Luis Cortés: Esperanza builds an ‘opportunity community’ for Latinos in Philadelphia

Don’t tell the Rev. Luis Cortés that Esperanza is something special.

It is, of course. And he appreciates the compliment. But he doesn’t think that an institution like Esperanza, which serves the Latino community in North Philadelphia, should be special.

“A place like Esperanza should be normative. We have 30 neighborhoods in the city; there should be 30 Esperanzas,” he said. “There should be 30 places where you can participate in the arts, where you can learn about and play music, where you can experience different forms of dance, where you can learn photography, where you can learn how to add and subtract.”

Just because people are poor doesn’t mean they shouldn’t have the same things that everyone needs for a good life, he said.

Founded in 1987, Esperanza seeks to help the residents of Hunting Park, a majority-Latino neighborhood, have the same opportunities that other residents of the city enjoy. It focuses on education and economic development, including affordable housing, schools, housing counseling, immigration legal services, workforce development, youth leader training, and a fully accredited branch campus, Esperanza College of Eastern University.

The organization — its name means “hope” in Spanish — has more than 600 employees and a budget of more than $70 million and is a model for other institutions across the country.

Cortés, who is a Baptist pastor, worked with Hispanic Clergy of Philadelphia to found Esperanza. He earned an M.Div. at Union Theological Seminary and a master’s degree in economic development from Southern New Hampshire University.

In this interview, he talks to Faith & Leadership’s Sally Hicks about why he founded Esperanza and why he thinks institution building is key to social change. The following is an edited transcript.

Faith & Leadership: You have a goal of building an “opportunity community.” What do you mean by that?

Luis Cortés: Our ontology has a set of concepts and categories, and the relationships between these are fundamental. There is a Creator, and there are the created. Those are givens, as fact. So we start there. The other thing that’s given, as fact, is that all human beings are equal in God’s eyes.

If you believe that, then you must believe that we should try to provide a great opportunity for everyone to become that which God would have them become. To be in service to humanity is to assist everyone to develop to their highest potential. That’s our modus operandi.

This understanding then is followed by the question, what do you do with the poor? The mission work is to create a place where you provide all residents the opportunity to live a quality life. What must you provide for people to reach their ultimate goals, to be able to serve humanity better despite their economic situation and to have them feel they have a good quality of life?

This is what becomes an opportunity community, the development of all things needed for individuals to reach their potential. As an example, we built a theater and we have cultural pieces, like teaching dance, teaching music, all from a cultural perspective.

All people come from and have a culture. We have a language, we have music, and for Latines, we are in exile — we’re away from where our culture was based.

What do we do to create an opportunity community — a community that understands your class and your culture and helps you build so that you can have a great life staying here in this neighborhood or you can use what you learn here and have a great life elsewhere?

F&L: How did Esperanza begin?

LC: I was the founder of Hispanic Clergy of Philadelphia in 1981, an outgrowth of developing a field education system for Latine students at Eastern Baptist Theological Seminary. It was about 26 clergy from about 18 different denominational entities.

These clergy were all in the same Philadelphia neighborhood, and they had never really worked together until we organized as a field education consortium. As a group of clergy, when we would get together, like any group of highly motivated concerned citizens, we inevitably become active on challenging issues of the day.

We were getting together to discuss field education, quite mundane. And then all of a sudden, conversations shifted to, “They shot a guy here last week” or, “The police did or didn’t perform,” and we just moved in the direction of the conversations and became a civil rights organization.

During that time, Pew Charitable Trusts did a study on religious institutions, and as a result, we got funded for three years to start Esperanza and to work in clergy education. The clergy hired me to do it, with the mandate to do the clergy education and create a proactive organization, Esperanza.

In the beginning, the more we helped an individual family, the more it hurt the local church. As we helped individuals, the family moved farther away from their church, eventually joining a suburban congregation.

What we learned as a group was, it doesn’t matter if our people leave to improve their lot, as long as we create an institution that remains to assist those that stay or can’t get out.

Our philosophy became that we will work together to create Hispanic-owned-and-operated institutions. We began working on that theory of institution building where we could control the mission and agenda of our community, as opposed to the present-day external control.

We as Hispanic people in this nation have never focused on this on a large scale. We’ve never created our own institutions. What we do is we assume that we will inherit the institutions of America as we become a larger part of America. But that is not how it works. The institutions that provide for and control our neighborhoods are all managed externally: police, fire, schools, streets, most businesses.

So we decided we only wanted to create Hispanic-owned-and-operated institutions. We had enough Hispanic institutions that were doing social service, so we decided to not compete with our follow Latine agencies. We focused on education and economic development.

We wanted to do education because education is the first step and we understand institution-building as economic development.

When we first got started, it was like, “How do we help people?” Now it’s, “How do we help our institutions help people?”

F&L: How did you come to appreciate institutions in this time when there’s a lot of cynicism, a lot of distrust, a lot of anger around institutions?

LC: Since our nation’s beginning, Alexis de Tocqueville noted that it is associations and the institutions that they create that make Americas unique.

We’ve got to think positive. We serve our communities and our neighbors. So if everybody would do as well as they can at their community-serving job, whatever that is, we should be headed to a better place.

As the religious population lessens, there will have to be alternative institutions that defend the rights of the poor. Historically, the church has responded to the poor first through charity, then the development of institutions like hospitals or schools. Advocating to change unjust laws.

If that faith role dwindles, we have to figure out who or what replaces that. I see that as a major problem for the future.

F&L: In addition to the institutions, you are making change in individuals. The documentary “Esperanza: Hope for Our Cities,” for example, shows that commitment. Why do you stress self-belief, grit and confidence?

LC: I went to public school in Spanish Harlem. When I got to elementary school, they said to me, “You can be president of the United States.” And I looked around, and it’s old, it’s decrepit, it’s dirty, it’s outdated, and I’m like, “Nah, no way.”

For many people, it’s hard to self-motivate if you don’t see anyone else around you achieve success. We need our youth to “make it.” Last year, in our graduating high school class, we had MIT, two people at Carnegie Mellon, and one girl went to Wellesley, among a plethora of state colleges and universities. It is now normative.

Part of our model is we must have modern equipment. The space must be super clean. Visitors come to our place and they say, “Wow, this is so clean.” It’s a compliment. I understand. But it also says something about their expectation.

When I’m told, “Wow, this place is clean. This lab is so modern,” what are they saying? That in their preconception of economic poverty, they did not expect a first-class lab here. They did not expect, because of the economics, this place to be spotless. They do not expect your top five students to go to those schools, and you have one of the top college-graduating high schools for Hispanics. They do not expect that.

Whatever prejudice they brought in begins to be challenged, right? It’s like — look at this: MIT, Harvard, Penn. When they see that, they say, “Something special is happening.”

While there may be truth to that, it’s only special because other people won’t do it. Our team at Esperanza figured out how to do it, creating a culture of opportunity.

I believe there’s nothing that we can’t do. It’s just about how much time you have and what are your priorities. People ask me about this all the time — “How did you do it?”

Well, you find the need and fill it. And once you fill it, create an institution behind it, then find the next need and fill it. And once you fill it, create an institution that survives until it can thrive.

F&L: You mentioned the cleanliness, and you also insist on giving Esperanza’s students and other participants the best in other ways. Why is that important?

LC: We start with the concept that we should have what any community has. If you look at most communities and the arts, for example, they have access to experiences and ways to learn; they have ways to experience music, acting, dance and painting or visual. We have to create the avenues.

