Race, healing and changing the world

Our generation is being confronted yet again with the chronic racial sickness of our world. It is good and right for disciples of Christ to do what we can to heal the world of this sickness. At the same time, as a national discipleship leader, my concerns go deeper. I am concerned for Jesus followers not only to bring racial healing to the world and its systems but also to experience deep inner healing themselves. The two are connected.

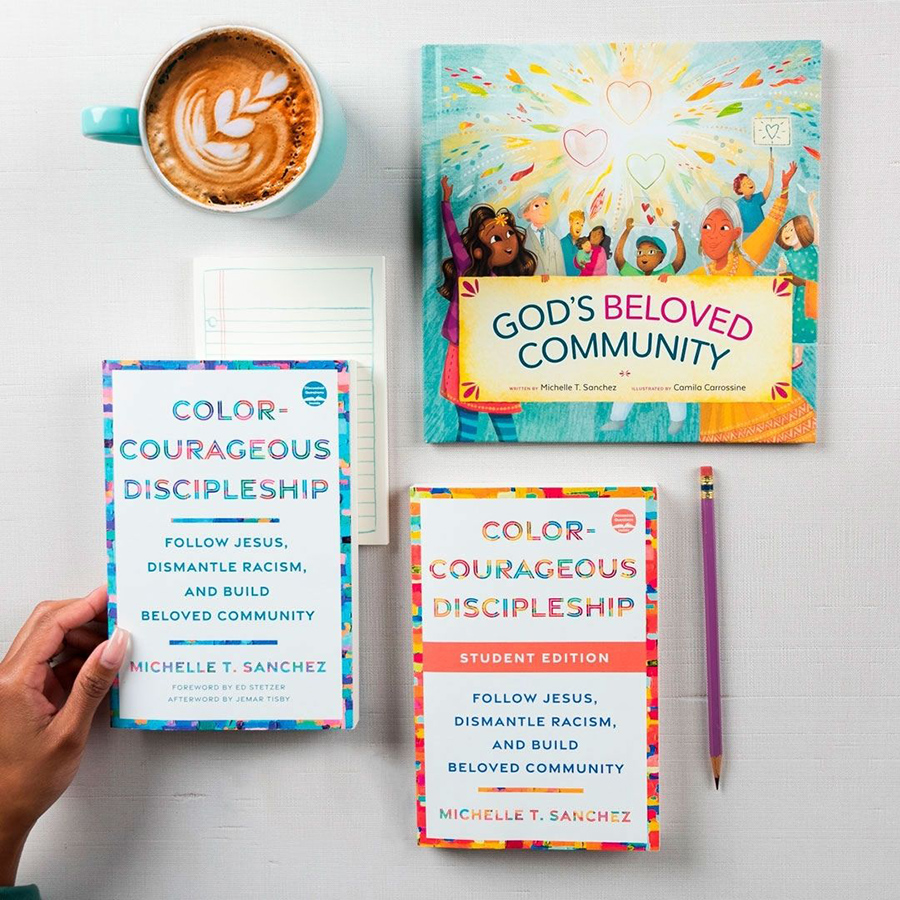

In recent years, I have devoted myself to writing “Color-Courageous Discipleship,” a trilogy of age-tailored books for empowering disciples to make fresh connections between following Jesus and dismantling racism. In the process of writing — and especially while conducting interviews with multiple anti-racist disciples — I have discovered how healing, discipleship and mission are intimately intertwined in a traumatized world. Even now, Jesus is seeking to bring about in you the kind of Spirit-filled inner transformation you need to transform the world in God’s way.

Consider this: the miracles that Jesus performed were always signs and pointers to subtler, yet more significant, miracles. Take, for example, Jesus’ healing of a paralyzed man (Mark 2:1-12). When the man was brought to him, Jesus did speak words of healing — but certainly not the words we might expect. “Son, your sins are forgiven,” he said (Mark 2:5 NIV). This is a curious thing. Instead of responding to the clear and obvious request for physical healing, Jesus perplexed everyone by first talking of spiritual healing. Might he be speaking a similar word to us?

