‘When God’s Call Is Bigger Than a Building’

Invitation to a Changed Life

As the visioning of the congregation continued, [Arlington Presbyterian Church] members connected the crisis of their own congregational life to the life of the surrounding community. In 2012, APC realized they needed to set their priorities within their call from God to the neighborhood.

We really needed to stop asking ourselves questions and start knocking on our neighbors’ doors in a sincere, committed, and organized effort.

It wasn’t enough to do the intellectual discernment processes or for the congregation to assume they knew the needs of the neighborhood.

We were challenged to pay attention not to what we thought needed to happen, what we imagined the community needed, but to listen to what our neighbors had to say — to get to know and be in relationship with our neighbors and hear them.

Congregants rode buses up and down Columbia Pike [in Arlington, Virginia]. They talked with local business owners, teachers, domestic workers, any and all who make up the infrastructure of Arlington County. On Saturday mornings, church members set up tables in the church’s parking lot, located right next to a bus stop. They used the community-organizing strategies of listening sessions and one-on-one meetings to listen to the deep wisdom of the neighborhood.

One day in one of the villages there was a man covered with leprosy. When he saw Jesus, he fell down before him in prayer and said, “If you want to, you can cleanse me.” Jesus put out his hand, touched him, and said, “I want to. Be clean.” Then and there his skin was smooth, the leprosy gone. (Luke 5:12-13)

APC listened. They heard of people covered in debt and exorbitant rent. They heard of people longing to be healed from weary commutes, financial uncertainty, and living away from family and kinship. They listened as neighbors shared hopes, dreams, and ideas for their future, a future they wanted to be in Arlington County.

This relational work allowed a guiding question to emerge for APC: What is breaking our hearts in our neighborhood?

The stories of the neighbors broke the heart of APC, binding the well-being of APC up in the well-being of the neighborhood. Jesus pulled the congregation into the neighborhood streets, and they practically tripped over the need for affordable housing as they listened to story after story.

The stories signified the emerging incompatibility with the old and the new: as we began to think about jettisoning our 1950s building, we also started to rid ourselves of the 1950s version of Christianity that had captured our thinking. Our ministry shifted from “if we build it, they will come” to “we will go to the neighbors and build.”

It wasn’t about what we could do for our neighbors; it became about how we heard God’s invitation in their stories. How their stories became our stories together. …

For More of the Story, Go Around the Corner

There is a plaque on the outside of Gilliam Place [apartment building], created by an unknown entity, that says “Here stood the Arlington Presbyterian Church.” The plaque names how APC played a significant role in the life of the South Arlington community. The end of the plaque reads, “The Church property was sold in 2016, and the buildings were demolished in 2017.”

The end. It reads like a church obituary.

Not to be outdone by a building plaque, several APC folks want to put up a sign at the bottom of the plaque that reads, “for more of the story, go around the corner …”

Creating new wine for a new wineskin hasn’t been easy, and God isn’t finished with us. Right now, APC stands in the tension between our previous stories and the ones we hope will guide us forward. As we claim these new stories, we see ourselves sharing life and evolving with those in Gilliam Place.

I now realize how our new space has allowed us to begin living a new future together with our neighbors that would have been inconceivable in the old building.

We are still dynamically breaking open those old models of church. We stand in the community, asking questions about new ways and new directions.

We commissioned a new hymn to honor this new era of APC at Gilliam Place. We sing these words often in worship:

We have been called to listen and called to act, we have been called to tear down and called to build, and we’re still people on a journey, our work isn’t done. Keep us faithful in the way of love.

This hymn is a reminder that God is not done with APC even after this miraculous story. We’re still people on a journey, drinking new wine in a new wineskin. For all of this — for the old wine and old wineskin, for the new wine and new wineskin — we give God never-ending thanks.

Excerpted from “Gone for Good? Negotiating the Coming Wave of Church Property Transition,” edited by Mark Elsdon © 2024 (Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.). Reprinted by permission of the publisher.

The formerly enslaved artisans who constructed First African Baptist Church in Beaufort, South Carolina, sometime after the Civil War didn’t use nails. Metal was expensive and often hard to come by for Black builders less than a generation from bondage.