First we got the theater, and then through the theater, we do dance. But we also brought the best of the region. So the Philadelphia Orchestra plays at our theater; Opera Philadelphia sings in our theater; the Philadelphia Chamber Orchestra plays at our theater; Philadanco and the Philadelphia Ballet dance in our theater.

We communicated to these arts institutions, “When you come to our neighborhood, it has to be your A team.” Normally when they go to a community, they send the B and C team so they can work and practice as they serve a neighborhood project. At Esperanza, if the A team ain’t coming, you don’t come.

The artistic talent also has to give time during the week to work with students. Not just Esperanza schools, but there are about 10,000 public school children in our neighborhood. They do workshops and our community youth interact with them. After their theatrical performance, they sit and answer audience questions for 15 minutes. We have found the arts groups love these interactions as much as our residents do.

F&L: You also work on gentrification. How much of an issue is that for you?

LC: The bottom line is that urban communities near centers of our American cities where working-class Spanish-speaking people live are being dismantled by an upper middle class and above who wants their land and their housing so they can capitalize economically and culturally. It is happening everywhere.

Cities are happy with the gentrification or displacement of our neighborhoods, because it means a better tax base for the city. So when the city gains, the economically disadvantaged lose. That’s a constant struggle.

We need to build up equity in Black and brown communities. The No. 1 equity builder in Black and brown communities is not giant companies; it’s mom-and-pop commercial shops and home ownership. What we can show is, as we lose the housing, these mom-and-pop shops are destroyed.

So, the real question is, do we really want to help Black and brown people, or are we just saying we do while we actually cash in on their assets?

In America, they’re taking our neighborhoods under the guise of mixed income communities. In St. Louis, Black neighborhoods are being bought up by universities. West Philadelphia, it’s universities and science centers. North Philadelphia, it’s another university and the corporate needs. So they push people out of their long serving neighborhoods.

Today, young professionals don’t want to spend money on a car to live in the suburbs. They prefer to live in the city, not have a car. They’ll just Uber and use the money saved on transportation for restaurants and recreation, which is fine. But the economic burden falls on the economically disadvantaged, who need to move farther away to more expensive housing, losing the businesses that cater to their needs.

It’s interesting that progressive communities are the ones that gentrify Black and brown neighborhoods. It’s not the conservatives. Conservatives avoid minority communities, while progressives enjoy moving into a culturally mixed neighborhood until they extinct the original ethnic group that was there.

Progressives move in during their early professional career, purchase housing cheaply, live there for five years and make six figures on their “investment.”

It’s a real interesting dynamic where we fight the conservatives on one side and we have to fight the progressives on the other. They do have one thing in common: they’re white.

The role of the church should be different. How do we talk to progressives to say, “Listen, I know you can make money by moving into my neighborhood, but you’re hurting us. How do we really build a mixed income community?”

There’s a dynamic that’s happening in our country. San Bernardino, Phoenix, Calle Ocho in Miami, San Antonio, Philadelphia. Chicago, with three distinct Hispanic neighborhoods. They’re all under the same pressure.

F&L: How do you keep from being overwhelmed when everything you describe is extremely complex? It’s difficult. Yet almost 40 years later, you’re still hopeful.

LC: I am a minister. I believe in God. And in the end, we are all called to serve others. Despite all the problems, our job is to persevere and pursue. And persistence is the name of the game.

When we first got started, it was like, “How do we help people?” Now it’s, “How do we help our institutions help people?”

Brian Ide is on the road. He’s somewhere between Flagstaff and Albuquerque, headed to Amarillo and points beyond, traveling cross-country to talk about a topic that, in this moment, feels both vitally important and virtually impossible to achieve.

In his new documentary, “A Case for Love,” Ide raises the possibility that unselfish love could be a bridge across the nation’s significant social and political divides.

The topic plays out through conversations — some with people the film’s crew literally walked up to on streets across America, others with individuals and families deeply engaged in living out love through challenging situations. And there are interviews with recognizable figures such as Al Roker, the Rev. Becca Stevens and Presiding Bishop Michael Curry.

The son of a Lutheran pastor father and Catholic mother, Ide has worked in the entertainment industry for more than two decades, founding Grace-Based Films in order to start telling faith-centric stories that weren’t being told in Hollywood. He had joined the vestry as a parishioner at All Saints’ Episcopal Church in Beverly Hills and quickly recognized that conversations about stewardship and pledging shortfalls did not play to his strengths.

“It could be a long [vestry term] — or maybe we could start telling stories and utilizing other gifts in our parish because of where we were,” Ide said he thought. “Especially back then, [what] was coming through Hollywood was centered around, if your faith was strong enough, then your football team won and your marriage was reconciled.

“We thought, ‘Who’s telling the stories about the messier, more complicated conversations, where you don’t get the big football win?’ It was born out of there.”

“A Case for Love” is Ide’s fifth film and first full-length documentary and will be showing in wide theatrical release for one day, Jan. 23. Ide spoke with Faith & Leadership’s Aleta Payne during a promotional tour. The following is an edited transcript.

Faith & Leadership: There are a lot of entry points into the conversations featured in the movie, including for people who are not from a faith background. Was that intentional?

Brian Ide: That was really important to us. Through the course of the filming, we had one story that was inside a church, because the story itself was about somebody’s faith journey. Then Al Roker, when he agreed to do a cameo for it, wanted it to be at St. James’ [Episcopal Church], but other than that, it is a story about ordinary people.

It is not a propaganda machine for the Episcopal Church or for the Christian church. It’s not a story about telling you what to believe on any of these entry points that you’re talking about; we are not experts on anything. It is truly a journey story about bringing human beings back together again in a time when it feels like we’re all being pulled apart. What can we take from being exposed to people’s intimate, vulnerable stories? We were really intentional about not hiding from it but also trying to do something that had a broad reach.

F&L: You feature such a breadth of people. How did you find and choose them?

BI: The film itself is broken into four groups of people, and the bulk of it, probably 95% of the whole film, are these deep-dive stories of ordinary people that cover a range of topics that are woven together into seven chapters. It’s usually two, maybe three of these stories woven into a single chapter, and the chapter itself has a universal theme — so a chapter on love and loss or a chapter on being dealt a difficult hand or a chapter on answering the call.

We knew early on it was really important that the bulk of the film be about ordinary people, because we wanted it to be for ordinary people so that, hopefully, they’d be inspired or moved or motivated to do something in their own life. If they see it’s Bob and Susan doing this, then they’re like, “OK, well then I think I can do that.”

Whereas if all we had was a bunch of CEOs and Mother Teresas, it would be, “Great for them, but I’ll never do that.” So that was really intentional; that’s really the heart of the film.

There were a handful of those that we had lined up before we started the filming tour, and two of them were military. We knew that it was important for us to explore the military space and that intersection of what we assume is this community that has to face conflict and war and death sometimes, and how does that intersect with love. We were just fascinated by the power of that.

Beyond the four or five we originally had lined up, it was trusting in the Holy Spirit to start in Minneapolis and be with people. And they’re like, “You’re going to Indianapolis? Listen, you really need to meet with Tim Shaw. Let me see if I can make that happen.” And the rest of the stories ended up coming from the journey itself revealing [them].

It was this mix of being intentional and planning about having diversity in the stories but then letting the Spirit guide. I love that, because we ended up being with the people that we were supposed to be with, and they weren’t people that were chosen because they’re experts on any of these topics; they’re just people. We’re in their homes, and we’re creating a space that’s vulnerable enough and safe enough for them to open up about their particular journey.