When it comes to race, our world has been deeply traumatized. The word “trauma” comes from the Greek for “wound” and can be used to refer to the wide array of spiritual, emotional and relational wounds that racism has caused. As we seek to dismantle systemic racism, we need to understand the trauma that we are dealing with on a massive scale. Even more, to become true agents of racial healing, we would do well to name our own wounds and seek healing for ourselves as we pursue the healing of the world.

There is a dizzying array of traumas that racism can inflict — both on people of color and on people who identify as white, as Sheila Wise Rowe outlines in “Healing Racial Trauma.” Let’s start with people of color and first acknowledge that people of color have not all been affected by racism in the same ways. As a Black woman, I recognize that there are some forms of racial trauma I can personally relate to and others I can’t. Yet all anti-racist disciples know that when we are aware of the varieties of racial trauma, we can better facilitate lasting healing in diverse communities.

We must open our eyes to how people of color have experienced racial trauma on multiple levels: individual (personal, vicarious, internalized); corporate (historical, transgenerational/epigenetic, environmental); and even divine (raising faith-shaking questions about God). When racial trauma in people of color is not named and addressed, it can produce a variety of damaging effects, including spiritual toxins such as bitterness, apathy, rage and despair.

Yet here is a surprising fact: racial trauma also comes in white. Trauma affects perpetrators too. God created humanity to thrive as a community of equals. So when God’s design for equality is distorted, the perpetrator must also pay an existential price. Today, psychologists call this phenomenon “perpetrator trauma,” or perpetration-induced traumatic stress (PITS).

Just as we recognize that all people of color have not experienced racism in the same way, we would be wise not to make blanket statements about “all white people.” That being said, if we were to understand white Americans as another traumatized group, we might more sympathetically recognize in them symptoms of trauma. We might gain insight into certain reactions that white communities often have when confronted about racial inequity: shock, denial, avoidance, delusion, guilt, shame and more. These are trauma responses, and they point to unresolved and possibly unidentified wounds.

As Resmaa Menakem explains in “My Grandmother’s Hands,” the trauma of racism “has resulted in large numbers of Americans who are white, racist, and proud to be both; an even larger number who are white, racist, and in reflexive denial about it; and another large number who are white, progressive, and ashamed of their whiteness. All of these are forms of immaturity; all can be trauma responses; all harm African Americans and white Americans.”

Faithful anti-racist disciples recognize that we all need healing from the trauma that racism has caused. We all need God’s healing touch. And as we experience healing, we can more effectively become agents of healing to our world in embodying supernatural, Christlike characteristics such as love, serenity, forgiveness, gentleness and grace.

Without the character of Christ, we will be far less capable of bringing lasting healing and reconciliation to the world. This is precisely what the great faith-based anti-racist leaders have understood. As Martin Luther King Jr. taught in “Strength to Love”: “Forced to live with these shameful conditions, we are tempted to become bitter and to retaliate with a corresponding hate. But if this happens, the new order we seek will be little more than a duplicate of the old order. We must in strength and humility meet hate with love.”

When apartheid finally fell in South Africa, many predicted that the country would descend into chaos. South Africans of color finally had their opportunity for revenge. But to everyone’s surprise, chaos didn’t happen — thanks largely to the faith-filled leadership of Desmond Tutu. Through the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Tutu reached out to both victims and victimizers. First and foundationally, he urged victimizers to confess, apologize and make restitution. Yet he also inspired victims to experience the freedom and joy that can come only by yielding to forgiveness, redemption and reconciliation.

Tutu understood that there was no other way for the nation to move forward together. In his words, there simply can be no future without forgiveness. Our best future emerges as we embrace the holistic healing that Jesus offers to each and every one of us. The mission of God has always been as wide as the whole world and as intimate as each individual soul.

The vicious cycle of racial trauma has repeated itself throughout human history, with evil all too often giving birth to more evil. As Miroslav Volf put it: “People often find themselves sucked into a long history of wrongdoing in which yesterday’s victims are today’s perpetrators and today’s perpetrators tomorrow’s victims.”

But we can put a stop to the cycle.

