Lessons from pastors who have left parish ministry

The Rev. Afi Dobbins-Mays proved resilient amid adversity throughout her first pastorate, serving two rural United Methodist congregations outside Madison, Wisconsin. But in 2022, a decade later, no amount of grit could keep her in ministry. By then, she was demoralized and needed a change.

She had overcome racism, aimed at her as a Black woman, including when individuals in her nearly all-white congregation had repeatedly refused to meet with her. Congregants had rallied behind her, raised awareness of the issue and helped bring in a diverse group of new members.

“There was a beautiful culture in that church,” she said.

But then her conference relocated her to a “critical mission site” (i.e., not financially self-supporting) in inner-city Milwaukee, where the stressors were many and the supports few.

Half the congregation of 60 quit the church upon her arrival, unwilling to have a woman in the pulpit. Grant funding was promised but fell through, she said. And when regional United Methodist decision makers called during pandemic hard times, it wasn’t to show support.

“They said, ‘What’s the reason why your church is not financially solvent right now?’” she recalled. “‘Why is it that you guys aren’t on your feet?’ It felt like a punitive conversation. They started cutting the money back.”

What does rallying to support a pastor look like in your congregation?

When a second congregation was added to her Milwaukee charge, her pay remained the same: about $43,000 plus benefits. She informed her district superintendent that she needed to earn at least $60,000 plus benefits, she said, but was told that wouldn’t happen in Milwaukee or anywhere else.

“I started looking into other options, because I didn’t really see a viable pathway to grow in my career after that conversation,” Dobbins-Mays said. “I didn’t feel supported in ministry.”

She worked briefly for a food bank before accepting a three-year position as assistant to the bishop for authentic diversity and leadership in the Greater Milwaukee Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. She finds satisfaction now leading workshops on racism and oppression. And in a cause close to her heart, she’s helping launch a new ELCA camp next summer for children with an incarcerated parent.

Dobbins-Mays is one of a number of clergy who have left their jobs in parish ministry because of factors including managing institutional decline. And though there might not be a real “great resignation” of pastors, those like Dobbins-Mays can offer insights into the stressors affecting pastors in the U.S.

Expanding discontent among clergy surfaced in January when the Exploring the Pandemic Impact on Congregations (EPIC) study reported findings from a fall 2023 survey of 1,700 religious leaders. More than half (53%) said they’d seriously considered leaving pastoral ministry at least once since 2020. That’s up from 37% surveyed in 2021.

A closer look reveals that mainline clergy are the group most likely to consider leaving. Those particularly at risk include pastors serving congregations of 51 to 250 worship attendees with no ministry colleagues on staff; those in congregations that foresee struggling to survive — or closing — in the near future; those mired in congregational conflict; and those who say their congregations are unwilling to change to meet new challenges.

“The pandemic was a collective trauma both for the clergy and for the church,” said Scott Thumma, the director of the Hartford Institute for Religion Research (HIRR) and the principal researcher for the study. “Both of them suffered. And both of them, our research is showing, are collectively responsible for overcoming some of these challenges that lead to pastors thinking about changing congregations or leaving the ministry.”

The report is quick to add context to the percentage of pastors who have seriously considered leaving. Congregations are not seeing a collared exodus. Considering leaving and actually leaving are not the same thing. Numerous factors keep pastors in parish ministry, even if they’re not thrilled about it.

What are the stresses in your congregation? Who feels that stress most acutely?

“There’s not a spike in clergy retiring early or in their departure, at least through 2022, in the data from some of the denominations,” Thumma said in a webinar on the report. “I don’t think we’re going to see the ‘great resignation’ that many people have talked about.”

Nonetheless, those who have left in search of greener professional pastures might shed light on what needs fixing. That’s the expertise of Todd Ferguson, a Rice University sociologist of religion and co-author of “Stuck: Why Clergy Are Alienated From Their Calling, Congregation and Career … and What to Do About It.”

Ferguson names four factors that have led to a number of pastors leaving parish ministry: managing institutional decline; navigating conflict or division along political lines; feeling they couldn’t be their authentic selves in the congregational leader role; and facing disillusionment with a drifting mission.