That’s the deep-dive portion of it. Then we were fortunate enough to have access to these notable figures, and those were politicians and actors and rabbis and Muslim leaders and NGO leaders. That helps Hollywood see that they can have something to sell a ticket on, when you have these notable faces and names in there.

The third group are people on the streets. We had probably 200, 250 of those, where we just pulled over [and approached them] everywhere, from downtown Indianapolis to the Brooklyn Bridge to just a small row of farms in Pennsylvania. We would just pull over and then walk up to people and ask them about what comes to mind when they hear the words “unselfish love,” and where have they seen it in the world and where have they seen the absence. Those were probably the interviews I enjoyed the most, because of how eclectic they were, how surprising they were.

After all of that, we sat down with Bishop Curry and said, “OK, you’re the teacher. Here’s what we saw. What does this mean?” He’s just beautiful about speaking to the human condition.

F&L: What a faithful way to have set out to do this, to discover the voices you needed along the way.

BI: I would say that. Or terrifying. One of those two. I think it’s a little bit of both. But it was a trust, which I loved.

F&L: What surprised you or resonated with you from these conversations?

BI: A couple of things. This first one wouldn’t be a surprise but would be a reinforcement for me that we are way more connected than the headlines of the world want us to believe.

Most of us are trying to figure out how to take care of our families and loved ones; most of us are trying to figure out what our purpose is on this planet; most of us are trying to figure out how to be kind. And most of us find that pretty tough at times. In being with people and talking about those things, where we were on some political issue or social issue never came up. Just the human part of the dialogue came up. It reminded me and reinforced for me — and that gave me hope — that we are very much connected.

The surprise part of the journey was probably the people-on-the-street times, because we’re a crew of eight. It’s a big camera package. We have big sound equipment and all of this. When you walk up to somebody and they’re walking to the grocery store to get their lunch and you pull them aside, I think everybody’s first sense was skepticism.

The surprise of it was that as soon as they believed what we were about, then there was this lifting of spirit across the board and there was a sense of, “You want to know what I think? Nobody ever asked me what I think about that and holds that in value.”

I saw that time and time again. When that happened, they shared incredibly beautiful, vulnerable, intimate things that they probably never in a million years imagined they would tell a group of strangers on camera on their way to work.

That surprised me, not knowing what that part of the process would be like, and I think that’s probably why I enjoyed them so much.

F&L: You talked to children and to young people and gave value to their stories as well.

BI: What I loved about the young people is they don’t tell you as quickly what they think you want to hear — they tell you what they think. That gives me hope too, because we’re all born with a pretty good soul and a pretty good view of what love is and instincts of what love is. To sit with them reinforced that.

I think the next project is going to be centered around young people in some way. I think, this last handful of years, that they’re absorbing toxicity at a rate that we’re not fully aware of, and I think that they’re struggling in a variety of ways. So I want to do something to serve them.

We had a national educator see one of the screenings of the film. He was like, “Can I create a discussion guide that uses our language in schools for young people?” He created a free one for seventh through 12th graders (it’s on the website and free to download) that uses the language of young people and educators. That was a beautiful thing.

F&L: Where do you hope to go with this particular project, and what’s next for Grace-Based Films?

BI: For this one, Hollywood is in an enormous period of transition right now, and I think they’re trying to figure out what models are working and not working. Is it streaming? Is it not streaming? What kinds of movies do they greenlight?

For films like these, they don’t usually get significant platforms. And when they do get platforms for faith-centric movies, historically, a lot of them have been catered to big evangelical megachurch worlds.

It’s much harder in the Episcopal, Presbyterian, Lutheran worlds to do that, so they just haven’t been given the megaphone in that way. It is really important to me to do everything we can to show the business analytics side of this, that there is an audience for these stories.

We were offered this theatrical release, which is in almost 1,000 theaters nationwide, provided by Fathom Events. (Fathom is owned by AMC, Regal and Cinemark.)

They created this company to create opportunities to add new content to midweek auditoriums and theaters, because most of their box office happens on weekends. They can now offer it to films that aren’t “The Avengers” and “Avatar” and give them opportunities like this.

The way it’ll work for us is that we’re in theaters on Jan. 23 for one day only, as most of their films are. We push all the attention toward that, and the success of the attendance and engagement with that will then dictate, “OK, does that mean that Netflix is next or Amazon is next or Peacock? What streaming opportunities? What opportunities are there for military bases?”

All of those have this tiered downstream process dictated by Hollywood. Much of that will be on the success of Jan. 23.

I try to plan for the next one, and I realize, every time I do, that I’m wrong. But I really do feel this pulling toward something that is youthful. I want to travel again and spend time with [young people] and listen for, like, “OK, what are the things that you all are talking about, and what are you not hearing, and what are you not saying?” and then mirror that with the power of storytelling, probably in a scripted movie, not in a documentary. To find something in that space is where my heart is right now.

F&L: You address head-on that some people might view this movie cynically. Bishop Curry says in the film, “Someone could say that’s naive, but sometimes what we call naivete actually are ideals we don’t want to deal with.” Could you speak to that as a filmmaker?

BI: As we were in the earliest processes of dreaming this up, I was sitting with a writer-producer friend of mine who’s done this for a long time in Hollywood, and he said, “OK, here’s the deal. You have a documentary about love. You have an older, ordained minister as the inspiration for it. The vast majority of people are going to look at that and be like, ‘I already know what that is. I don’t need to watch it.’ Or some people will be like, ‘I want that,’ but they’re going to assume that they already know what it is.

“Your job as a filmmaker is to say, ‘You thought it was this? It’s actually this.’” That drove so much of the way I went about this process, and Bishop Curry was really focused on that as well.

He says it over and over again when I’m with him, and I’ve heard him say it to many other people too, that this is not a sentimental love. He said, “What I’m talking about is not sentimentality. Unselfish love is a very different thing.”

When you hear “unselfish love,” it forces you to take a beat, because you don’t usually hear those two words together.

Sometimes jarring people can be good. There are going to be some stories that are jarring. We have some really beautiful, simple, heartwarming stories in there, and then we also have a story of a woman who was sexually trafficked from the time she was 5. We have the whole gamut in there, because different people need to hear different things, and also to remind us that these are complicated things.

All of those things drove how we go about this, so it doesn’t get written off as a churchy thing or a Valentine’s Day thing but instead is like, “No, we really need to have these conversations as a human being thing.”

We’re seeing the effect of not having these conversations, and it’s not great. Those were driving forces for us.

F&L: What haven’t I asked?

BI: I’m a hopeful person. This film is funded entirely by donors across the United States, from individuals to foundations to parishes to all kinds of people. I don’t own any of the profits from it. Bishop Curry doesn’t own any of the profits from it. The people that funded it don’t own any of the profits. They all go toward telling stories that serve people. I’d love for that to come across. Because sometimes, I think, in the cynical world that we’re living in, it’s like, “OK, is this guy hopping around all over the place trying to get people to buy his product so his product is successful and he becomes successful?”

It is important to me that people know that that’s not the driving force of why we or the people that funded this made it happen. I do like sharing that, and I think people will be surprised — I think they’ll be moved by this.

We didn’t want people to go to a theater or watch it at home for two hours, be entertained or be moved, and then go back to their life. We wanted this to instigate something; it’s part of the launch of 30 days of unselfish love. So the call people will hear in movie theaters on the 23rd, the call is, when you go home, for the next 30 days, be intentional about seeking out — every day — some act that works in your world of unselfish love and journal about that. What is the impact on you, and what did that mean to you?

There are journals on the website too. They’re beautifully designed, and they’re free; they’re downloadable. Our CFO was the one who came up with this, and he’s a very Type A, analytical, list-driven person. He started this, and he put it on his whiteboard each morning.

