‘On Becoming Wise Together: Learning and Leading in the City’

This book reframes traditional Euro-North American conceptions of theological education by reflecting critically on my lived experience as a British-born Chinese-North American woman, a family member, an immigrant, an urban theological educator, a maker, a gallery curator, a community gardener, a Girl Scout troop leader, and a scholar. It is not limited to the context of formal institutions recognized as places where theological education happens, nor the content of a seminary curriculum as philosopher and theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher might have designed it in nineteenth-century Germany. It reimagines theological formation for the many together rather than the individual alone, and as happening in a wide range of times, spaces, and places.

I propose here that intercultural and communal understandings of theological teaching and learning suit the context of a complex and quickly changing urban world better than individualistic, rational Western habits of knowing. We are in the midst of a moment in which the reemergence of a model of collective wisdom is challenging the expert-knowledge approach that is bolstered by an information economy and capitalism. Traditional forms of theological education built out of a particular cultural and historical paradigm to educate individual, and usually male, ordained clergy are no longer relevant, accessible, nor sustainable; this is evidenced by multiple national studies on the decline of the North American church, diminishing student numbers, and increasing financial instability of theological institutions. The entire ecosystem of theological education is grappling with the need to reexamine systems and structures and innovate new “pathways to tomorrow.”

Now, how and where we come to know and with whom we come to know are as important as what we know. We are learning again how to learn. Rather than receiving inherited knowledge, we are expanding sources and means of understanding and being; we are living theology as a verb.

This collaborative approach to cultivating wisdom has some resonance with the early church. In Acts 1:12-14, when the apostles and others were sent back to Jerusalem to await direction after Christ’s return to heaven, they gathered together, prayed, and waited. The Pentecost was a spiritual and physically embodied event that included the sound “of a violent wind” that came from heaven and “tongues of fire” that came to rest on each of them. The filling of the Holy Spirit led to the powerful testimony of Christ’s reality and good news, in every language of those present.

From there, a crucial decision was made in Acts 15 after much discussion and discernment through the Holy Spirit, namely, that the church need not be culturally homogeneous. Rather, the church was for the Jew and the gentile. It was together that the church waited in order to become wise.

In our own contemporary time of uncertainty and unraveling, we too are waiting, waiting for the wisdom needed for this turbulent age. We as a world Christian church can come together around what Latina theologian Elizabeth Conde-Frazier calls la mesa. This is not simply to redistribute power and resources from a historical center to the margins (presuming there even is a legitimate center) and to confront a legacy of structural and systemic racism in institutions and communities. It is an opportunity to witness a rearrangement of locations, a remapping of plural centers of power and margins of possibility.

The late African American writer bell hooks describes the margin as “a profound edge. Locating oneself there is difficult yet necessary. It is not a ‘safe’ place. One is always at risk. One needs a community of resistance.” By embracing the tension of writing out of the margin, from who and where I am, this work performs an alternative, aesthetic, oppositional act of becoming, of creating space to see differently and make meaning. It is a book I write to remember, to rehearse, and to map out what God has done in places where I come from, where I have been, and where I am going with others, with my “community of resistance.” This is not simply nostalgia, as bell hooks points out; it is a “remembering that serves to illuminate and transform the present.” I take time to pause, reflect, and connect the dots of seemingly disparate stories that show how God is at work in my life.

In listening to and sharing stories of coming together around la mesa, we encounter the possibility to engage a complexity of kinds of knowledge and approaches to wisdom. Through such coming together as the diverse but unified body of Christ, we can enter a liminal space between what is familiar and what is unknown. This is true for theological education as it has been described, and for our world more broadly, in these times between the times.

The late Scottish missiologist Andrew F. Walls suggests that through such necessary coming together we are returning to an “Ephesian moment” in our day, a moment in which our global urban world reflects an even greater diversity than in the early days of the church of what it means to be “Christian.” The reality is that we need each other now more than ever. “The very height of Christ’s full stature is reached only by the coming together of the different cultural entities into the body of Christ. Only ‘together,’ not on our own, can we reach his full stature,” notes Walls. This reimagining and reorientation take the form of the church flourishing in its diversity and becoming God’s shalom together in the city as family, friends, learners, and leaders. God’s shalom is found in the reconciling of God’s creation to right relationships with God, self, the other, and the natural and spiritual realms.