As we pursue healing in Christ, we are liberated, not to be overcome by evil, but to overcome evil with good (Romans 12:21). The more we pursue this healing, the more deeply we will understand the many ways in which healing is an integral part of our journey toward true and lasting beloved community.

Excerpt adapted and expanded from “Color-Courageous Discipleship: Follow Jesus, Dismantle Racism and Build Beloved Community,” by Michelle T. Sanchez. Copyright © 2022 by Michelle T. Sanchez. Published by WaterBrook, an imprint of Penguin Random House. Used with permission.

Christianity is not the white man’s religion. A tradition of Christian faith and practice emerged from the underside of America, from enslaved Africans in the antebellum South. There were no steeples, stoles, or stained glass. This tradition had no such luxuries. The Christianity of enslaved Africans was not a religion of privilege and position. It was a religion of freedom and revolution. Deep in the wilderness of the plantation slavocracy, enslaved Africans would escape to practice a communal spirituality that challenged them to love their bodies and their heritage, and to refuse any conditions that said otherwise. Welcome to the hush harbors, the invisible gathering places where enslaved Africans met to praise the God of the oppressed, pay attention to one another’s needs, and plot the abolition of slaveholding Christianity and the plantation economy. Hush harbors are a place to turn to refashion for our times a Christian community shaped by risky love.

The Terror of the Plantation Economy

The environment of chattel slavery was no walk in the park. Cultural artifacts like the film Birth of a Nation depict Africans as happy with being slaves. Such propaganda numbed and concealed what really took place in the plantation economy. Africans in America were legally and politically considered not fully human. They had no rights that white people were expected to respect and uphold. Any deference given to Black people was out of respect for them as the property of a white master. Black people were legally denied access to the kinds of privileges that uplifted and bettered white people, like government programs, economic self-determination, and voting. Without the honor of human dignity and any rights to ensure their well-being, as property of the plantation economy, enslaved Africans were treated for how they could meet white pleasures. Rape, forced “breeding,” mutilation through beatings, and lynching were only some of the violent bodily tactics white people used to punish and control enslaved Africans. Even the mundane parts of enslaved Africans’ lives were not respected. Enslaved Africans were forbidden to gather or assemble together except under the supervision of white folks. They had curfews to prevent their escape at night. Their leisure was policed to control as much of their time for work on the plantation and to ensure the leisure of the white master and his family. Even the term plantation does not do justice to the racialized economic exploitation Black people faced. Author Nikole Hannah-Jones in her book 1619 calls these Southern sites of oppression “labor camps.” The terror of the plantation economy was a totalizing vision. Every part of the lives of enslaved Africans was expected to be under the gaze of white supremacist, patriarchal capitalism.

Theology and Worship on the Plantation

What enables a race of people to exploit the labor of another race? To see them as their property? To colonize the land of Natives and the consciousness of Africans? What must a people believe about themselves to enact terror on another people and on the planet? “Slaves, obey your earthly masters in everything … , with reverence for the Lord” (Col. 3:22). These words summarize the theology of slaveholding Christianity. And from these few words emerged an entire culture and history of violent desecration of land and peoples. Enslaved Africans had regular opportunities to worship on the plantation in racially integrated churches led by white folks. These integrated plantation churches operated by a separate and unequal rule: Black people and white people sat in the same sanctuaries, but everything else about the worship experience was separated by race, from using different restrooms to separate seating, prayer and Communion rituals, and burial grounds and baptismal waters. Enslaved Africans could also attend segregated gatherings led by Black preachers under the supervision of a white minister and white religious customs. Worship in both of these plantation churches accommodated the terror of the plantation economy and slaveholding Christianity.