A lack of resources

Demoralization doesn’t afflict just those who become burned out in ministry, as Dobbins-Mays did. Fallout from mainline decline is taking a toll also on people who still feel called but can’t make it work in today’s resource-constrained local settings.

Take the Rev. Loren Richmond Jr., a 41-year-old ordained minister in the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). Richmond reluctantly began transitioning out of parish ministry in 2021 when he took a full-time job in local government. He now works for the Aurora Housing Authority, where he coordinates services for elders and veterans.

Do you see the four factors Ferguson describes in your congregation?

“I needed to make more money,” Richmond says flatly. “I don’t know if it’s feasible financially [to do parish ministry], at least at this stage of my life. And that’s really hard for me. I’ve committed 20 years of my life to this.”

The numbers just weren’t working. Having bought an average-priced house for his family of four in the Denver metro area in 2021, when interest rates were still low, he’s now paying down a $3,000 per month mortgage. Even with his wife’s income, they couldn’t swing it on his $45,000 salary for a three-quarters-time associate pastor and youth director position. He now earns $61,000 plus benefits in his government job.

Who is responsible for identifying and deploying resources in your congregation? Is the duty shared?

His departure from ministry came despite creative attempts to keep pastoring. After starting his government job, he continued working at Washington Park United Methodist Church in Denver on a reduced, quarter-time basis (10 hours a week). Yet even with his church duties scaled back, he was constantly thinking about the next sermon or next youth activity, until he couldn’t do it anymore. He gave his final sermon Jan. 14, 2024.

“After eight hours of work and two hours in the car, there was not a lot of stamina left, even to sit at the computer and do something church related,” Richmond said, holding back tears in a Zoom interview. “That’s really what it came down to. I found myself out of gas, mentally exhausted trying to manage it all.”

Growing divisions and threatened authenticity

When Ferguson says pastors leave ministry to escape feeling trapped in a political tinderbox, he could be talking about the Rev. Christi Tennyson of St. Louis. She left ministry in 2021 to become a fundraiser for Presbyterian Children’s Homes and Services.

Now 48, she was first licensed to pastor in 2015 and has been ordained in the United Church of Christ since 2018. She says she became a progressive thinker while reading the Bible deeply for the first time at Eden Theological Seminary.

“I’m not going [to] preach politics, but what I would preach were Christian values,” Tennyson said. “I tell people, ‘The whole crux of every world religion is — I’m going to use a bad word — don’t be an a——.’”

Before the pandemic, her approach to politics and liberal theology wasn’t a problem at Pilgrim United Church of Christ, a purple, aging congregation of about 55 in rural Labadie, Missouri. They knew each other. Serving 19 hours a week in the parish, she’d joined them in mission projects, such as hosting bluegrass concerts and a huge Halloween festival every year.

“They were really good at mission in their tiny town,” she said. “I loved the people. I still love the people. I miss them.”

But the pandemic pushed them apart, literally and relationally. Worshipping solely on Zoom for a year created a chasm that never closed.

“I felt I had lost the connection to my people,” Tennyson said. “I’m a hugger, and when you’re just looking at people over a screen, you lose the conversations that tell you what’s happening in their lives.”

With relational ties weakened, political differences felt sharper as in-person activities resumed. She listened as parishioners expressed negative views of various types of people, including immigrants, high-profile rape victims and women who’d had abortions. She came to think her “love your neighbor” preaching wasn’t making a difference. Their values were too far apart.

“I just felt like, ‘What am I doing?’” she said. “They listen for an hour a week, and then they leave and they’re spewing hateful rhetoric. … It was soul crushing.”

Along the way, trying to be authentic and forthright without alienating conservatives was a never-ending concern. She felt she had to hide who she was: a self-described “foul-mouthed sorority girl” who’d once had an abortion that saved her life. Her flawed humanity was a strength in the pulpit, she said, but always having to walk the fine line of congregational diplomacy was “exhausting.”

“A lot of times, pastors are hamstrung, because if enough people don’t like what you say, you will lose your job,” she said. “There was always fear on some level that I would say the wrong thing and make the wrong person angry and I would lose the job.”

