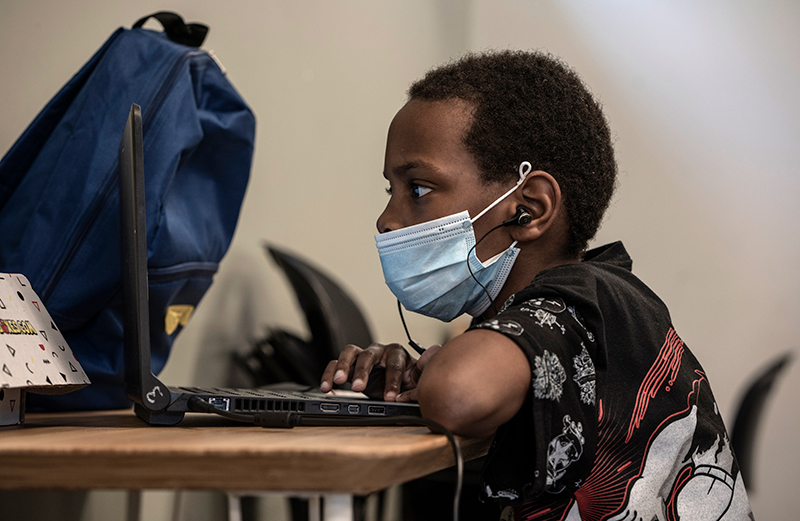

After-school programs are shuttered for now, coffee and soap production continues with just a handful of students, and the once-bustling community center has transitioned to a quiet, safe and internet-ready space for younger children to take part in remote learning.

But the undercurrent of digging in for the long haul remains.

“Numbers are important,” said William Parker, the Harvest Hands director of youth and mentoring. “But they don’t dictate success.”

‘What do you love about your neighborhood?’

It was the Rev. Howard Olds who drew Hicks from Kentucky to the neighborhood. Olds was the longtime pastor of Brentwood United Methodist Church, an affluent congregation in an adjacent county. He was interested in neighborhood revitalization in South Nashville, not far from downtown; the church had the resources but not the manpower for the work.

Hicks, a seminary grad who cut his social activism teeth working in inner-city Philadelphia, Chicago’s South Side and Louisville, was hired by the church to lead the nonprofit. As the organization grew, all other staff would be funded through Harvest Hands and represent a variety of denominations, experience and education.

Hicks had been further inspired by the writings of John Perkins, co-founder of the Christian Community Development Association, and was ready to see communities empowered through true partnership rather than charity. He was ready to put down roots.

Olds, meanwhile, had attended a community meeting and was told that if he really wanted to make a difference, the church should buy the drug house on the top of a neighborhood hill.

Traditioned Innovation Award Winner

Leadership Education at Duke Divinity recognizes institutions that act creatively in the face of challenges while remaining faithful to their mission and convictions. Winners received $10,000 to continue their work.

“So they did,” Hicks said. “He didn’t ask the congregation, which was made up of CEOs and leaders. He told them. And that became the entry point.”

The house was torn down, and a fall harvest festival was held on the lot.

“The price of admission was a survey,” Hicks said. “We asked them, ‘What do you love about your neighborhood? And what would you change?’”

The residents were concerned about kids with nothing to do but get in trouble. An after-school program was a simple ask.

The newly formed Harvest Hands bought a small house and started working with children in 2008. It had outgrown that house by the following year, and the Methodist Church donated the building — the former Humphreys Street UMC — that would eventually become the coffee house. But things were just getting started.

Ruben Torres, an introverted middle schooler who would hunch over and fold into himself as if he didn’t exist, was already part of the Harvest Hands program. Hicks saw promise in Torres and asked whether he might be interested in a new opportunity.

He could learn how to roast coffee, “a grown-up, adult thing that was super exciting,” Torres said. Harvest Hands was looking for a social enterprise that would engage teens; a paycheck would be a definite draw.

Whom do you need to invite to get involved in your community’s mission in a new way?