What he found was that by the sixth day, it became a habit. Our belief is that acts turn into habits and habits create change. We invite people to use this and then find out whatever [is next]. A lot of the NGO partners — folks that are doing really great work that have come on board, like kindness.org, dosomething.org, racial justice programs and neighborhood collaboration programs — if somebody’s moved by the faith element of this, if they’re moved by the volunteerism element of this, here are groups that do that really well.

Take this as an instigator toward action. We hope that people see that too — that this is more than just a moment in time.

Shouldn’t we get it by now?

From the inside looking out, we’re aware of the dimming daylight even as we’re typing away, chasing children, on another Zoom. And then we check the time: only 5:15. Whoa.

We’ve observed “spring forward, fall back” our whole lives. We’ve made it through our share of winters. We understand the shortening of days and lengthening of nights. We know how this works. Don’t we?

And yet here we are, year after year, still surprised, still looking outside and saying, “Can you believe how dark it is already?!” (Or, in the words of a TikTok I still think about, “Bro, it’s 5:15! What?”)

When we think of Advent, the themes of darkness, expectation and (im)patient anticipation often come to mind. ’Tis the season to watch and wait. But there’s another element of this time of year that I want to dwell in: the element of surprise.

When we’ve grown up in the church, or even when we’ve simply attended for long enough to know the lyrics and liturgies, the story of Christianity can become a little too familiar. For us and for our salvation he came down from heaven, we may find ourselves droning along each Sunday, focused more on our lunch plans or what remains to be accomplished before Monday’s return. We may grow so accustomed to the mysteries of our faith that we throw around terms like “incarnation” and “ascension” in a way that strips them of any mystical meaning.

But can we back up just a few steps?

[He] was incarnate from the Holy Spirit and the Virgin Mary

and was made truly human.

Think about how you’d “translate” this into normal, everyday language. God chose to be like us, putting on our flesh forever. That’s a crazy, crazy story.

For our sake he was crucified under Pontius Pilate;

he suffered death and was buried.

On the third day he rose again.

No wonder the early Christians got some weird looks (and, well, worse).

“Historically, [Christianity] was a surprise because Christianity was born and emerged and grew in a Roman world that had no expectations for it, didn’t know what it was, and couldn’t have anticipated it,” says C. Kavin Rowe, a New Testament scholar. “Christianity was something that the Roman world had never seen and didn’t even have categories for.

“Christianity was surprising also in its particulars,” he adds. “It introduced patterns of life into the world that caught people by surprise in a good way.”

It’s safe to say that at this point in history, Christianity — at least in the way most people conceive of it — is not much of a surprise. It’s pretty mainstream: no longer a fringe movement. But just dream with me for a second. What if the good news — in all of its particulars — became surprising once more? What if we were as astonished by it as by evening’s early arrival?

Yes, there can be plenty of comfort in familiar rhythms and words, but what might it look like to reclaim some of that wonder — not just for shock value, not just because we’re bored or distracted, but in a way that honors the story we have received?

Maybe it’s as small as reading the passages we know by heart in a new translation for a few days. Maybe it’s looking them up in the Art Search from the Calvin Institute of Christian Worship and seeing some of the creativity those passages inspire. Or maybe it’s simply changing the posture we take when we approach the old, old stories.

How might we be caught off guard?

We joke about the changing seasons surprising us, but the brief days and long nights still startle us each year — “How is it dark already?!” “The sun is already up!”

I hope the jarring reset of our clocks and microwaves and (non-smart) watches might nudge us to do a bit of an internal reset too. I hope the changing church seasons might surprise us as well— that, in some weird and wonderful ways, we might be amazed this Advent by the bizarre, glorious truth of the baby who was God-with-us, the God-man who sits at the right hand of the Father, still wearing his human skin and bearing marks of Roman nails.

I hope we never get used to it.