The Rev. Alexander McBride, First African’s senior pastor, explained how the laborers built the church in Gothic Revival style, noted for its signature pointed arches and windows. The current building replaced an antebellum praise house, an open one-room clapboard space with little furniture so the enslaved could engage in a more mobile, joyful service removed from white surveillance and sit-quiet worship styles.

“They used the mortise-and-tenon method, where they interlock the wood. And this church has withstood every hurricane” that has rolled through the coastal city, said McBride, the 16th pastor at First African in its more than 150 years of existence.

And there have been many storms. An 1893 hurricane drowned many of the town’s Black residents, stranded in low-lying areas or swept to their deaths. But even that massive storm didn’t cause significant damage to the church, thanks to the unnamed craftsmen who may have lacked nails but had possessed the skill and wisdom to use the strongest joint known to woodworkers.

The church’s biggest current enemies are time, termites (which have eaten their way through some of the structure’s undercarriage) and moisture — largely unavoidable menaces for a century-old building in a humid seaside town.

Earlier this year, First African was among dozens of historically Black churches to win grants from the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund. Those monies, through the Preserving Black Churches initiative — $4 million in this funding cycle — will support projects that recast their sites’ history through new interpretation or exhibits, grow capacity through staff hires and community outreach, and repair aging or damaged buildings.

Diversity of spaces

The grantees highlight the diversity of Black worship spaces and the history of how Black Americans have fought for religious freedom and built their own institutions amid racism and violence. They include institutions such as 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, which just marked 60 years since the Ku Klux Klan bombing that killed four girls and damaged the church; the elegant Black-majority Basilica of St. Mary of the Immaculate Conception in Norfolk, Virginia; one-room churches built by hand and heart; and churches in places with historically small Black populations, such as Alaska and West Virginia.

“Black churches are living testaments to the achievements and resiliency of generations in the face of a racialized, inequitable society,” said Tiffany Tolbert, the Action Fund’s senior director for preservation. “They’re foundational to our Black religious, political, economic and social life.”

In some places, a church is the only building that remains as an artifact of a Black community that no longer exists. Scotland AME Zion Church in Potomac, Maryland, not far from the nation’s capital, is one such example from a community swallowed by encroaching development and urban sprawl.

Religion scholar C. Eric Lincoln once described the Black church as the unchallenged “cultural womb of the Black community.” Fellowship halls and sanctuaries in Black churches have long functioned as multipurpose rooms, where worship and politics meet. Churches like Beaufort’s First African have been incubators for Black social enterprise; during Reconstruction, First African was the site of a school for freed people, hungry for the literacy denied them during slavery.

Numerous historically Black colleges, civil rights protests and social movements trace their origins to Black pulpits and pews. Preserving church spaces can thus have a multiplying effect, documenting as well the stories of Black communities at large and the work of Black architects, artisans and mutual aid.

Worthy of preservation

It’s commonly said that the church is “more than the building,” yet buildings are material remnants of history and culture. What kinds of meaning do church buildings have for you?

That’s the case with the Halltown Memorial Chapel, built in 1901 not far from Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, where abolitionist John Brown and his band of brigands in 1859 had raided an arsenal in hopes of ending slavery. The one-room chapel is small, only about 40 feet by 50 feet, with room for 13 pews. It was built of rubble stone by church members, stone masons and laborers who also constructed a nearby turnpike or worked at the local paper mill, which has since closed. Services continued there for decades, only ceasing after World War II because of a dwindling congregation. After that, it hosted the occasional gathering until its last event — a wedding of one of the founders’ descendants — in 1988.

Kim Lowry, the treasurer of the Halltown Chapel Memorial Association, cataloged the many repairs needed via email. “Water damage from a hole in the roof and from water seeping in under the foundation was the culprit. And without regular events or services, the chapel suffered from neglect. The plaster walls needed to be rehabilitated, the flooring had rotted and deteriorated and required replacement, and exterior work was required on the wood window sills and frames and the Chapel entrance area.”

Powderpost beetles had chomped on the pews, spreading ruin with every bite. One of the church’s three stained-glass windows was missing altogether, and the others needed restoration. One is a poignant tribute to Edna, a church member’s child who had died in infancy. Such design features — with references to congregation members who fundraised for such elements — are tangible history, traces of people long gone and their efforts to build beloved community.