The church provided an introduction to one member in particular: Cal Turner Jr., former chairman and CEO of Dollar General. Hicks asked Turner for not only a Diedrich coffee roaster — a high-quality machine geared toward specialty batch roasting — but also a trip to the company’s Idaho headquarters for himself and one other to learn how to use it.

“That’s like learning to drive from Henry Ford,” Hicks said. Turner told the then-30-year-old Hicks to write a business plan and he’d make it happen. Hicks enlisted the help of the teens. After a few tweaks here and there, Turner held true to his word.

Torres was chosen for the trip. Today, he’s production manager and head roaster, overseeing teens not unlike who he once was. Harvest Hands, he said, helped him learn about his value as a person.

“Something we very much believe in is that everybody in the community has the potential to be greater,” Torres said. “There are also people who have the potential to be leaders. The talent is there. There’s no need to bring a whole bunch of external factors.”

It is easy to default to bringing in trusted external experts to start something new. What potential is already present in your community waiting to be invited to contribute?

He considers himself fortunate to have had an “awesome support system and great parents.” His mother, Jael Fuentes, is now soap production manager at Harvest Hands. But Torres also understands he’s in a position to model change, leadership and motivation for others. His own experience lends credibility.

“They take things to heart from me,” he said. “As opposed to saying, ‘You don’t know my life.’”

Giving it back to the people

As coffee and soap production grew, the Wedgewood-Houston neighborhood began to gentrify.

“The first thing we did,” Torres said, “was to invite the community members in and say, ‘What do you need? What do you see?’”

With housing costs rapidly rising, many were being forced out.

By 2015, Harvest Hands staff knew they needed to relocate. They met with members of the Napier-Sudekum neighborhood, less than a mile away, and learned of the need for after-school programs there, too.

Naturally, there were new challenges. Napier-Sudekum has more than 800 government housing units; crime rates and violence are high, and Harvest Hands notes that the average annual household income is $6,500. But it is also a community in which neighbors look out for each other and untapped talent is overflowing. Hicks found an old warehouse perfect for a community center and set to work.

“It was the craziest thing,” he said. “We beat the realtors and the developers to the building. As much as gentrification pushed people out, it drove up the price of that original crack house lot [in Wedgewood-Houston].”

The property that Harvest Hands had bought for $275,000 was sold to developers for $2.3 million, with plans to add shipping container units for “affordable” housing. The funds from the sale have been given back to the people, in essence, as Harvest Hands continues to expand its reach.

“It’s creatively using gentrification for justice,” Hicks said.

A call to reform

The bright and spacious community center in Napier-Sudekum officially opened in 2016. Named for Olds, who died in 2008, it is adorned with colorful murals and words like “integrity,” “compassion,” “love,” “courage,” “respect” and “wisdom.” There’s a playground and a large lab-like room that now houses two coffee roasters, stacked bags of coffee beans and packaged handmade soaps.

What do the spaces your organization inhabits communicate to others? How do you cultivate a space in which people feel valued?

As one of the first craft roasters in Nashville, Harvest Hands had steadily built a following that has helped sustain the organization through the pandemic. Online sales through its website include coffee from Africa, Central America, South America and Southeast Asia, in addition to liquid and bar soaps, laundry soap and a coffee sugar scrub. The brick-and-mortar coffee shop on Humphreys Street opened in 2018.

When people visit the Howard Olds Community Center, Hicks said, they often seem surprised at just how “amazing” it is. “Several things go through my mind — first, do you think these kids should not have a great space? Is it supposed to be a dump? We try to help kids believe that they are valuable and they are worth it.”

Jessica Holman, the organization’s senior director of employee and community relations, grew up in the area and came to work at Harvest Hands while in graduate school at Vanderbilt University close to a decade ago. She knows firsthand that local residents have “inherent talents and skills,” she said. “They just need opportunities to let them shine.”

“I wish that people knew the people in these communities,” she said. “There are some amazing people here. Intelligent. Creative. And I wish people knew about the sense of community here, too.”