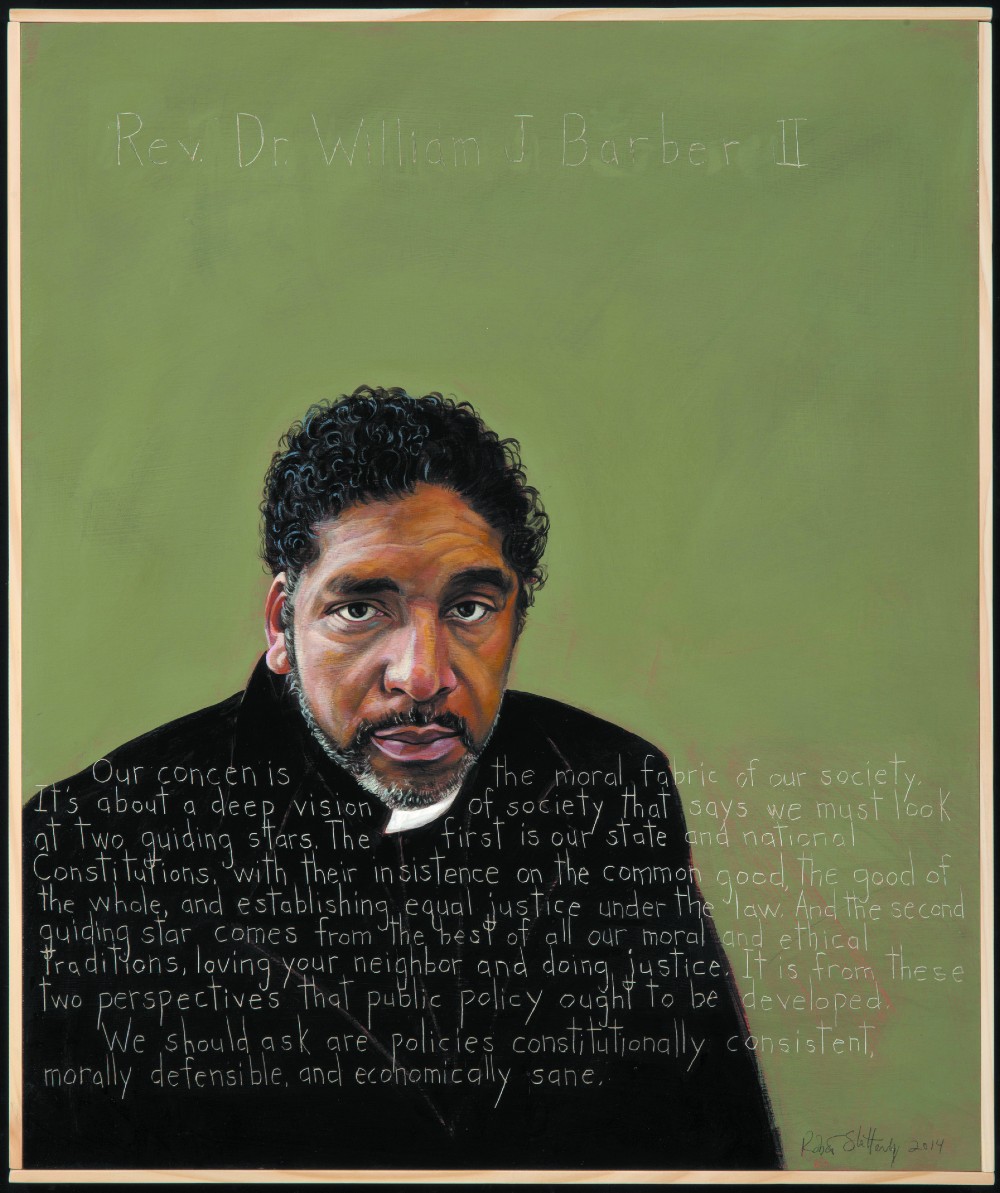

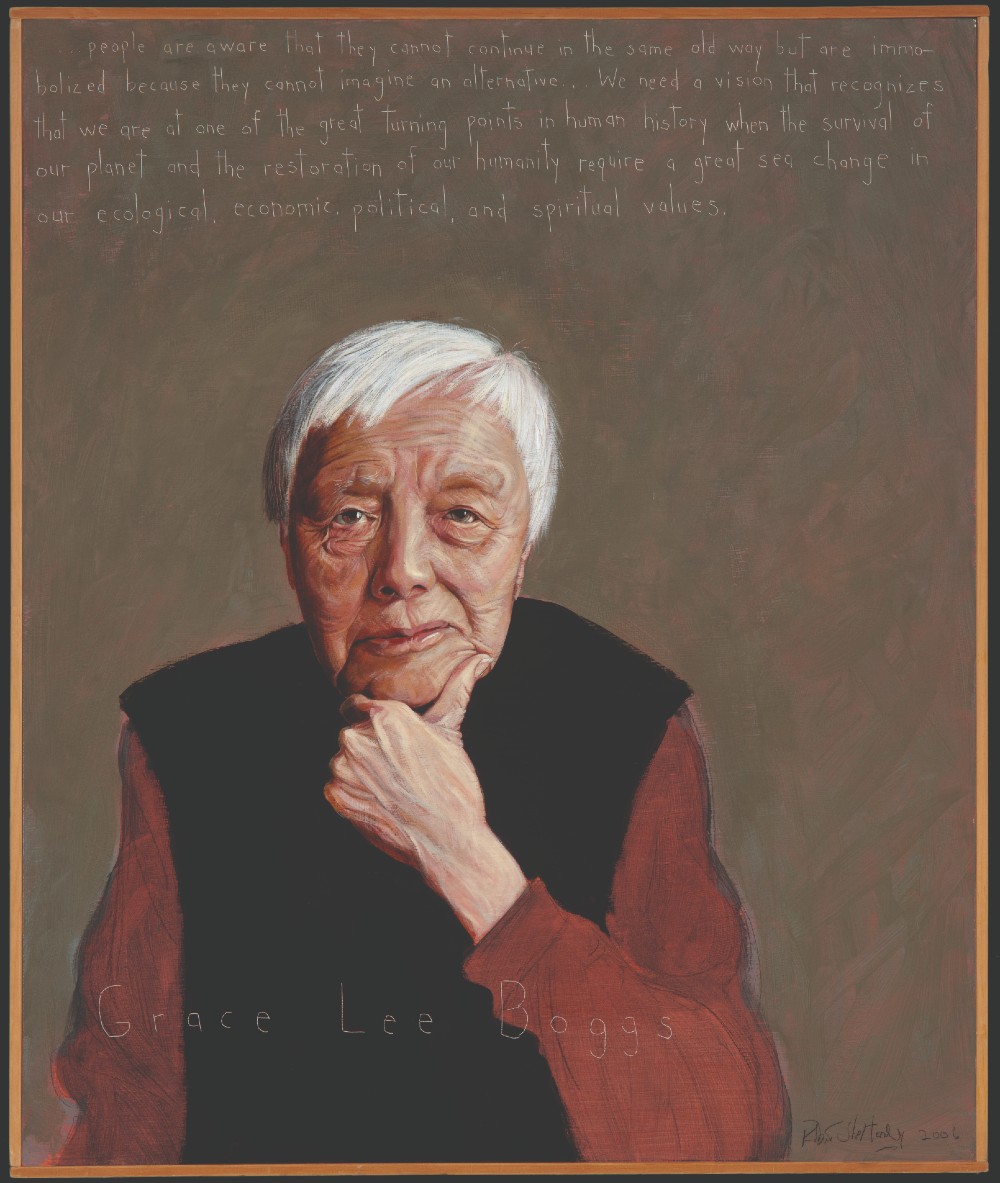

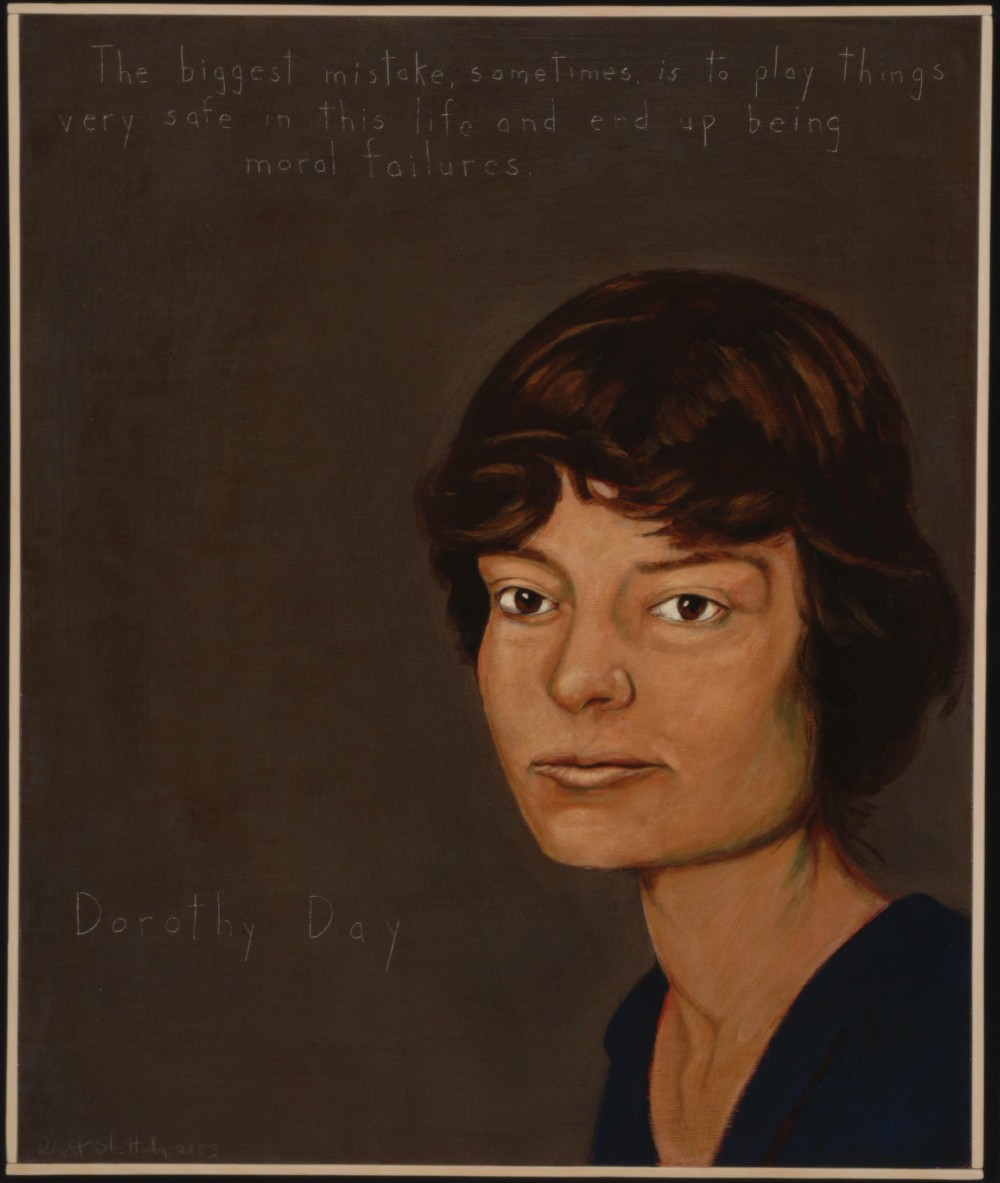

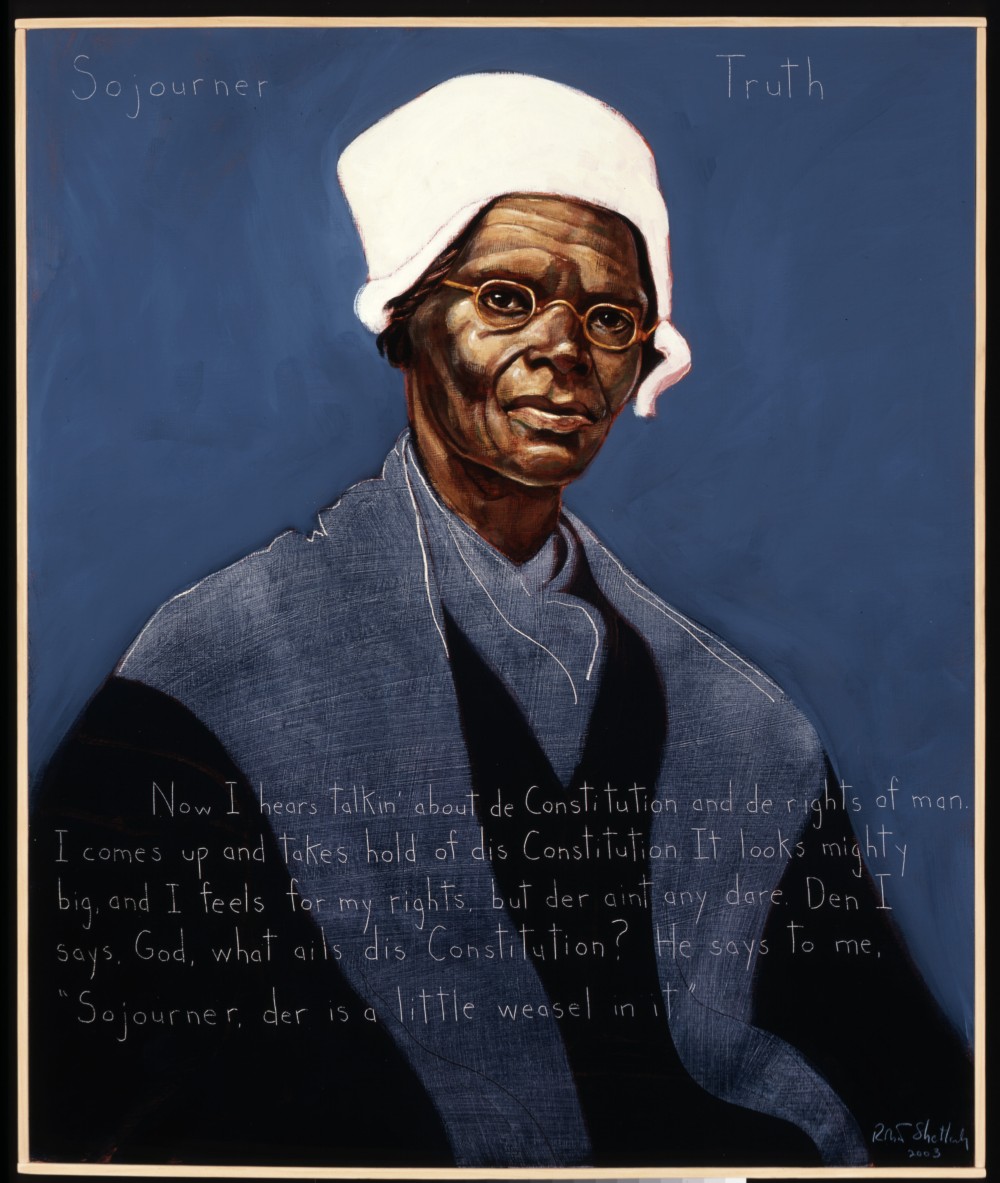

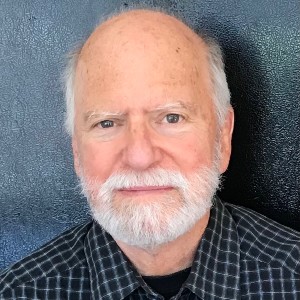

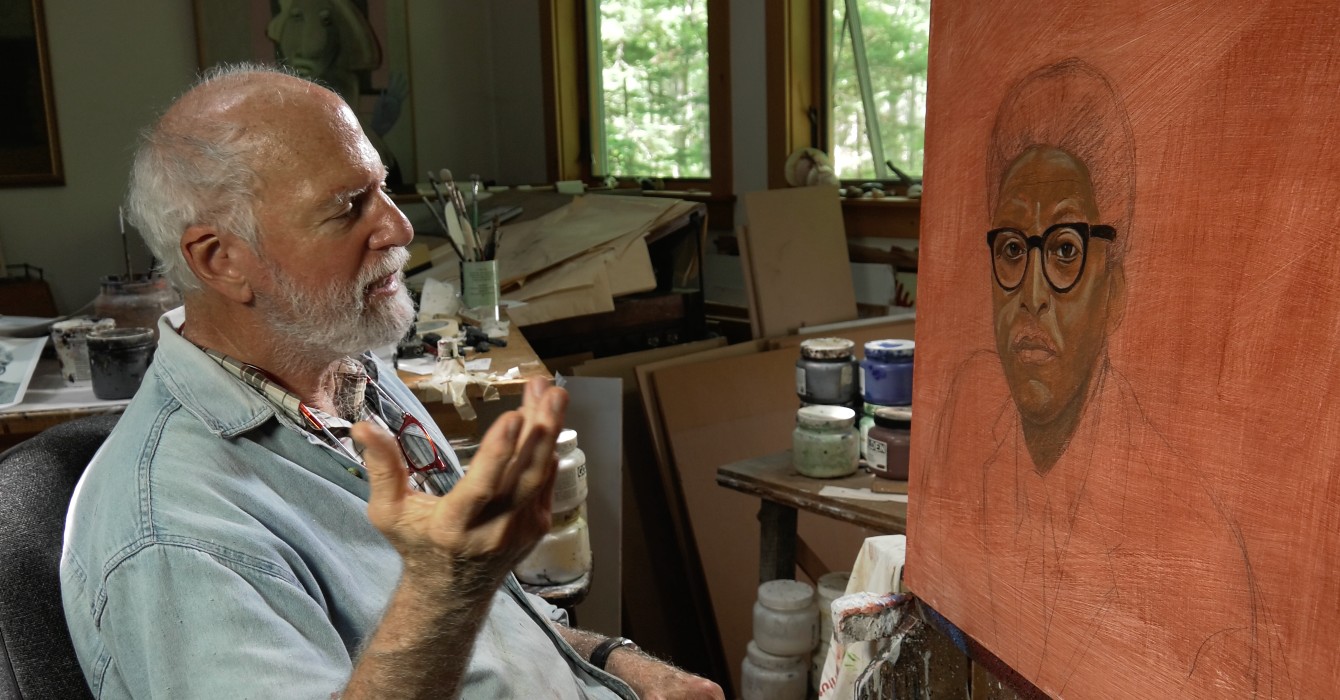

When Robert Shetterly taught himself to draw and paint, he became fascinated by the themes of nature, animals and religious forces. He began making a living by creating art from his home in Maine. But eventually, that wasn’t enough for Shetterly, who’d been an activist for civil rights and against the Vietnam War during his high school and college years.