The theology of the plantation said that God works through white men to bring the world into order and submission. Most white plantation owners used Christianity, especially the words of Paul, to make Africans docile and numb to their plight, to believe it was God’s will for them to be slaves. Other white plantation owners forbade the enslaved to be taught Christianity because they were worried biblical themes would incite revolution. How can Christianity hold within it these two contradictory possibilities? Race was the theological myth used by wealthy, white, male plantation owners to uphold the chattel slavery economy with a whitewashed, domesticated, heretical Christianity. Only a small percentage of wealthy, white, male plantation owners were actually at the top of the caste. When the owner was not around to be in charge of the plantation economy, wealthy white women were in control. When the owner’s wife was not there, either a poor white man or woman or an enslaved Black man was in charge. Black women and children were always at the bottom. All Black lives were disposable. Race is a powerful myth because the racial caste system has never been consistent. Myths are only as true as people give credence to them and as they function to maintain the status quo. From the beginning of the chattel experiment, poor and working-class white people have shared more in common with Black and Native people than with the white elite. The power of the slavocracy system was that it operated at the intersection of white supremacy, white patriarchy, racialized capitalism, and the theological heresy of slaveholding Christianity.

Hush Harbors and the Plantation

Even if only temporarily, enslaved Africans escaped the plantation economy and slaveholding Christianity by organizing hush harbors. Drawing especially from documented slave narratives, hush harbors have been a treasure trove of study for religion scholars and theologians. The literature on hush harbors has centered two rich debates. First, there is the debate of erasure versus retention of African cultures or Africanisms. Much of the early literature about the period of slavery in the US claimed that the psychic and bodily trauma of the Middle Passage — of Africans being violently forced from their homelands in Africa by European settler-terrorists on ships under the most inhumane of conditions — stripped the first generation of enslaved Africans of much if not all of their memories of their African cultures and customs. Certainly, this cultural knowledge was not passed down to successive generations, the argument went. This psychological and cultural violence was strategic in making African peoples more susceptible to being chattel for white plantation owners. Other scholars contended that hush harbors provided evidence to oppose the erasure thesis. Hush harbors depicted a rich continuity of Africanisms — music, language, religion, stories, and more — that enslaved Africans disguised for their own safety when under white surveillance. Because of the need to disguise Africanisms, the unaware observer could not readily see how enslaved Africans did in fact retain a variety of African customs and practices.

The second debate is over the nature of the Christianity that enslaved Africans practiced. Did enslaved Africans practice the Christianity of the slaveholder, which accommodated their own oppression? Christianity was an empire religion that accommodated the status quo. For enslaved Africans, to accept Christianity was to accept their plight on earth as they awaited their true freedom in the afterlife. Again, by peering into hush harbors, this thesis has been contested. Through the testimonies of enslaved Africans themselves, scholars discovered that Africans in the Americas not only practiced an otherworldly Christian religion that accommodated their oppression; hush harbors that enslaved Africans organized were sites of protest against the dominant Christianity of the slaveholder. In hush harbors, enslaved Africans made plans for permanent escape to the northern parts of the US. Additionally, enslaved Africans carried a hush harbor mindset of freedom with them onto the plantation to both cope with daily terror and plot for abolition without being caught by white plantation owners. This mystical hush harbor was as much a site of interior protest as the material hush harbor was a site of physical protest. These protest actions and mindsets were rooted in particular Christian beliefs that enslaved Africans initially discovered from slaveholding Christianity and then reinterpreted toward revolutionary ends.

These debates have unearthed a rich legacy of the genius of enslaved Africans’ beliefs and practices. In recent times, however, Black prophetic leaders have grappled with the importance of hush harbors not only for their historical relevance but also as a site of contemporary reflection on a more radical model of church and activism.

From “Buried Seeds,” by Alexia Salvatierra and Brandon Wrencher, ©2022. Used by permission of Baker Academic.

The 12th-century philosopher Moses Maimonides writes in his “Mishneh Torah” that the work of restorative justice begins with the public confession of harm. The challenge of naming and owning harm is one that pastors regularly face when repairing relationships within their congregations.

But the stakes of such mediation are much higher when harm is embedded in the church itself. How do pastors and lay leaders navigate the work of repair when the history of their own church is implicated?

We’re a pastor (Lauren) and a sociologist (Gerardo) who, respectively, have participated in and witnessed this difficult journey of reparation at Highland Baptist Church in Louisville, Kentucky. Gerardo watched this process unfold over the past year while on sabbatical, and Lauren has been involved with the process as an associate pastor at Highland.