Feeling burned out, Tennyson didn’t consider moving to a new church, because by the time she left in 2021, parish ministry didn’t fit her life anymore. Her marriage was heading for divorce. She expected that another congregation would not accept the spiritual authority of a recently divorced woman. She also didn’t want to feel judged for dating. And then there was the matter of money. Becoming a single parent meant she needed to earn more, but most UCC parish ministry jobs in her area aren’t full-time with health benefits, she said.

Now a successful fundraiser, Tennyson feels called to her new vocation. She’s grateful that she can pray daily with colleagues and do something to make the world better. In her new role, she’s a frequent guest speaker in local churches but no longer bears the weight of churchgoers’ expectations. She appreciates not having to manage what she calls “the church nonsense.”

Disillusionment with mission drift

On paper, the senior pastor position that the Rev. Alexander Lang accepted in 2013 was a plum. He preached to more than 500 in weekly worship attendance, worked alongside 15 staff colleagues and oversaw a budget over $1 million at one of greater Chicago’s most prominent mainline churches, First Presbyterian Church of Arlington Heights.

When a pastor does leave your congregation, do leaders ask about the forces that contributed to the decision?

“I don’t think that I could have found anything better in terms of a church,” Lang said.

But Lang wasn’t getting to do what he entered ministry to do, which was to “build community and create the kingdom of God on earth,” he said. Instead, he was devoting half his time to fundraising, committee meetings and other institution-supporting endeavors. After 10 years, he left the position this past August.

“The church is not really a church anymore; you have to treat it like a business,” Lang said. “Which is unfortunate, because if I’d wanted to run a business, I would have gone to business school.”

Signs of decline, such as a 50% drop in worship attendance over his decade in Arlington Heights, only increased the pressure he felt to keep the institution afloat. Along with that came pressure to assuage demanding parishioners and sometimes endure what he regarded as emotional abuse.

“There were people who felt like, ‘Because I helped to pay your salary, I can treat you any way I want,’” Lang said. “They felt like they could berate me without any real thought to what that means to me as a person.”

Lang became convinced that he’d need to leave ministry in order to live out his vocation as a change agent. He’d tried on several fronts, from delivering provocative sermons to laying groundwork for new social enterprises. But the large-scale change that he believes is necessary was a tough sell.

Lang is now an aspiring tech entrepreneur, seeking angel funding for a product he isn’t discussing publicly. All he learned about business in the church might be transferable to his new venture. At least that’s the hope.

Thumma, drawing on his research, has some advice for congregations hoping to keep their pastors from leaving ministry. First, he says, churches and clergy need to recognize that the last four years have been traumatic and the effects are still being worked out. Second, churches should try to find ways to reduce levels of conflict and find ways to appreciate the relationship between the clergyperson and the congregation.

“It’s pretty clear what creates a hospitable environment and reality for a flourishing congregation and what doesn’t,” Thumma said. The challenge is that it requires working constructively together.

The recent HIRR report said it well: “What is positively associated with fewer thoughts of leaving is … being in a church with a bright outlook for the future, one that has less conflict, is more open to change and adaptation, and cultivates a good, healthy [relationship] between the members and pastor.”

Who are the hopeful people in your congregation and community? How can their voices and influence be strengthened?

Questions to consider

- What does rallying to support a pastor look like in your congregation?

- What are the stresses in your congregation? Who feels that stress most acutely?

- A Rice University sociologist has identified four factors that push pastors to leave parish ministry. Do you see these factors in your congregation?

- Who is responsible for identifying and deploying resources in your congregation? Is the duty shared?

- When a pastor does leave your congregation, do leaders ask about the forces that contributed to the decision?

- Who are the hopeful people in your congregation and community? How can their voices and influence be strengthened?

When Jack Causey moved to a neighboring city to pastor their First Baptist church, I waited for a couple of months and then called.

“You don’t know me, but I know you. Could we meet?”

It sounds like a note passed in middle school, but we were adults. I was a pastor in my 20s in need of guidance. Jack was entering his fourth pastorate. Each congregation had thrived under his leadership.