If, as Walls suggests, “the purpose of theology is to make or clarify Christian choices,” and if this attempt to think in a Christian way comes from within particular contexts and cultures, and in interaction with the Bible, then we are asking new questions every day. We are converting the material of life toward Christ through this Spirit-informed creative process that involves thinking, feeling, and acting. Yet will the church in all its diversity “demonstrate its unity by the interactive participation of all its culture-specific segments, the interactive participation that is to be expected in a functioning body? … Will the body of Christ be realized or fractured in this new Ephesian moment?”

As it did in the early days of Acts when practices of radical hospitality challenged the intersectionally compounded boundaries of class, gender, law, and tradition, so today the physical and spiritual realization of the body of Christ has theological, social, and economic consequences. The implications are ever present in intensified moments of pandemic, protest, increased racism and violence, globalization, and climate change. The invitation is to embrace being a part of Christ’s body while moving with others toward completion. In this movement, we need the generative work of the Holy Spirit to take action in us.

Excerpted from “On Becoming Wise Together: Learning and Leading in the City,” by Maria Liu Wong ©2023 (Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.). Reprinted by permission of the publisher.

The entire ecosystem of theological education is grappling with the need to reexamine systems and structures and innovate new ‘pathways to tomorrow.’

Low-status neighborhoods need talent retention. Instead, what they get is talent extraction, says Majora Carter.

“You are led to believe you need to leave — you need to measure success by how far you get away from there,” said Carter, a real estate developer and consultant who does work in her hometown neighborhood of Hunts Point in the South Bronx.

Carter, whose own family has experienced some of the ill effects of gentrification and predatory practices, has dedicated her efforts to building up her neighborhood and others.

Her projects include a local park and a coffee shop. In 2001, she founded Sustainable South Bronx, which aims to “achieve environmental justice through economically sustainable projects informed by community needs.” She also co-founded the Southern Bronx River Watershed Alliance and has been involved in numerous environmental and green jobs initiatives.

Carter wrote the book “Reclaiming Your Community: You Don’t Have to Move Out of Your Neighborhood to Live in a Better One” — which was endorsed by Lin-Manuel Miranda and Seth Godin — and gave a 2022 TED Talk on the same theme.

She is president of the Majora Carter Group, which offers consulting services in environmental assessment, compliance and planning. She has received many awards, including a 2005 MacArthur Foundation “genius grant” that described her as “a relentless and charismatic urban strategist” and New York University’s Martin Luther King Jr. Award for Humanitarian Service.

She spoke with Faith & Leadership’s Sally Hicks about her work in the South Bronx. The following is an edited transcript.

Faith & Leadership: Talk a little bit about the neighborhoods you work in and write about. You use the term “low-status” rather than more typical descriptors, and you actually begin your book with a glossary. Why?

Majora Carter: Most folks, when they use “poor” or “underprivileged” or “underresourced,” blah, blah, blah — it implies poverty is there. “Low-status” implies something much larger and deeper is at work. There’s a high status and there’s a lower status, and inequality is simply assumed.

It’s the places where the health outcomes are lower, where the educational attainment is lower. Yes, poverty exists more frequently in those areas as well, and there’s often a lack of hope in terms of the future of the community, both for people in the neighborhood and outside it.

And it can be anywhere. Urban, rural, suburban. It can be inner cities, Native American reservations, white towns where there was some industry and it’s long gone.

What we see happening all the time is that the bright kids, the ones who are academically or artistically or even athletically inclined, are led to believe that they need to grow up and get out of those neighborhoods. That’s really the underlying thing that just everybody gets. I don’t care where they’re from.

That’s why our approach to community development is a talent retention strategy, really.

F&L: Part of this mindset is what you call the perception of “poverty as a cultural attribute.” The community can’t change — it isn’t changeable — and therefore the only solution is leaving.

MC: It’s baked in, this idea that poverty is part of the culture. So that’s what you plan for, whether you’re an elected planner, whether you’re an elected official or part of the “nonprofit industrial complex.” That is what you’re planning for.

There are several industries essentially that profit off that, and that’s what we’re trying to work against.

F&L: You use the term “nonprofit industrial complex.” What’s your critique of investment done according to traditional means?