In 2018, Highland was faced with a shocking discovery. In front of a citywide crowd at a racial justice gathering, a recently retired pastor reflected on the stained-glass windows of his former parish. He marveled that the windows showcased two enslavers, James Boyce and Richard Furman, and one radical segregationist, E.Y. Mullins. Even more, the church’s painted fellowship hall windows portrayed an additional enslaver, Basil Manly Jr.

Congregants in the room that day perked up at the mention of their church, only to realize that their former pastor had just publicly said something they had not known. They learned that their beautiful windows commemorated leaders committed to racist ideals.

Not only was the news startling — a true revelation to the current congregants and pastors — but it also conflicted with the church’s understanding of itself and its ongoing anti-racism efforts.

News of the windows and the enshrined enslavers spread quickly. Members asked questions, wanting to find out specifically which people in which windows owned slaves and when the windows were installed.

They found that the stained-glass windows in the sanctuary were installed in the early 1970s, and the fellowship hall windows were painted even more recently, in the mid-1990s — not at all in the distant past. How could this be? As the buzz about the windows gained momentum, the church’s anti-racism team, which had formed in 2017, petitioned the lay leadership body to appoint a task force to officially study the windows.

Before the windows task force first convened, it became apparent that Highland’s work on the windows needed a broader scope. Around the country, unarmed Black people were being killed while jogging in a white neighborhood, sleeping in their own apartments or selling knockoff cigarettes.

Further, a national debate was stirring around the removal of Confederate monuments. Highland members wondered about their own windows and how the church benefited from white supremacy more generally. Thus, the ministry council created a reparations task force, in which the windows were one focus of four.

Starting in 2020, dedicated lay leaders, with support from me (Lauren) and my ministerial colleagues, considered alternatives for addressing the enslavers in the windows, the call to a congregational confession and repentance, the obligation to offer financial repair from the congregation’s budget, and strategies for ongoing advocacy at both a local and a national level for the study and gifting of reparations.

The task force wrestled together about the best path forward. Even as the COVID-19 pandemic continued, the group persisted on Zoom. First, we revisited our own history. In doing so, our objective was to consider how the church has benefited from racist systems, past and present, and to recommend a path of response.

Together, we produced a report, titled “Grant Us Wisdom, Grant Us Courage: A Historical Summary of Highland Baptist Church; Louisville, Kentucky; and Race, 1893-2021,” which tells Highland’s narrative through a lens focused on racial inequities.

Second, the task force wrote a report detailing all of the subjects depicted in the windows, especially noting the troubling figures involved in slavery. Considerations in addition to racism arose, and figures were examined in terms of antisemitism, homophobia and other forms of colonization.

We took care that our research was honest, without judgment. It was hard to acknowledge so much pain peppered throughout the windows’ design.

With new revelations over the months of research and writing, polarizing viewpoints were expressed privately among members of the church, and the murmuring complicated the work of the task force and concerned the ministers.

Anxiety threatened relationships in the congregation, raising the potential for real division. Some folks unknowingly sought to maintain the status quo. “Touching those windows would be an affront to the art and artist who created them,” they argued.

“They tell our story, even the parts of the story we do not like — do not mess with them,” others said.

Others focused on the money that would be spent if the windows were amended or contextualized. “Money spent on [changing] the windows would be better spent in the Black community,” some argued.

“Dismantle and destroy the enslavers immediately,” those distressed by the windows insisted.

Ultimately, the enslavers in the windows put our church at risk of losing members, as some indicated they would leave the church. “I cannot worship in a sanctuary that venerates people who owned other people,” they said.

Further, we hired consultants, leaders in Louisville’s Black community, for their feedback; naturally, their opinions differed as widely as those of the congregation. However, they unanimously agreed that the white Jesus figure in the revelation window needed to be darkened.

As the palpable discomfort among church members grew, our lead pastor, the Rev. Mary Alice Birdwhistell, and I (Lauren) preached on the controversy, but our messages did not readily alleviate tensions. For example, I preached two sermons in the summer of 2021 that spoke to the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and David McAtee.

In one sermon, I invited people to turn and look up at the figures who watched over the sanctuary. In so doing, I emphasized that the task force would and must continue discussing the windows, specifically the ones depicting Boyce, Furman and Mullins.