Jack’s preaching and worship skills were such that he frequently designed worship services for and spoke at youth events and on college campuses, which were then tough crowds. Jack had been the pastor-adviser to a campus group when I was an undergraduate. I did not know him personally, but I was part of the crowd that followed him.

At lunch, I mentioned needing to learn from him, and Jack immediately rejected the idea of being a mentor or coach. We could be friends and peer pastors, he said. He was willing to meet once a month. We did that for about five years. Later, Jack agreed to facilitate an intensive, yearlong leadership development group with me. We did that for a decade.

Jack died in November, 37 years after our first lunch. On Facebook, because that is the social media of my generation, I read hundreds of clergy testifying to Jack’s impact on their lives. At his memorial services, I learned that Jack had gathered peer groups before that phrase was known in our denomination.

I wondered: What was so special about Jack Causey? How did he come to influence so many people?

When I asked to meet with him in 1986, I was drawn to his skills as a storyteller and his experience as a pastor. After years of facilitating groups with Jack, I realized that his superpower was listening.

Everything from the intense gaze of his blue eyes to the forward lean of his posture communicated that he heard me. If he knew something that would help, he would offer it. If not, he would give enough feedback to demonstrate that he was hearing me and was with me. Person after person in the memorial service testified to receiving the gift of being heard.

One of the reasons Jack resisted the title “mentor” and was hesitant about being a “coach” is that he was humble. He thought those titles suggested that he had some technique or wisdom. He would say he offered kindness. He offered friendship.

That description might suggest that he was passive, but Jack had a keen sense of how to put what he was hearing and noticing into action. As a congregational pastor and elected official in his denomination, he honed the skills of good leadership. He moved toward conflict and sought productive resolutions. He worked to establish consensus and held himself and others accountable to goals.

He was a master at setting and keeping boundaries. Before smartphones, Jack never carried his calendar with him, because he wanted to have space to think through any commitments being asked of him. At the church, the only key that he claimed to carry was to his office. He did not want to be distracted by being drawn into doing others’ work. At our first lunch, he set a rule that we would each buy our own meals (although when I was his “boss,” he did let me pay).

His leadership and service engendered long-lasting loyalty. A couple of years ago, I arranged to visit Jack. That morning, I learned that his beloved wife, Mary Lib, was gravely ill and had been admitted to hospice that day. Jack wanted me to come to the hospice house.

When I arrived and asked a volunteer to be directed to Mary Lib’s room, the lobby quickly filled with six or seven more volunteers. They asked all sorts of polite questions about how I knew Mary Lib and Jack. I was from out of town, and they were determined to protect the Causeys at this vulnerable time.

Jack heard the ruckus and came out to assure the group that we were old friends. I was deeply moved by the mutual care that had developed between the Causey family and the community and had endured for more than 20 years after his retirement from First Baptist.

After I left the pastorate near Jack, I launched a center to support congregations and established a leadership development program for clergy in their first five years of congregational ministry. Another mentor of mine guided me in setting up the framework to serve about a dozen clergy per cohort. I was near the same age and experience level as the participants and needed a partner who could bring decades of experience to the program in a humble and inviting way.

I approached Jack, and we co-led the yearlong program for about a decade. A few years into that process, Jack retired from the pastorate and devoted his vocational energy to staying in touch with the participants. Over time, the participants spread the word about how helpful a conversation with Jack could be.

My contribution to Jack’s post-congregational ministry was to create conditions for him to offer friendship and encouragement to more pastors. Jack knew this was his calling, and he asked me how he could do it in an accountable way. Eventually, our denomination also set up a structure for Jack’s work. When I read all those Facebook posts and comments, I took some comfort in knowing that our institution and denomination had been part of creating the opportunity for Jack to befriend more people.

Jack Causey’s ministry reminds me of the impact that happens when someone is committed to what Jack called friendship and I know as mentoring. It can happen one-on-one through the individual’s initiative. The impact can be expanded by thoughtfully created structures and conditions. But at the heart of it is a person deeply committed to careful listening and mutual respect.

Jack may be right that “mentor” is not a helpful word, because it commonly represents a top-down relationship. But he brought wisdom to our relationship and to countless others that many in my denomination will miss.