After the events of Sept. 11, 2001, and the United States’ subsequent invasion of Iraq to destroy “weapons of mass destruction,” Shetterly found himself in a rage over what some have since called flawed intelligence and others have called lies.

“All I could do was rant. And I was really making myself sick,” Shetterly said. He wondered whether he should leave the country or stay and use his talents to have a voice.

The desire to speak out won, and Shetterly started painting portraits of people from the 19th century who were courageous in standing up for what they believed in, such as Harriet Tubman, who had helped lead hundreds of enslaved people to freedom via the Underground Railroad.

“I thought, OK well, ‘How can I use this enormous energy that I’ve got right now, because of how I feel, and do something positive? Something that’s about love rather than hate?’”

Since then, Shetterly’s “Americans Who Tell the Truth” project has grown to more than 260 portraits of those living and dead.

“[T]he more I did it, I realized this was not just about my own personal relationship with the country or my own therapy. It was really about education,” Shetterly said.

Today, he continues to connect to communities through painting and through exhibitions and other events. His work travels to settings like museums, schools and faith communities. The documentary “Truth Tellers,” directed by Richard Kane, shares the story of the artist’s work and journey, and encourages people to connect and discuss themes of truth, justice and equality.

Values of faith and honesty

It’s no coincidence that many of Shetterly’s subjects are people of faith and that faith communities have exhibited his work.

“We are encouraged often to think about finding our ethics in our economy, in how many jobs have we got, are people being paid a fair wage, what kind of innovation can we do,” Shetterly said.

But in faith communities, he said, fundamental values like compassion, dignity, truth telling and courage are the ones that must first align.

Shetterly said his faith-focused subjects are people who believe in these values and understand that they can’t live with themselves if they don’t act on those values. When his work is exhibited in faith communities, it can spark conversation and introspection.

What are your faith community’s stated values, and how do they align with your action?

In 2022, Shetterly was a guest speaker for chapel at St. Paul’s School in Concord, New Hampshire, focusing on themes of truth and justice. Speaking to an audience of 650, including 500 students at the residential school, Shetterly shared the story of one of his portrait subjects, Claudette Colvin, who as a Black teenager in 1955 Montgomery, Alabama, refused to cede her seat to white passengers months before Rosa Parks would famously do the same.

St. Paul’s students attend chapel four days per week. There, they grapple with big spiritual questions like, “Who am I?” “Who are we?” “What does it mean to be a good and ethical person?” said the Rev. Charles Wynder Jr., the school’s dean of chapel and spiritual life.

Shetterly’s visit, including his discussion with art students later in the day, brought to life the work, sacrifice, vision and life’s journey of people who have sacrificed for the common good, Wynder said.

For Bethany Dickerson Wynder, the school’s director of diversity, equity, inclusion and justice initiatives, Shetterly’s artwork complemented the school’s efforts to lift up “unsung heroes” in the Black community and supported the school’s focus on education in the arts.

Prophetic voices

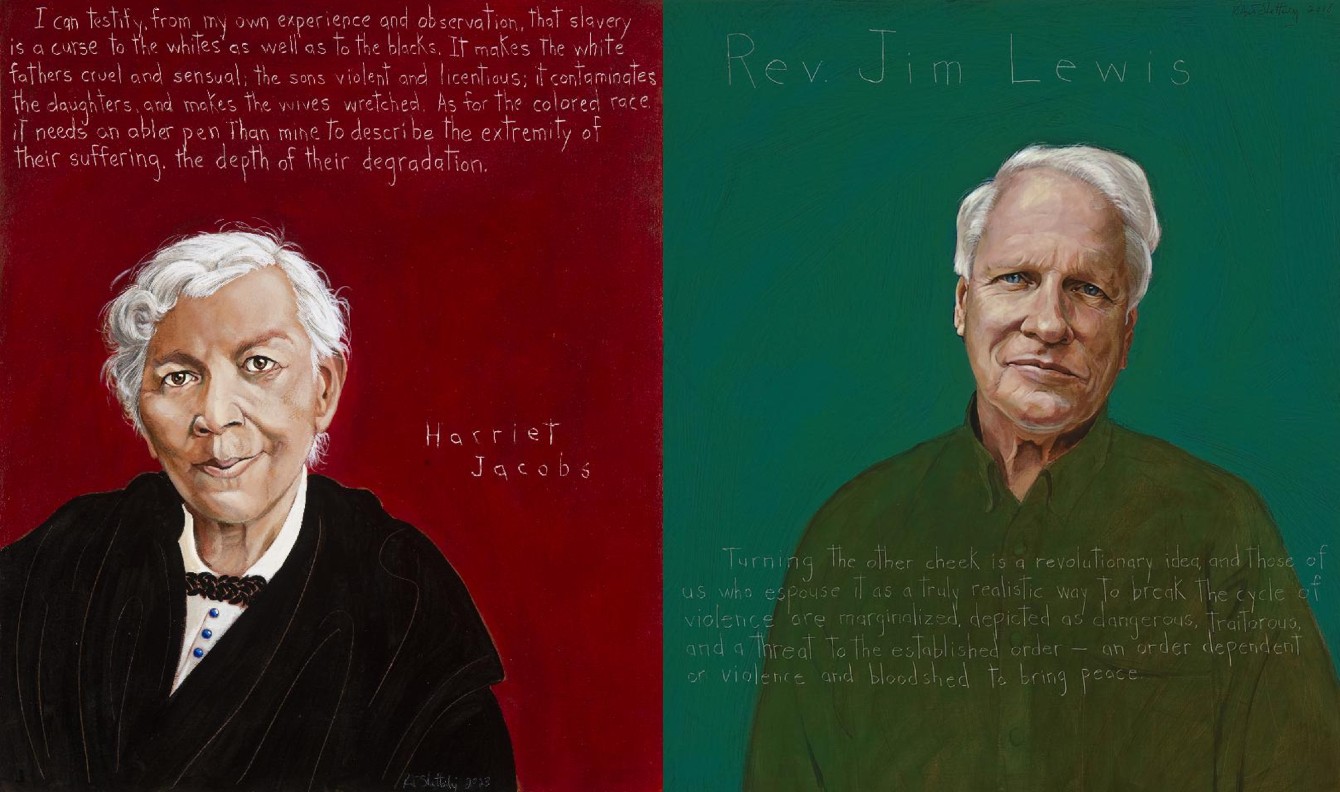

Shetterly’s portrait of the Rev. Lennox Yearwood, the president and CEO of the Hip Hop Caucus and an elder in the Church of God in Christ, features the subject wearing a dark-colored blazer and a matching hat that reads “Resist.”

“Often, the greatest leaders come out of that tradition — that prophetic tradition in the churches,” said Shetterly, who explained that he didn’t want to paint his subjects as icons or people on pedestals.

“This isn’t the work of a few heroes and giants — this is the work of people,” he said.

The Rev. Dan Smith, the senior minister of First Church in Cambridge (Massachusetts), Congregational, United Church of Christ, has helped share Shetterly’s art in a faith-based setting. Smith engages with the church’s collaborative staff on social justice tasks as well as deep spiritual formation work.

Before the pandemic began, Smith’s church had reached out to Shetterly’s team after seeing the artist’s work in Maine. The church had been doing a deep dive into its own legacy of slavery — finding that there had been more than 30 enslaved people in its historic membership and doing the spiritual work of repair by visiting sites like Selma, Alabama. But the timing wasn’t yet right to connect with Shetterly.