Though the sermon was an attempt to assure folks that the church would work together as a community to consider options, the effect was further division and angst. Contradictory pressures on the reparations task force emerged, with urging by different congregants to hurry up and to slow down, to stop and to keep moving. Even members of the task force were not in agreement. Zoom meetings were occasionally emotional and intense.

At this point, Mary Alice and I (Lauren) committed to communicating explicitly and frequently that the church would work through these issues together: by listening to one another, studying reparations in community and (in the words of the church hymn) being “brave of foot” in the race set before us.

In affirming the call to accomplish this work together, we began sharing with the church the benediction we co-wrote to conclude each task force meeting:

MAB: Friends, may God bless us with restless discomfort

in the work of reparations.LJM: May God bless us with holy anger at the injustices around us, and even within us.

MAB: And may God bless us with grief to honor all that has been lost along the way.

LJM: Until we meet again, may God continue guiding us toward liberation.

MAB: May Christ continue showing us the way of love.

LJM: And may the Spirit continue provoking us in this hard and holy work.

MAB: For even as this work challenges us, know that we are equipped and suited precisely for it.

LJM: Go in peace. Amen.

Highland’s leaders took collective responsibility for the church’s association with white supremacy, so we patiently urged a corporate response from the congregation.

In their book “Reparations: A Christian Call for Repentance and Repair,” Duke Kwon and Gregory Thompson write, “Some may insist that individuals and discrete institutions alone are responsible for the aforementioned failures, but this line of reasoning simply will not do. These sins are our sins.”

Calling out, initiating dialogue, responding to new knowledge — these are the practical steps we sought to enact ecclesially. As Kwon and Thompson state, “The church, after all, is one body, and its members are irrevocably bound to one another in Christ by covenant.”

Conversations continue with pastoral and lay leaders dedicated to accomplishing the work in community. The task force hosted three congregational listening and processing conversations. The first, in 2021 via Zoom, oriented around reading and discussing the history report. The second, in late 2021, also via Zoom, conveyed the four-prong approach adopted by the task force and solicited general thoughts on reparations. In 2022, a third conversation offered the opportunity to attend in person.

With repeated reassurances from many directions that the task force is not a decision-making body, members were able to participate in a hybrid meeting with earnestness, even amid uneasiness.

The task force presented its findings, and congregants asked meaningful and thoughtful questions. Members expressed their viewpoints with grace, and most importantly, all those present deeply listened to one another. The tenor of the meeting built up the confidence of the task force for its next steps.

Highland’s process to date reveals how the work of restorative justice is challenging for congregations dedicated to working in unison.

Our pastoral team and lay leaders are moving through the process of repair in a manner that includes all stakeholders without jeopardizing anti-racist values. At this point, the church has established a designated fund to receive donations specifically for reparations, and the church will commit 1% of its budget to the fund annually.

Further, the anti-racism team is researching the options of installing plaques that explain the church’s lament over the figures and why they are darkening the skin tones of the biblical figures, including the Christ figure.

Although no final decisions about the windows have been made, the reparations work continues taking shape on the racial justice journey. As a consequence, the leaders of Highland have achieved greater confidence in the capacity of our congregation to address controversy directly and to confront injustices in the world without compromise.

When my son was in first grade, he joined the chorus at his public magnet school for performing and visual arts. He was a reluctant singer, not a fan of being the center of attention, so I beamed and teared up when he and dozens of other children joyfully belted out “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” “(Something Inside) So Strong” and “It’s a New Day.”

I was proud of me, too.

Every day, I drove past the mostly white neighborhood elementary to drop off my white son at a school with as many Black and brown children as white children. I privately sneered at other white parents I knew who opted for much less diverse private or charter schools while my white son was singing songs, coached by three extraordinary Black female teachers, that demanded liberation, decried oppression and celebrated the election of President Barack Obama.

This scene could have been plucked from the New York Times podcast “Nice White Parents,” which traces the outsize influence of white parents on one school building in Brooklyn, I.S. 293.