“It’s impossible to talk about American craftsmanship without talking about the Black and Indigenous hands that constructed it even before 1776,” said Brandon Bibby, a senior preservation architect with the Action Fund. “It’s important to preserve that aspect so that we as a society don’t forget. By preserving, we are saying, ‘This place matters in the whole context of the American landscape.’”

“What I want most is that through this project, Black congregations and communities will see the value and beauty in their places and see they are worthy of preservation,” he said.

Does your church have a historic role in your community? How has its role changed over the years?

Recognizable elements of church design can be particularly vulnerable to deterioration. Steeples are both symbolic and pragmatic communicators; their towering presence in a landscape announces where people can worship or seek shelter. Yet sitting aloft, largely inaccessible, placing strain on dramatic, heaven-pointed roofs and often channeling rainwater to places it shouldn’t go, steeples can be a source of problems that go unnoticed until a leak sprouts or cracks appear.

Many of the Preserving Black Churches grant recipients need steeple repair. When congregations are forced to choose among costly repairs, a steeple can sometimes take a back seat to high-traffic areas with more visible problems, such as the sanctuary itself.

Funding a range of needs

What traditional elements of your church are difficult to maintain? Would your congregation be OK without them?

Declining church attendance has meant less coin in the collection plate and, in turn, fewer resources for maintenance and repairs. Black American church membership has dropped in recent years, from 78% in 1998-2000 to 59% in 2018-2020, though Black Americans remain one of the top populations most likely to be church members (along with conservatives and Republicans), according to a multiyear Gallup poll released in 2021.

A 2012 Kellogg Foundation report also found that Black people give more of their income to community-based causes than whites, in part because of a culture of mutual aid, lack of access to white-dominated institutional funding and traditions such as tithing. Even so, when an evangelical research firm surveyed church financial well-being, more Black pastors said their congregations had less than seven weeks of cash reserves — perhaps because they are dependent on a community with lower wealth in the first place. Getting money to repair churches can be particularly difficult.

Following the first grants that went to 35 churches across the country, recipients of another $4 million will be announced in January, Tolbert said, as part of a plan to distribute between $8 and $10 million, with support from Lilly Endowment Inc. In total, $20 million will be invested through Preserving Black Churches across all of its program goals.

If you were asked what in your church is worth preserving, what would you say? What would your congregation say?

That funding will go not only toward capital needs, Tolbert said, but also toward planning, to help churches understand how to undertake preservation. Matching grants will help churches create new preservation endowments so that invested income can be used to support maintenance and preservation of existing buildings. Emergency grants are also available to address immediate issues such as damage caused by floods, fires and even acts of vandalism.

And the Action Fund is working with six churches — four in Alabama and one each in California and Chicago — to help develop comprehensive stewardship plans that will address restoration and rehabilitation of the buildings along with programming and interpretation, activating space for community, and bringing in arts and social justice programs. They will benefit from a consulting team of architects, engineers, business planners and capital campaign fundraisers.

“It is essential that these places are activated,” Tolbert said. “They are centers of worship, but also, they continue to serve the community.”

Action Fund executive director Brent Leggs told The Washington Post in an interview that Black churches are exceptional lenses through which to view Black and American history. “It’s amazing to see centuries of Black history told at historic Black churches. Some of the stories include formerly enslaved Africans moving through emancipation, beginning to form communities, … and some of the earliest buildings founded by African Americans in the United States [include] a Black church. These places are of exceptional significance. Their stories matter, and they are worthy of being preserved.”

Would members of your community benefit from learning more about your congregation’s past and its role in local history?

Questions to consider

- It’s commonly said that the church is “more than the building,” yet buildings are material remnants of history and culture. What kinds of meaning do church buildings have for you?

- Does your church have a historic role in your community? How has its role changed over the years?

- Steeples are a traditional element of many churches, yet they can be difficult to maintain. What traditional elements of your church are difficult to maintain? Would your congregation be OK without them?

- If you were asked what in your church is worth preserving, what would you say? What would your congregation say?

- How is your space “activated” for your community? Would members of your community benefit from learning more about your congregation’s past and its role in local history?

In his 1954 poem “Church Going,” English poet Philip Larkin stops by a church and finds himself wondering:

When churches fall completely out of use

What shall we turn them into, if we shall keep

A few cathedrals chronically on show,

Their parchment, plate, and pyx in locked cases,

And let the rest rent-free to rain and sheep.