Thanks be to God for Jack. May we all be inspired to offer friendship to colleagues after his example.

Brian Ide is on the road. He’s somewhere between Flagstaff and Albuquerque, headed to Amarillo and points beyond, traveling cross-country to talk about a topic that, in this moment, feels both vitally important and virtually impossible to achieve.

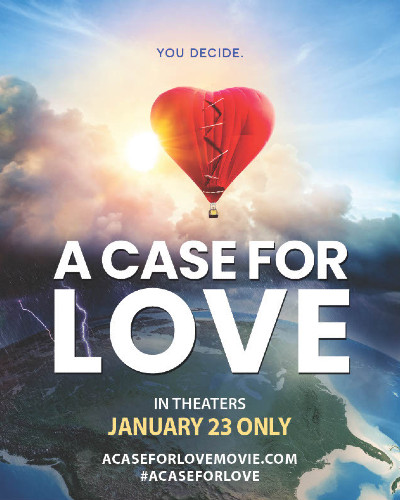

In his new documentary, “A Case for Love,” Ide raises the possibility that unselfish love could be a bridge across the nation’s significant social and political divides.

The topic plays out through conversations — some with people the film’s crew literally walked up to on streets across America, others with individuals and families deeply engaged in living out love through challenging situations. And there are interviews with recognizable figures such as Al Roker, the Rev. Becca Stevens and Presiding Bishop Michael Curry.

The son of a Lutheran pastor father and Catholic mother, Ide has worked in the entertainment industry for more than two decades, founding Grace-Based Films in order to start telling faith-centric stories that weren’t being told in Hollywood. He had joined the vestry as a parishioner at All Saints’ Episcopal Church in Beverly Hills and quickly recognized that conversations about stewardship and pledging shortfalls did not play to his strengths.

“It could be a long [vestry term] — or maybe we could start telling stories and utilizing other gifts in our parish because of where we were,” Ide said he thought. “Especially back then, [what] was coming through Hollywood was centered around, if your faith was strong enough, then your football team won and your marriage was reconciled.

“We thought, ‘Who’s telling the stories about the messier, more complicated conversations, where you don’t get the big football win?’ It was born out of there.”

“A Case for Love” is Ide’s fifth film and first full-length documentary and will be showing in wide theatrical release for one day, Jan. 23. Ide spoke with Faith & Leadership’s Aleta Payne during a promotional tour. The following is an edited transcript.

Faith & Leadership: There are a lot of entry points into the conversations featured in the movie, including for people who are not from a faith background. Was that intentional?

Brian Ide: That was really important to us. Through the course of the filming, we had one story that was inside a church, because the story itself was about somebody’s faith journey. Then Al Roker, when he agreed to do a cameo for it, wanted it to be at St. James’ [Episcopal Church], but other than that, it is a story about ordinary people.

It is not a propaganda machine for the Episcopal Church or for the Christian church. It’s not a story about telling you what to believe on any of these entry points that you’re talking about; we are not experts on anything. It is truly a journey story about bringing human beings back together again in a time when it feels like we’re all being pulled apart. What can we take from being exposed to people’s intimate, vulnerable stories? We were really intentional about not hiding from it but also trying to do something that had a broad reach.

F&L: You feature such a breadth of people. How did you find and choose them?

BI: The film itself is broken into four groups of people, and the bulk of it, probably 95% of the whole film, are these deep-dive stories of ordinary people that cover a range of topics that are woven together into seven chapters. It’s usually two, maybe three of these stories woven into a single chapter, and the chapter itself has a universal theme — so a chapter on love and loss or a chapter on being dealt a difficult hand or a chapter on answering the call.

We knew early on it was really important that the bulk of the film be about ordinary people, because we wanted it to be for ordinary people so that, hopefully, they’d be inspired or moved or motivated to do something in their own life. If they see it’s Bob and Susan doing this, then they’re like, “OK, well then I think I can do that.”

Whereas if all we had was a bunch of CEOs and Mother Teresas, it would be, “Great for them, but I’ll never do that.” So that was really intentional; that’s really the heart of the film.