Like some of the white parents featured in the podcast, I thought during my son’s early elementary years that mixing a diverse group of students in one school was the goal. If I could just be a nice white parent who said the right things and endeavored to raise a nice white son who valued all people, I was doing enough for diversity and equality. I clearly remember gazing at those beautiful children onstage and thinking, in a self-satisfied way, “This is what the kingdom of God looks like.”

But is it?

Does God prize a tidy vision of unity over justice? A pretty picture of reconciliation over liberation for all of God’s people from oppressive systems? A community whose primary demand on me is showing up to take pictures from the front row over one that asks me to acknowledge my privilege and use my power to love all those children as much as my own?

As “Nice White Parents” host Chana Joffe-Walt reports, Brooklyn school administrators are trying to help white parents see something I also needed to see those years ago: “Their mere presence in the school does not make it integrated. They have to work at making this place fair.”

Sociologist Margaret A. Hagerman, who studies how white children learn about race and racism, sounds the same message when she notes that many white parents focus on how to talk about race and manage individual children’s behaviors without questioning structures that benefit them.

Talking isn’t bad; it’s just wildly insufficient to address the socially constructed system of racialized oppression that privileges whiteness. Instead, she writes in San Antonio Review, white parents committed to anti-racism must focus on aligning their actions with their values and “make different decisions that prioritize the common good.” And doing that, becoming more than not racist, requires a regular, honest and humble reckoning with our identity, our history, our relationships and our world.

The church has a path for such reorientation, alignment and decision making. It begins with baptism.

In “Desiring the Kingdom,” James K.A. Smith writes that baptism creates a new “social and political reality,” a “baptismal city” where privilege of all kinds is erased, family is reconstituted to include all of God’s children, and all evil, injustice and oppression is actively resisted: “Our baptism signals that we are new creatures, with new desires, a new passion for a very different kingdom; thus we renounce (and keep renouncing) our former desires.”

Baptism is the beginning of a lifelong process, Smith writes, to learn to love what God loves and actively and intentionally join in the collaborative project to build a community animated by justice, peace and dignity for all.

But for many churches, our approach to baptism is insufficient to inaugurate such a radical reordering of our hearts, minds and lives. What would it take for white Christians to participate in founding a baptismal city?

We could start by “troubling the waters,” renewing the ancient ritual of baptism, the Rev. Dr. Brad R. Braxton writes in the “T&T Clark Handbook of African American Theology.” Baptism must engage our present reality, he says, acknowledging our culture’s violence and sickness and economic inequity and oppression of Black bodies.

How different would our practice of baptism be if, as Braxton suggests, it focused more on Jesus’ gruesome death that we join as we sink under the water? How different would our practice of baptism be if we focused less on the “cleansing of our souls from sin” and more on the “marking of our bodies for struggle”? How different would our practice of baptism be if the liturgy affirmed that Black lives matter by naming such martyrs as the Birmingham Four and the nine murdered at Mother Emanuel?

Matthew’s account of Jesus’ baptism, Braxton writes, has such a justice focus. In Matthew 3:13-17, Jesus agrees to be baptized by John “to fulfill all righteousness” (NRSV). That purpose is both personal and political, Braxton says, demonstrating Jesus’ participation in God’s mission to fight oppression.

Baptismal services that maintain a fidelity to Jesus’ baptism must, then, be much less polite and much more political, Braxton says: “Baptism is vacuous if it morphs into a genteel moment to acknowledge godparents, provide a gilt-edged baptism certificate with filigree font, and share an after-church baptism brunch for family and friends at an upscale restaurant.”

That sentence takes my breath away. As well it should.

In baptism, we die. In baptism, we are invited to renounce and resist the evils of the world, to love our neighbors as ourselves, to respect the dignity of every human being. In baptism, we give our bodies and all that we do to God’s struggle for justice and peace for all people.

Depending on our context, such action could look like reflection and education on racism, white supremacy, and implicit bias; donating money; marching; writing government officials; voting; challenging family and friends who make racist remarks; advocating for those whose voices are typically ignored; and constructing our daily lives to listen to and learn from people of color. Seeking and serving Christ in all people like this requires ongoing formation, repentance and returning to God.

That is what we promise we will do in our baptism. But is it what we practice? Or are we instead becoming and raising nice white Christians?