Larkin died in 1985, but his poem lives on. And the question it poses is ever more urgent for congregations across America.

Each year, thousands of churches in the United States close their doors and others begin to move toward that decision. While post-pandemic statistics on church closings are not yet available, 2019 estimates placed church closings between 1% and 2% annually, or between 75 and 150 congregations every week.

Even thriving congregations may struggle to maintain buildings that no longer align well with mission and ministry. Often silently, sometimes aloud, pastors and lay leaders and religious support organizations are asking Larkin’s question: What should become of these buildings — what shall we turn them into?

Yet congregations need not feel alone in this struggle, as hard as the struggle may sometimes be. In fact, the problem of church buildings is generating significant conversation and creativity across the American landscape.

The question of what happens to church buildings means different things, of course, depending on context:

A 700-member church in the heart of a depressed Midwestern city faces the triple challenge of declining membership, a campus reflecting decades of deferred maintenance, and spaces that, while plentiful, do not match the congregation’s needs.

A church in a growing Southern city faces a different dilemma. Its longtime neighborhood has become the “it” spot and is now thriving with restaurants, shops and new residents. But the church building is falling apart to the point of being unsafe. Most members no longer live in the neighborhood and have no resources to bring the building back to a useable condition. A quick sale to eager developers would bring in millions for the denomination but give up a key strategic location where ministry is needed.

A congregation out West with a big campus has a thriving ministry and a constant need for more space. At the same time, members are fervently focused on and engaged in mission and outreach in the surrounding city. This has led to dynamic discussions about how to balance “infrastructure needs” with a strong desire to serve the city and deploy as many resources as possible toward that vision.

A small church in rural Maine watches its congregation shrink each year. There is no booming real estate market out its front door. But several community groups use the fellowship hall for meetings, and most members have someone buried in the churchyard.

A 200-member congregation in a Northern city is challenged by a building that, as one member describes, “works for us if you squint really hard.” The building has more space — and maintenance demands — than the congregation needs. And while financially stable now, the church is faced with a giving base that is aging.

A large church moved farther out into the suburbs from its large city several years ago and built a large, cheaply constructed building. Over the next decade, it will cost at least $5 million just to maintain the parking lot, replace the windows and deal with a leaky roof.

For this multitude of challenging contexts, a multitude of groups and organizations stand ready with suggestions and support.

Who can help?

A growing number of independent organizations offer tailored resources and consulting.

For more than 30 years, Partners for Sacred Places, the longest-standing national nonsectarian organization working in this arena, has been helping congregations better understand the architectural, historic and community value of their buildings in order to preserve and use the property for good.

Newer organizations like RootedGood are crafting cohort experiences and human-centered design tools to guide congregations toward new plans for their properties.

Oikos Institute for Social Impact is helping faith communities of color harness the power of their assets and especially their real estate, often their most valuable tangible asset, for community benefit and economic growth.

The Proximity Project is encouraging congregations to understand the built environment of their properties and neighborhoods as essential to mission, drawing on the insights of urban design, development and placemaking.

Some organizations are geographically focused. Bricks and Mortals (which wins the award for best name in a highly competitive field!) focuses on New York City congregations, connecting faith communities with development experts to find sustainable solutions to property woes.

Good Acres builds collaboration among real estate professionals, investors, community organizers, and church and denominational leaders in San Antonio to help churches realize the full potential of their underutilized property for community good.

Wesley Community Development partners with faith-based organizations and churches in North Carolina.

And north of the U.S. border, Trinity Centres Foundation works with congregations in Canada.

Other organizations approach congregations through a specific social concern that repurposed church assets might help address: affordable housing, food security in Black communities, co-working spaces for change makers, ecological land stewardship or venues for artists, to name just a few.

Meanwhile, denominations continue to provide programs like Project Regeneration (Presbyterian Church [U.S.A.]), the Episcopal Parish Network (formerly CEEP) and the UCC Church Building & Loan Fund. They also share resources with one another cross-denominationally, and increasingly engage the growing landscape of independent consultants.

Where can you start?

Larkin’s question, once prescient, now presses. What shall we turn them into? And yet, as all these organizations and consultants will tell you, the first step is not to rush toward a solution — even a solution they might advocate and ultimately help support.