Who are the prophets without pedestals in your faith community making change right now? How can you learn from them?

In 2022, the church reached out again, looking ahead to the theme of “Truth that sets us free” for the season of Lent. First Church went on to offer an exhibit that ran from February to June 2023.

The staff chose portraits that connected with the church’s story, whether by geographic proximity or because their words inspired the community. For example, there was a special local connection with the unveiling of Shetterly’s portrait of Harriet Jacobs, an abolitionist and author who had freed herself from slavery and run a boarding house near the church grounds after her escape, Smith said.

“The congregation loved having the portraits. They were immediately inspired when they walked into the building,” he said, noting that staff had scattered the art inside and created a ritual of standing before two images at a time and having a short prayer along with time to hear the subjects’ biographies.

He said the hope is that the exhibit will return, noting that there is a connection between the branches of social justice and the spiritual roots of worship.

How can your faith community use art to more fully and accurately represent itself? To challenge itself?

“When a congregation gets too focused on prayer life without looking out beyond itself to what’s going on with its neighbors, that’s problematic. I think when a congregation is all about social justice and doesn’t tend to its prayer or worship life, that’s also a problem,” Smith said. “I think the sweet spot is when there’s a real sense of balance and integration and alignment.”

One example from Shetterly’s work would be the portrait of the Rev. Jim Lewis, who has focused on issues like health care and criminal justice as an Episcopal clergyperson and author. It depicts Lewis looking out stoically from a blue-green background, with his quote reading, in part, “Turning the other cheek is a revolutionary idea.”

A documented legacy

If the unveiling and display of Shetterly’s portraits is an experience, so too is the act of painting them. The process is so inspiring, in fact, that it spurred director Richard Kane to document it.

“‘Truth Tellers’ is the most important and most difficult film I have made in my long journey of producing almost 100 films,” Kane wrote via email.

“I began following Rob around 2003 in his process of selecting his subjects, interviewing them about their beliefs in the ‘American experiment,’ selecting a quote from their writings, and painting their portraits,” Kane wrote.

“It soon became a series about his belief in returning to the founding ideals of our country — liberty, equality and justice for all. It became a series of discovering one’s moral courage. And it was courageous of Rob to select many lesser known but significant Americans who symbolized our fight for justice — racial, indigenous and moral justice.”

Kane noted Shetterly’s deep belief in democracy is what drove the desire to create the film.

“At a time when there is a pattern of states denying the right of students to study slavery, inequality, diversity, critical race theory, preventing students from learning about our true history, ‘Truth Tellers’ is here to tell the truth and give teachers a tool to have students understand our real history,” Kane wrote.

For his part, Shetterly remains committed to sharing his message and his craft.

“The first thing I do with each painting is I paint the eyes,” he said. “As soon as you paint the eyes on a wooden panel, [it] actually seems like there’s a life there.”

Instead of relying on brushes, Shetterly said, he paints a lot with his fingers, building up thin layers of paint using a technique called glazing. Eventually, the light comes through the paint, and the emotions of his subjects begin to surface, allowing Shetterly to then scratch their words onto each wooden panel, using a dental tool, to bring the elements together.

Early on, for historic subjects, Shetterly painted from existing images. But for subjects still living, he has also traveled to those who are willing to meet in order to understand their stories and capture their images in real time. Today, he has a list of hundreds of people he can paint, including names suggested by others.

Does your faith community ever engage explicitly in the discussion of values like truth, honesty and integrity?

Capturing emotions

Shetterly’s meetings with the subjects might require less than an hour of guided conversation that he hopes will shape their facial expressions, and he then may take just 20 to 30 photographs that capture their emotions in the moment. These days, he can even carry out the initial meeting via FaceTime instead of an in-person visit.

When it comes to the actual painting, Shetterly can finish in about a week to 10 days, but he often spends more time traveling and researching each portrait.

Some of those he approached were wary to participate at first, he said. But after the publication of his first book and the launch of his website, subjects could see the company they were going to be in, he said, and would rarely refuse to sit.

And even though many of the people he’s painted were first unknown to him, many — like Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha, the pediatrician and public health advocate who revealed the truth of the inhumane conditions in Flint, Michigan — have become friends and even guests for related events. Regardless of whether subjects follow up with program events, the experience can be meaningful.

Kathy Kelly, who was co-founder of the grassroots campaign Voices in the Wilderness and now is president of the board of World BEYOND War, remembers sitting for Shetterly in the early 2000s. At the time, she’d returned from overseas travels where she’d seen children, who couldn’t get pain medication or antibiotics due to economic sanctions, withering away in hospitals.

“It was at a point in time where I felt a little fragile. I think in the painting maybe I look a little fragile,” she said, recalling that it seemed clear that the economic war would become a bombing war.

“Our group really wanted to raise the voices for people who had no voice in the United States,” Kelly said.

In contrast to the difficult scenes she’d witnessed overseas, Kelly’s portrait session was set in a welcoming space by the water, she said.

“Rob Shetterly exposed many, many truths through his amazing portrait artistry that would never have seen the light of day,” she said of his body of work. “And I love it that he does it with [paint] and a few words.”

Portrait subject Louis Clark had a similar positive experience, coming from his work representing and protecting government and corporate whistleblowers via the Government Accountability Project (GAP).

After helping Black voters register and get to the polls in 1960s Mississippi, he had earned his master of divinity degree from Pacific School of Religion before obtaining his law degree from American University in 1977 and becoming director of GAP in 1978, just after its launch. With Clark at the helm, the organization assisted whistleblowers.

Today, Clark calls out the role of faith in the work his portrait highlights.

“A pretty significant percent of the people that come forward are coming forward because they have ethical concerns and convictions, very often religiously based, about what’s right and what’s wrong,” he said. “Because, essentially, what we’re doing is helping people in the workplace to realize their ethics and their morality. And to me, that’s exactly what it’s all about in terms of religion. That is the narrow path — the narrow path of righteousness is truth itself.”

This kind of work — and the willingness to go beyond accepted norms — has historical significance in the church.

“What we know about the history of Jesus is that he was a radical,” added Clark, who is ordained in the United Methodist Church.

“For example, he ate with unclean people. His ministry included — in leadership roles — women, which was pretty unheard-of in the day,” Clark said. “[Jesus] recognized the humanity of all people.”

It’s this kind of action that Shetterly’s project continues to recognize and share for discussion and contemplation. The portraits, and the related documentary, can help inspire and encourage others to tell their own truths, explore their own stories and look out into their own communities.

“What Robert Shetterly does is he tells narratives of truth so that those who look at his images, his paintings, and hear his story … will live into a truth that is loving, life-giving and liberating,” said Charles Wynder, of St. Paul’s School, noting that the essence of truth allows us to liberate ourselves.

“Developing global leaders who pursue truth — seek to live it, strive to tell it, work to protect it — is foundational to not only our faith journey but the aims of religion and faith: to see the divine in others, to find ourselves together [in a way that] recognizes our connectivity and our particularity,” Wynder said.

What radical parts of Jesus’ ministry does your faith community embrace, and what parts does it ignore? Why?

Questions to consider

- What are your faith community’s stated values, and how do they align with your action?

- Who are the prophets without pedestals in your faith community making change right now? How can you learn from them?

- How can your faith community use art to more fully and accurately represent itself? To challenge itself?

- Does your faith community ever engage explicitly in the discussion of values like truth, honesty and integrity?

- What radical parts of Jesus’ ministry does your faith community embrace, and what parts does it ignore? Why?