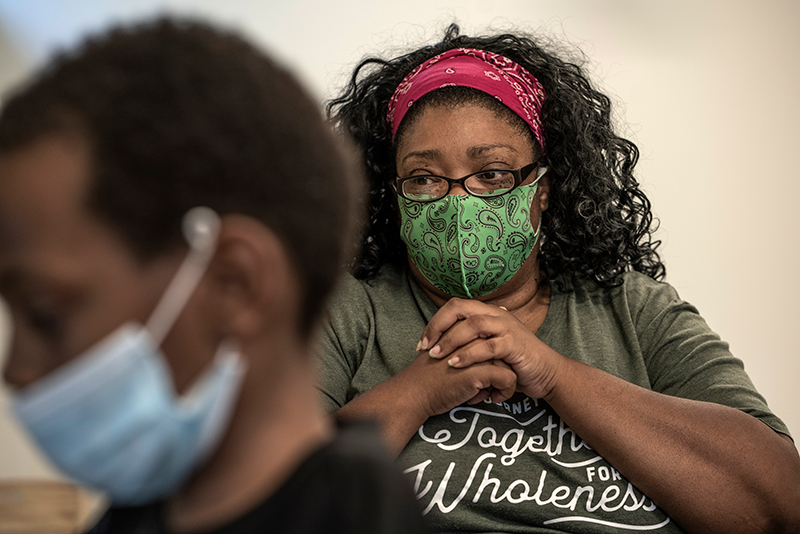

Consider Jarica Sanders, a self-employed artist, hair braider and mother of three. Her kids, ages 7, 8 and 10, have taken part in Harvest Hands programs for several years. They’ve played a variety of sports with the organization, participated in after-school programs, learned life skills, been encouraged in their faith and are now going to the community center for virtual learning. Sanders is hoping her oldest son, Lemy, will be able to gain work experience through Harvest Hands when he’s older, too.

In her Napier-Sudekum neighborhood, she said, “if you don’t know about Harvest Hands, I don’t know where you’ve been.” And it’s not just the activities and opportunities for the kids. Sanders said the organization has a reputation for truly partnering with residents.

“We have parent meetings at Harvest Hands,” she said. “They give us the chance to come in and tell them what’s working and what’s not working and what they could do better. They get the community involved, and I really like that. A lot of programs, they just come out and say, ‘We have this, this and this.’ But the people at Harvest Hands actually take the time to say, ‘What do you need? What do you think can we add?’ That’s a very big help.”

Harvest Hands follows the tenets of asset-based community development, which include focusing on those strengths, gifts and talents already present rather than just working to “fix” what’s wrong.

How much of your organization’s work is “fixing” what is wrong, and how much is building upon the strengths, gifts and talents already at work?

Parker, a Memphis minister who came to Harvest Hands in January, said those concepts had always been part of his story; he just didn’t know them by that name.

Learning about the powers that systemically oppress communities — especially communities of color in urban environments — tugged at his heart. So did the opportunity to continue his work with teens.

“It’s not enough for me to just believe that Jesus Christ has changed the world through his actions,” he said. “That same spirit that is in Jesus is in me, and it’s calling me to bring reform, to change, to be with the community and say that it doesn’t have to be this way. The gospel is more than just the theological ideology that we hold that sounds good on Sunday mornings. It calls for social reform to be in the mix.

“I’m just trying to lean into that social holiness piece and say, ‘OK, justice is really close to the heart of God.’ If I want to be able to understand how faith is played out in communities, I need to be in a position to hear stories and say, ‘Where is God in that story, do you think?’ … What drew me to Harvest Hands was to have space to ask the big questions without attempting to fix anything. That’s where real healing takes place, where people are brought back to themselves.”