There were a handful of those that we had lined up before we started the filming tour, and two of them were military. We knew that it was important for us to explore the military space and that intersection of what we assume is this community that has to face conflict and war and death sometimes, and how does that intersect with love. We were just fascinated by the power of that.

Beyond the four or five we originally had lined up, it was trusting in the Holy Spirit to start in Minneapolis and be with people. And they’re like, “You’re going to Indianapolis? Listen, you really need to meet with Tim Shaw. Let me see if I can make that happen.” And the rest of the stories ended up coming from the journey itself revealing [them].

It was this mix of being intentional and planning about having diversity in the stories but then letting the Spirit guide. I love that, because we ended up being with the people that we were supposed to be with, and they weren’t people that were chosen because they’re experts on any of these topics; they’re just people. We’re in their homes, and we’re creating a space that’s vulnerable enough and safe enough for them to open up about their particular journey.

That’s the deep-dive portion of it. Then we were fortunate enough to have access to these notable figures, and those were politicians and actors and rabbis and Muslim leaders and NGO leaders. That helps Hollywood see that they can have something to sell a ticket on, when you have these notable faces and names in there.

The third group are people on the streets. We had probably 200, 250 of those, where we just pulled over [and approached them] everywhere, from downtown Indianapolis to the Brooklyn Bridge to just a small row of farms in Pennsylvania. We would just pull over and then walk up to people and ask them about what comes to mind when they hear the words “unselfish love,” and where have they seen it in the world and where have they seen the absence. Those were probably the interviews I enjoyed the most, because of how eclectic they were, how surprising they were.

After all of that, we sat down with Bishop Curry and said, “OK, you’re the teacher. Here’s what we saw. What does this mean?” He’s just beautiful about speaking to the human condition.

F&L: What a faithful way to have set out to do this, to discover the voices you needed along the way.

BI: I would say that. Or terrifying. One of those two. I think it’s a little bit of both. But it was a trust, which I loved.

F&L: What surprised you or resonated with you from these conversations?

BI: A couple of things. This first one wouldn’t be a surprise but would be a reinforcement for me that we are way more connected than the headlines of the world want us to believe.

Most of us are trying to figure out how to take care of our families and loved ones; most of us are trying to figure out what our purpose is on this planet; most of us are trying to figure out how to be kind. And most of us find that pretty tough at times. In being with people and talking about those things, where we were on some political issue or social issue never came up. Just the human part of the dialogue came up. It reminded me and reinforced for me — and that gave me hope — that we are very much connected.

The surprise part of the journey was probably the people-on-the-street times, because we’re a crew of eight. It’s a big camera package. We have big sound equipment and all of this. When you walk up to somebody and they’re walking to the grocery store to get their lunch and you pull them aside, I think everybody’s first sense was skepticism.

The surprise of it was that as soon as they believed what we were about, then there was this lifting of spirit across the board and there was a sense of, “You want to know what I think? Nobody ever asked me what I think about that and holds that in value.”

I saw that time and time again. When that happened, they shared incredibly beautiful, vulnerable, intimate things that they probably never in a million years imagined they would tell a group of strangers on camera on their way to work.

That surprised me, not knowing what that part of the process would be like, and I think that’s probably why I enjoyed them so much.

F&L: You talked to children and to young people and gave value to their stories as well.

BI: What I loved about the young people is they don’t tell you as quickly what they think you want to hear — they tell you what they think. That gives me hope too, because we’re all born with a pretty good soul and a pretty good view of what love is and instincts of what love is. To sit with them reinforced that.

I think the next project is going to be centered around young people in some way. I think, this last handful of years, that they’re absorbing toxicity at a rate that we’re not fully aware of, and I think that they’re struggling in a variety of ways. So I want to do something to serve them.

We had a national educator see one of the screenings of the film. He was like, “Can I create a discussion guide that uses our language in schools for young people?” He created a free one for seventh through 12th graders (it’s on the website and free to download) that uses the language of young people and educators. That was a beautiful thing.

F&L: Where do you hope to go with this particular project, and what’s next for Grace-Based Films?