The first step is a set of actions that every church can and should take right now:

- Start a conversation in your congregation about how your building is a tool for ministry and mission.

- Build a wider web of relationships in your community, as those will be essential to any future action.

- Expand your ecclesial imagination about possibilities for the future use of your building.

One of the easiest ways to expand ecclesial imagination is to reflect on what other congregations are doing.

Faith & Leadership offers many articles about church buildings that can start the reflection. Drawing together these and other stories, Lake Institute on Faith & Giving has created the Faithful Generosity Story Shelf, stocked with short vignettes of congregations and other religious organizations who have repurposed their buildings, lands and funds in creative ways. A brief discussion guide offers ways to start the conversation.

You’re not alone in your concern about the future of church buildings, whatever your context. There is a shared sense of the challenge and a growing network of groups with poetic names, ready to respond. Together they offer resources that can lead to a much greater good than Larkin’s worried vision of churches “let … rent-free to rain and sheep.”

On a bright Sunday morning in September, the congregation of Turner Memorial AME Church gathers at its Hyattsville, Maryland, building. A pastor is delivering an impassioned message. Applause crackles through the space as worshippers lift their hands under the sanctuary’s vaulted ceiling.

But the person speaking from the pulpit is not the Rev. Dr. D.K. Kearney, Turner Memorial’s pastor since 2015. The preacher is the Rev. Cesar Moreno, a minister originally from Guatemala, who is sharing the day’s word — in Spanish.

For nearly two years, the pastors’ churches — one an African Methodist Episcopal (AME) congregation more than a century old, one a largely Latino nondenominational congregation established in 2010 — have been sharing the Turner Memorial building.

It’s more than just a transactional arrangement. Church members have worked carefully and intentionally to build the relationship between the two congregations, which includes regular shared services and, this fall, the “Soul Saving September Revival,” a four-week joint endeavor.

It involves the close friendship of the two pastors, as well as the efforts of 16-year-old interpreter Josary Moreno Mejia (a preacher in her own right and the granddaughter of Cesar Moreno).

“In Christ, there is no Jew or Gentile. There is no race or color,” Kearney says later that Sunday from the pulpit, after Moreno’s message concludes.

The Turner Memorial pastor looks out on the congregation, which includes members of Iglesia Evangelica Horeb Asamblea de Dios (Mt. Horeb for short) — the church pastored by Moreno and his wife, first lady Loly Moreno.

“We cannot allow the world’s culture of division to separate us. We cannot allow the enemy who comes to steal, kill and destroy to separate us,” Kearney continues, getting louder. “We are one in Christ Jesus.”

It is this focus on unity that exemplifies Turner Memorial’s activities, efforts deeply rooted in the church’s traditions — including, for example, its long-standing relationship with a local synagogue. Kearney is now working to unify the Turner Memorial and Mt. Horeb congregations under one roof, as together they reach out to the surrounding community.

This work is important to both pastors.

“As followers of Christ, we are to follow Christ’s example. And the example which he laid out during his ministry here on earth centered, in my opinion, around community, and building community, and living in community,” Kearney said. “As a church, that which represents Christ, we are to serve our community with the hope [that] by serving the community we win persons over to the family of God.”

Moreno agreed. “Speaking spiritually, people need salvation. People need to be on a better path. This is the objective, to teach people the path of God, … so that new generations can have hope and live better,” he said.

A ‘God-ordained’ relationship

When Kearney became pastor of Turner Memorial in 2015, he was working on his doctorate of ministry with a focus on liberation theology at Payne Theological Seminary. He found, through his research, that the church’s surrounding community was in large part Latino.

He wanted to reach those community members and began considering different ways the church might connect beyond its walls. He also began leading the church in a series of workshops focused on deploying spiritual gifts to make an impact.

Time passed — Kearney calls it a period of “preparation” — and in 2017, Moreno and his granddaughter began attending Turner Memorial services while seeking a space for Mt. Horeb.

When the two pastors met, they realized they could create opportunities for their congregations — one English-speaking, one generally Spanish-speaking — to worship together. They began partnering in December 2017.

Are you open to opportunities that might come your way?

The two developed a friendship that Moreno’s granddaughter Mejia describes as “a brotherhood.”

“They both have said and shared that when one comes to preach to the other’s church, they speak and help lift the other’s spirit,” she said.