Living Jesus out loud

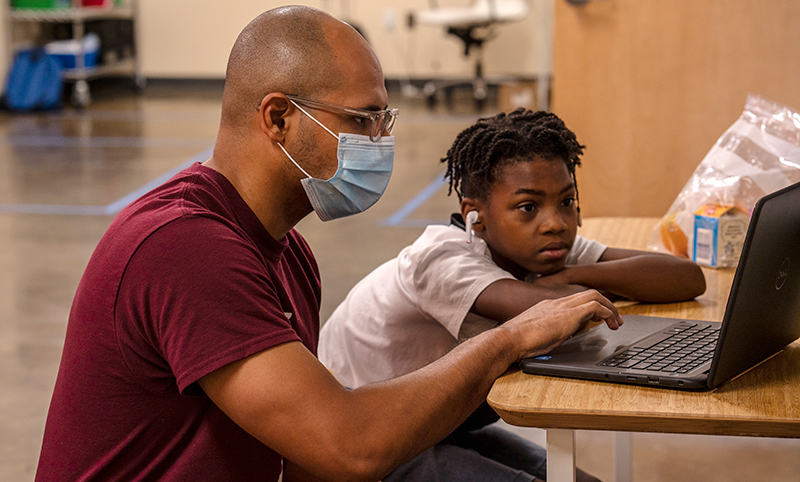

That same hot day that customers were lining up for coffee at the shop, Parker was sharing a classroom in the community center with a middle schooler taking part in remote learning; the city’s schools had not yet opened for in-person classes because of COVID-19.

Across the hall, Chartrice Crowley, the director of elementary programs, had a handful of younger students of her own. The kids have been on alternating days from 7:30 a.m. to 1 p.m., mindful of social distancing limits, with sibling schedules matched to ease the burden for parents.

This effort, too, came from going to the community and asking rather than assuming what was needed. It is the difference in saying, “We are here for you, not because of you,” Parker said.

How might your organization’s work be different if it existed “for” people rather than “because of” people?

In more normal seasons, Crowley plans after-school enrichment opportunities like African drumming and ballet, homework time, personal development, fun, and a faith component. Harvest Hands allows her to “live Jesus out loud” in a way that working in a public school would not.

“The thing that makes me most proud about working here is that I get to see the fruits of the seeds that have been planted,” Crowley said. “I get to see greatness every day. These kids are amazing. They’re fun. They’re witty. They’re smart. They blow me away every day with what they know.” Even when they’re figuring out learning through a screen.

There’s a cultural element to Harvest Hands, too, one that opens doors of opportunity, knowledge and respect for the predominantly Black community. Classrooms, for example, are named for historically Black colleges and universities, with those names changing each semester to increase exposure.

“Students are placed in their ‘house’ at the beginning of each semester,” Holman said, “and they participate in house games throughout the semester, where they are able to win prizes. We think it’s important for our students to know the history of HBCUs, why they were created, and that they are an option for them to further their education. It’s important that they learn about Black excellence at an early age so that they grow up learning that greatness lies within them.”

Local street artist Charles Key serves as another inspiration; his work can be seen throughout the community center (as well as at various Nashville sites). There are portraits of lesser-known Black leaders — many of them from the area — on the walls of the middle school classroom.

Overall, the ongoing uncertainty of COVID-19 makes some aspects of the future unclear. What is clear is that Harvest Hands will keep asking the community what it needs and endeavoring to incorporate the resources available to bring it about.

Torres hopes to develop a roasting certification program for the students he oversees. Hicks is looking forward to hallways full of kids once again. Parker is exploring pathways to success for high schoolers. And Holman will keep seeking opportunities to tell the story of long-term vision and sustainable success.

As for others hoping to do the same? Holman suggests that they’d do well to check their “why.”

“Will you be there for the long haul, willing to relinquish power to the people within the community and let them shape it?” she said. “Our goal, at the end of the day, is to work ourselves out of a job. If we’re doing what we aspire to do, that means the community will lead. Then they’ll be the ones out there doing what needs to be done.”

Questions to consider

Questions to consider

- Does your organization have empty spaces that could be re-imagined into a way to serve your community in this season?

- Whom do you need to invite to get involved in your community’s mission in a new way?

- It is easy to default to bringing in trusted external experts to start something new. What potential is already present in your community waiting to be invited to contribute?

- What do the spaces your organization inhabits communicate to others? How do you cultivate a space in which people feel valued?

- How much of your organization’s work is “fixing” what is wrong, and how much is building upon the strengths, gifts and talents already at work?

- How might your organization’s work be different if it existed “for” people rather than “because of” people?