MC: It’s a structure that was designed to take care of needs. But if we understand that and then we look at the money that’s being spent and we don’t see that the amount of money we spend is actually reducing all those social ills, then you kind of have to wonder, “Is it working?”

I’m not saying that [the nonprofit sector] doesn’t play a great role. It does. I’m just saying let’s just ask that question. Stop doing the exact same things over and over and over again.

Huge amounts of government-subsidized affordable housing [are built] for the lowest income bands. You’re not building economic diversity in any of the housing.

Health conditions happen because of the environmental abuses in the same neighborhoods, and we don’t address any of the underlying things but are managing the health conditions that are here, whether they’re diabetes, obesity, heart conditions. Then we are surprised that those numbers stay the same?

We all seem to be surprised every single year. It’s mind-boggling to me. I know I’m not the only person who sees this.

We’re managing poverty. We have plenty of systems to manage people and their poverty. It’s an incredibly paternalistic system that definitely has its roots in white supremacy that says, “You really will never be better, so we’re going to help you — not that much, but just enough.”

We keep seeing that over and over again, and yes, it does bother me very much.

F&L: What have you done in your own neighborhood, and what were you trying to accomplish with your projects?

MC: Ultimately, what I try to do is to help folks in my community, and communities like it, to not believe the narrative that our communities are places that are meant to be escaped from. We actually do have the capacity to revitalize our community from the inside out.

It started in my early work, when I was in the nonprofit sector for a number of years. I’ve always done project-based community development, because I’ve always felt the people needed to see and experience something different from what only screams poverty.

Again, the environment of our neighborhood literally often does say that. People know they need to leave their neighborhood in order to experience a nice park or a decent supermarket or a nice place to have a cocktail or a coffee with their friends.

What does it say about where you’re from? It says, “You don’t really need to be here if you have any sense of aspiration for yourself.” And most people do.

What I’ve tried to show is that we have wonderful things to offer people within our neighborhoods. The projects range from spearheading the development of the first waterfront park our neighborhood’s had in over 60 years. It was the only park — waterfront or not — that actually had grass and trees and the kind of places that made people feel, “Oh wait, this is a really special place to be.”

Then we did some work where we helped people have both a personal and a financial stake in the improvement of their environment. So we’ve created green-collar job training and placement systems.

F&L: Tell me about the cafe; that you’re sitting in right now while we’re talking on Zoom.

MC: In the early days, our work was more focused on consulting, but then it didn’t take us long to realize that it was really real estate development that we needed to be focused on.

We started in small multifamily [housing], and then we realized the other piece was lifestyle infrastructure. In part, we did that because it was nearly impossible for us to get the kind of financing that we needed to do larger projects. I didn’t really know much about real estate development, frankly, at the time.

But when we realized that what people were leaving the neighborhood to experience was places like cafes and coffee shops and things of that nature, we actually sort of used our own good credit. We made relationships with some of the local landowners that had businesses and got very, very reasonable rents on a couple of spaces in the commercial storefronts of their buildings.

We really wanted a cafe, because, again, we did an enormous amount of market research in the form of surveys and focus groups to understand what was it that made people feel good about being in their own neighborhood or not. Why were they leaving the neighborhood to experience something good?

So we got a lease, and we realized that most of the folks who wanted to build a cafe did not have the capacity to do it. We went to Starbucks, actually, and they were just like, “Nah. Your market is too emerging.”

That was really hard to hear, but then we ended up partnering with this awesome group called Birch Coffee, and we did a joint venture with them to open up our very first coffee shop. But it was also clear that we needed to be more about our own culture from the cafe’s perspective, and so that’s why we branched off into the Boogie Down Grind Café [in 2017] and rebranded ourselves.

It’s like an homage to hip-hop. Where I’m sitting right now, you take off the cushion and it becomes a stage, with a great big plate-glass window behind me so people can see it, for open mics or all sorts of wonderful things.

The day we were protested, we were hosting a workshop in this space for people who wanted low and 0% interest loans for either homeownership or for business development. It was kind of tragic and sad but ironic. But that’s what we did.

But those types of things — building out a space so that the community could come in and fill it and be seen in a cool place where people felt really good about how they looked — it was really fun, and we had a really nice time with it.

F&L: You mentioned a protest. You’ve gotten recognition for but also criticism of your work. Why do you think that is?