Kearney elaborated: “It never fails that every time when we are together, even when we are meeting, I cannot help but to feel the presence of God. … It gives me the confirmation that what is happening is God-ordained.”

Today, Mt. Horeb holds its own services in the Turner Memorial building. But on the second Sunday morning of each month, its members join Turner Memorial’s. There, Moreno preaches in Spanish while his granddaughter interprets.

And on the fourth Sunday evening of each month, Turner Memorial members go to Mt. Horeb’s service, where Kearney delivers a message that Mejia translates into Spanish.

For Kearney, the combined worship reflects a core value of intentionally building relationships. Turner Memorial also has a partnership with the historic Washington, D.C., synagogue Sixth & I — located in the building that housed Turner Memorial for 50 years before the congregation moved to Hyattsville.

Kearney and Senior Rabbi Shira Stutman speak at each other’s place of worship each year during the weekend of the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday.

“[Kearney] is amazingly generous with the pulpit God has assigned him to,” said the Rev. Dr. Natasha Jamison Gadson, Turner Memorial’s minister of leadership growth and development.

As long as Kearney senses that speakers have the Holy Spirit and that they are focused on the same goal of serving God, she said, “he is open with the pulpit for other pastors to come and share.”

Being open to others — interacting with diverse communities — provides an opportunity “to learn something we don’t know about God, our neighbors and the Christian life at large,” said Ismael Ruiz-Millán, the director of the Hispanic House of Studies, Global Education & Intercultural Formation at Duke Divinity School. He also directs programs within the divinity school for non-Hispanic clergy and laity who want to serve the U.S. Latino population.

In what ways could your congregation expand its notion of Christian life, and act upon it?

“If we really believe that all human beings are made after God’s image but we insist in keeping ourselves in circles with people who are just like us, then we really have an incomplete notion of who God is and what the Christian life is about,” Ruiz-Millán said.

The community commitment

In general, both community and church members have responded to this outreach. For instance, on the Sunday before the first Friday revival in September, representatives from the two churches handed out more than 7,500 flyers to share information about the coming events.

“I think it is such a great experience,” said Joan Goodluck, a Turner Memorial member originally from Guyana who identifies as black. “I am seeing God’s work being revealed, because he wants the nations of the world to come together.”

Now 78, Goodluck grew up in a Christian home and attended church with majority-black congregations for much of her life. She said that hearing the word in both Spanish and English has been a learning experience for some worshippers, adding that the preaching of the word “helps me to grow more.”

Mejia, who devotes her time to ministry while taking high school and college classes as part of her high school’s dual enrollment program, is a big part of this growth.

She regularly interprets for services at both churches — including translating from Spanish to English at Mt. Horeb for young people who don’t speak Spanish.

In this way, she provides clear messages to congregants and community members even as the pastors speed their cadences and raise their voices.

Are there ways in which you serve others that you could reframe as ministry?

“I thank God overall, because it’s a blessing,” Mejia said after one Sunday morning service at Turner Memorial.

She asks God to speak through her lips when she preaches as an individual and when she interprets for the pastors, she said.

During the service, Kearney noted that Mejia does a “wonderful job” (a message she humbly interpreted).

And as Mejia stood outside the sanctuary afterward, people hugged her, with one woman telling her, “You are such a blessing.”

Others too have positive thoughts about the churches’ union.

“I think it’s something really good — good because God calls us to be one body in Christ,” said Evelyn Chávez, a Mt. Horeb member.

“We share the gospel, first. But we are not only sharing the gospel. … There are people with needs. They need clothes; they need many things,” Chávez said.

A new kind of innovation

A pillar of the young partnership between these churches is the September revival series. In past years, Turner Memorial has held revivals featuring pastors from outside the community. But when planning this year’s activities, Kearney said he felt he needed to go out to the people instead of waiting for them to come into the church.

He committed to having the two churches gather outdoors along with neighbors from the community. Members of both churches worked together to plan events.