BI: For this one, Hollywood is in an enormous period of transition right now, and I think they’re trying to figure out what models are working and not working. Is it streaming? Is it not streaming? What kinds of movies do they greenlight?

For films like these, they don’t usually get significant platforms. And when they do get platforms for faith-centric movies, historically, a lot of them have been catered to big evangelical megachurch worlds.

It’s much harder in the Episcopal, Presbyterian, Lutheran worlds to do that, so they just haven’t been given the megaphone in that way. It is really important to me to do everything we can to show the business analytics side of this, that there is an audience for these stories.

We were offered this theatrical release, which is in almost 1,000 theaters nationwide, provided by Fathom Events. (Fathom is owned by AMC, Regal and Cinemark.)

They created this company to create opportunities to add new content to midweek auditoriums and theaters, because most of their box office happens on weekends. They can now offer it to films that aren’t “The Avengers” and “Avatar” and give them opportunities like this.

The way it’ll work for us is that we’re in theaters on Jan. 23 for one day only, as most of their films are. We push all the attention toward that, and the success of the attendance and engagement with that will then dictate, “OK, does that mean that Netflix is next or Amazon is next or Peacock? What streaming opportunities? What opportunities are there for military bases?”

All of those have this tiered downstream process dictated by Hollywood. Much of that will be on the success of Jan. 23.

I try to plan for the next one, and I realize, every time I do, that I’m wrong. But I really do feel this pulling toward something that is youthful. I want to travel again and spend time with [young people] and listen for, like, “OK, what are the things that you all are talking about, and what are you not hearing, and what are you not saying?” and then mirror that with the power of storytelling, probably in a scripted movie, not in a documentary. To find something in that space is where my heart is right now.

F&L: You address head-on that some people might view this movie cynically. Bishop Curry says in the film, “Someone could say that’s naive, but sometimes what we call naivete actually are ideals we don’t want to deal with.” Could you speak to that as a filmmaker?

BI: As we were in the earliest processes of dreaming this up, I was sitting with a writer-producer friend of mine who’s done this for a long time in Hollywood, and he said, “OK, here’s the deal. You have a documentary about love. You have an older, ordained minister as the inspiration for it. The vast majority of people are going to look at that and be like, ‘I already know what that is. I don’t need to watch it.’ Or some people will be like, ‘I want that,’ but they’re going to assume that they already know what it is.

“Your job as a filmmaker is to say, ‘You thought it was this? It’s actually this.’” That drove so much of the way I went about this process, and Bishop Curry was really focused on that as well.

He says it over and over again when I’m with him, and I’ve heard him say it to many other people too, that this is not a sentimental love. He said, “What I’m talking about is not sentimentality. Unselfish love is a very different thing.”

When you hear “unselfish love,” it forces you to take a beat, because you don’t usually hear those two words together.

Sometimes jarring people can be good. There are going to be some stories that are jarring. We have some really beautiful, simple, heartwarming stories in there, and then we also have a story of a woman who was sexually trafficked from the time she was 5. We have the whole gamut in there, because different people need to hear different things, and also to remind us that these are complicated things.

All of those things drove how we go about this, so it doesn’t get written off as a churchy thing or a Valentine’s Day thing but instead is like, “No, we really need to have these conversations as a human being thing.”

We’re seeing the effect of not having these conversations, and it’s not great. Those were driving forces for us.

F&L: What haven’t I asked?

BI: I’m a hopeful person. This film is funded entirely by donors across the United States, from individuals to foundations to parishes to all kinds of people. I don’t own any of the profits from it. Bishop Curry doesn’t own any of the profits from it. The people that funded it don’t own any of the profits. They all go toward telling stories that serve people. I’d love for that to come across. Because sometimes, I think, in the cynical world that we’re living in, it’s like, “OK, is this guy hopping around all over the place trying to get people to buy his product so his product is successful and he becomes successful?”

It is important to me that people know that that’s not the driving force of why we or the people that funded this made it happen. I do like sharing that, and I think people will be surprised — I think they’ll be moved by this.