MC: Because Black girls from neighborhoods like this are not supposed to do this. I am acting way above my station, and I’m not supposed to do it.

We are just so duped into this idea that the only thing we can really be is just managed where we are, and that’s why [the detractors] behave that way.

I don’t know what they thought or what they think they’re getting out of it, but I no longer wish to continue to allow the idea that only a few companies around the country, in any city that you’re in, are the only ones. They’re almost always led by white men.

That’s why our communities are the way they are. I don’t feel that’s the only way our communities can develop — and why don’t we have that conversation?

But yeah, being a Black woman just paints another target on my head from everybody concerned.

F&L: I wanted to ask you just to clarify one thing. Several times you’ve said, “We did this. We did that.” When you refer to the “we,” are you referring to a development company?

MC: My company, yes. It’s interesting that I get that question. I really do think that it’s still hard for people to believe that I do this as a Black woman from a neighborhood like this. Of course I have a company. It’s small, but of course I have a company. I’m long on vision and short on balance sheet, but even functioning in that way, it’s still us, still doing the work of a developer.

F&L: What projects are you working on now?

MC: We’re redeveloping a commercial property, which is a former rail station. It’s a feasibility study to do an assemblage, which would be roughly 1,000 units of mixed-income housing, including homeownership, and about 400,000 to 500,000 square feet of manufacturing and commercial space.

That’s my dream. Literally, I want to be able to co-lead that project, and then I’ll retire. I will show that it can be done by someone who looks like me, and then I’ll walk. That is my prayer. Because I’m just too old. I’m going to be 60 in a few years, and I’m done. I’m not going to lie.

F&L: Even on Zoom, you do not look like someone who’s talking about retirement.

MC: Oh no, I am. I swear I’ve aged a lot over these past few years. I’m grateful. I know I’m blessed that I have the ability to do what I do. I’m still here, despite being smacked around as much as I’ve been. I can still smile and laugh about most of it — it makes me super, super happy — so that’s great.

F&L: If a congregation wants to do this kind of work, what would you recommend? I know you’ve worked with the Parish Collective organization.

MC: I was at the last Parish Collective [event]. I had actually been talking to a lot of them about, “What are the roles churches can play in development?”

If they do have property, how are they using it to support folks? More economically diverse communities are actually safer economically, socially. Spiritually as well.

But also really paying attention to predatory speculation. How do we support the homeowners that are already in those communities to keep them from falling victim to predators? I think churches can play a huge role in that, and so some of us are actually starting to have those conversations around it, which is great.

F&L: Do you come from a faith background?

MC: No, no. I am a Christian, definitely a follower. [But] I didn’t become a Christian until years later. I do feel like this is my ministry. And my ability to love my neighbor — I feel like this is my contribution. This is how I can give, and I love it.

Pastors and my garden plants could have a lot in common, to the benefit of the clergy.

This occurred to me recently when a denominational leader lamented that pastors feel they are unable to be vulnerable in denominational spaces. The denomination supervises too many elements of pastors’ professional lives for it to be a safe space for mental and spiritual health conversations.

No single organization can provide pastoral leaders with all of the support they need. Instead, pastors need a network of institutions committed in distinct but collaborative ways to their thriving.

As with clergy, my garden plants need more than a variety of components in their soil to grow; they need a network that shares these resources effectively and collaboratively. Front yard gardening — a high-maintenance and high-reward hobby — has provided me with a window into how plants network.

I didn’t set out to turn my entire front yard into a garden. I started with a 4-by-4-foot raised bed to grow some cherry tomatoes and basil. Seven years later, I have a yard filled with raised beds, grow bags and a perennial pollinator garden.

Vegetables, flowers and weeds comingle to produce food for my household, the birds, the squirrels and the bees. It’s chaotic and joy-creating for me while providing meaningful neighborly connections.

Slowly, over the years, my understanding of soil science has grown. Initially, I mixed bagged garden soil with homemade compost and declared it good enough. The plants grew as long as I remembered to water them and paid attention to pest and mildew problems.

Gradually, through gardening missteps and lackluster harvests, I began to learn about the complex needs of the many plants I attempt to grow. Dramatic plant failures have led me for advice to the local cooperative extension office help line more than once.