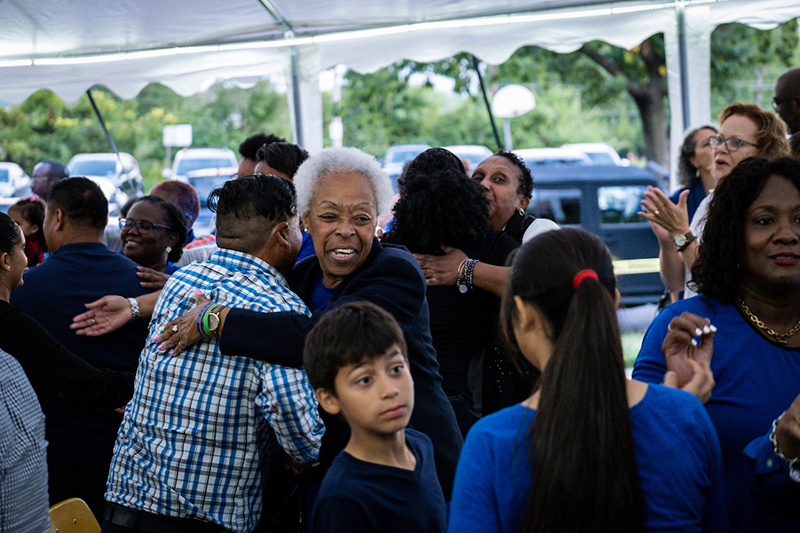

On the first Friday in September, rows of colorful chairs were lined up outside the building, under a large white tent.

A band that included a singer, a keyboardist and a drummer played lively Christian music with Spanish lyrics as children toddled around in the grass and older attendees wearing everything from T-shirts and jeans to dress shirts and pants wandered among various outdoor booths.

At one booth, stacks of clothing ready to be given away were so plentiful that the church halted donations for the revival’s second week. One booth offered voter registration; another, immigration information.

Reaching out together with Mt. Horeb, and having activities in both English and Spanish, including those offering community aid, may be an innovation on the traditional revival.

“When I look at tradition and the church, what we are doing is traditional,” he said. “Because on the day of Pentecost, when the Holy Spirit fell, Scripture says that everyone heard the gospel being preached in their native language. And that day 3,000 souls were saved.”

In what ways could you innovate on tradition in your context?

But people can allow personal preferences about language, race and social class to separate them from others, Kearney said.

“And I would dare to say, don’t confuse one’s preference with tradition. Because traditional church teaches us that all of God’s children — regardless of language, race, class — gather together. And that when the Holy Spirit falls, everybody hears the good news,” he said. “If this is innovative, it is traditionally innovative.”

Light in the darkness

On the first night of the revival, attendees gathered under the tent as the service began, reading song lyrics from copied pages so they could worship together.

“Promise keeper, light in the darkness. My God, that is who you are,” they sang before switching to Spanish. “Cumples promesas, luz en tinieblas. Mi Dios, así eres tú.”

Have you worshipped or sung in other languages? If not, what might you learn from that experience?

“We have come to let the enemy know that no race, no language barriers will stop us. We are not trying to build walls, but we are building bridges,” said Kearney, standing at the front of the tent, as Mejia interpreted.

Moreno then delivered a message in Spanish, telling those gathered that Jesus is the saver of their souls. At one point, his voice and his granddaughter’s overlapped, the English and Spanish floating together, as the worshippers clapped their hands in response and the keyboardist played on.

After the sky went from pastel to dark, Moreno’s message ended, and people came to the altar to receive prayer. As the prayer teams and respondents gathered, one woman stood with them, crying as she raised her hands.

When the altar call ended, Kearney addressed the crowd, declining to do a benediction, he said, because he wanted the revival’s spirit to continue. He urged attendees to bring their friends and families to the next event.

“Thank you all so much for coming out,” he said, with Mejia repeating his words in Spanish. “Bless you.”

The crowd lingered, talking and embracing one another, as light continued to shine from the revival tent on the warm September night.

Questions to consider

Questions to consider

- When the two pastors met, they recognized that they had a unique opportunity to build something together. Are you open to opportunities that might come your way?

- Ruiz-Millán said that if Christians engage only with people like themselves, they have “an incomplete notion of who God is and what the Christian life is about.” In what ways could your congregation expand its notion of Christian life, and act upon it?

- Mejia said that when she interprets for others, she experiences God speaking through her. Are there ways in which you serve others that you could reframe as ministry?

- Kearney calls this partnership “traditionally innovative.” In what ways could you innovate on tradition in your context?

- Have you worshipped or sung in other languages? If not, what might you learn from that experience?