We didn’t want people to go to a theater or watch it at home for two hours, be entertained or be moved, and then go back to their life. We wanted this to instigate something; it’s part of the launch of 30 days of unselfish love. So the call people will hear in movie theaters on the 23rd, the call is, when you go home, for the next 30 days, be intentional about seeking out — every day — some act that works in your world of unselfish love and journal about that. What is the impact on you, and what did that mean to you?

There are journals on the website too. They’re beautifully designed, and they’re free; they’re downloadable. Our CFO was the one who came up with this, and he’s a very Type A, analytical, list-driven person. He started this, and he put it on his whiteboard each morning.

What he found was that by the sixth day, it became a habit. Our belief is that acts turn into habits and habits create change. We invite people to use this and then find out whatever [is next]. A lot of the NGO partners — folks that are doing really great work that have come on board, like kindness.org, dosomething.org, racial justice programs and neighborhood collaboration programs — if somebody’s moved by the faith element of this, if they’re moved by the volunteerism element of this, here are groups that do that really well.

Take this as an instigator toward action. We hope that people see that too — that this is more than just a moment in time.

Recent research released by Barna Group reveals a demographic trend that may not bode well for the stability of congregations. As a significant percentage of pastors near retirement, the pipeline of younger successors appears insufficient to take over their leadership responsibilities.

According to the 2022 Barna Resilient Pastor research, one-quarter of pastors said they hoped to retire within the next seven years.

In addition, the age of pastors in America has been trending upward for decades. According to the 2020 Faith Communities Today (FACT) study, the average age of religious leaders has increased from 50 in 2000 to 57 in 2020. A 2017 Barna study found that the median age of a Protestant pastor was 54 at that time — up from 44 in 1992.

“As a generation of clergy ages and prepares to step down, it is not clear that churches are prepared for the transition,” Barna reported. “If this trend goes unaddressed, the Church in the U.S. will face a real succession crisis.”

According to Ashley Ekmay, a lead researcher for Barna, one of the most significant questions arising from the study is whether pastors are exhibiting to younger people that entering the ministry is worth it. “The data seems to indicate that the answer to that question is no,” she said.

Much of that sentiment can be attributed to the fact that a rising number of pastors are considering quitting themselves — and not just to retire. “As of March 2022, 42% of pastors said that they had considered quitting full-time ministry in the last year,” Ekmay said. “That is a very jarring thing to state.”

Numerous factors seem to be contributing to pastors’ current state of mind about leaving the ministry, Ekmay said.

“There’s this collective ache among pastors,” she said. “When we asked them about burnout and whether they were considering quitting in 2022, they pointed to numerous things that were making them feel that way. Divisions in the church were a huge factor, especially from increasing polarization in America coming off George Floyd’s death, masking during COVID and Trump’s presidency.

“The pastors felt like they had to take a side, but no matter what side they picked, they were on the wrong side,” Ekmay said.

When addressing succession planning for the church, Barna found that 38% of 584 pastors surveyed personally made it a top priority to equip, nurture and identify leaders to take over their role upon retirement. However, nearly an equal number of pastors — 40% — indicated they had “thought about the need but have too many other ministry concerns.”

Whether or not they had invested in succession planning, a significant number of pastors responding to the Barna study said they anticipated difficulties in finding younger successors. As of 2022, only 16% of Protestant senior pastors were 40 or younger.

According to the survey, which was conducted in September 2022, 75% of pastors said they “strongly” or “somewhat” agreed with the statement “It is becoming harder to find mature young Christians who want to become pastors.” Nearly 35% of the respondents strongly agreed with that statement — up from 24% in 2015. More than 70% of the pastors also said they strongly or somewhat agreed with the statement “I am concerned about the quality of future Christian leaders.”

More recent pastor interviews related to Barna’s research series seem to indicate that the succession challenge may not be going away anytime soon. An additional factor seems to be emerging, suggested by the early findings of the 2023 study, which is scheduled to be released in spring 2024, Ekmay said.

“We’ve noticed that there seems to be a contagion effect,” Ekmay said. “When we asked, ‘Do you know anyone else who has quit the ministry?’ we found that those who knew someone who had left were giving more thought to leaving themselves.”