Carbon-rich soil feeds sugars and nutrients to plants and acts as a sponge, holding much-needed water for hydration. Mineral-dense soil provides potassium and phosphate. Bean and pea plants can pull nitrogen from the air (magic!), making crop rotation an essential part of successful gardening. And when the soil doesn’t have what the plants need, there is an entire cottage industry of soil amendments to help our green things grow.

But in between the compost and clay and the worms and grubs lives my favorite part of soil: the fungus. That white web uncovered in an overturned pile of mulch is garden gold, the mycelium network that acts as the fiber-optic communications channel for the plants.

Through these tiny strands, plants share resources and information with one another. The network also breaks down matter left by humans and other creatures, improving the soil’s quality and ability to support plant growth.

The importance of the mycelium’s invisible contribution to our daily well-being cannot be overstated. Working in my garden this spring to nurture the conditions for the mycelium to thrive, I have pondered how this network is a meaning-rich metaphor for pastors.

Each faith-based or church-related organization has a mission and strengths that define how it supports clergy, congregations and communities. It creates and provides a vital resource, but no single entity can offer all of the support needed for thriving communities and pastors.

We are more effective in our ministry when we understand our particular organization’s unique contributions to a thriving community — how we connect to other groups to support our people. This requires all of us to shed fears of economic scarcity and adopt a theology of abundance and collective wellness. It requires us to trust that a Creator God who has imagined a tiny fungal network into existence has imbued us with the capacities to share resources and wisdom needed to thrive together.

This eco-theological imagination complements Scripture’s many stories and metaphors that encourage us to think collaboratively about the work of being faithful in the world: the body of Christ, the sending of the 72, the formation of the diaconate in the early church. These biblical references bring meaning to local congregational and communal life, as well as the larger ecosystems surrounding pastors and faith communities. They, like the mycelium network, challenge us to share our resources and creativity with one another.

The economic realities of life in the 21st century require each of us at the personal and organizational level to ask hard questions about who we are, who we are not, and how we connect and share with others who have distinct offerings.

Our wealth is not financial; it is the relational trust we have with one another that we will not abandon one another, that we will show up to celebrate and support, to share and care. That is not to discount the need for fund development and viable economic models. Rather, the mycelium network challenges our culturally pervasive posture that economic thriving is a zero-sum game best won through resource hoarding.

The tiny, interconnecting strands of the mycelium reflect the sacred call to be in community with one another at every level of our life, work and ministry. This crucial network teaches us that we are not alone in growing thriving communities, congregations and ministers but live in a world full of living connections and relationships that make us healthier, stronger and more abundant.

The economic realities of life in the 21st century require each of us at the personal and organizational level to ask hard questions about who we are, who we are not, and how we connect and share with others who have distinct offerings.

The unmistakable scent of curry permeates the spacious commercial kitchen in Richmond, Virginia’s East End, where a half-dozen teenagers in spotless white chef coats are sharpening their culinary skills while feeding their community.

The teens scrub, peel and chop several buckets of turnips and radishes donated by a nearby farm, the rhythmic ka-THONK, ka-THONK of metal knives against plastic cutting boards broken only by whispered guidance from chef Duane Brown: Slow down, slow down. Take your time. And watch your fingers. Yep, yep, perfect.

Brown, a graduate of the Culinary Institute of America, has been meeting weekly since November with some of these teens, teaching them first the art of “mise en place” — having all needed tools and ingredients organized and close at hand — before branching out into food prep and production. On this particular evening, Brown will show them how to braise the chopped-up root vegetables in a curry sauce before pouring them over a bed of steamed rice and dividing them into 50 separate meals for low-income seniors and families in a nearby apartment complex.

At one end of a prep table, 16-year-old Malachi Sottile scrutinizes a red onion before peeling and finely dicing it. Sottile said he’s always enjoyed cooking. He was learning some tips from his grandmother before enrolling in the culinary training class, which falls under the auspices of Church Hill Activities & Tutoring, or CHAT, a nonprofit where Brown serves as the director of workforce development. Sottile’s skill set has expanded considerably over the last seven months.

“At first, it was challenging, keeping track of all the new information,” Sottile said. “But after a while, you get the hang of it.”

Alongside their knife skills, class participants pick up life skills, learning the importance of showing up on time, asking for help, working with a team, focusing on a task and communicating clearly, Brown said. At the end of the day, participants are gaining not only the ability to earn a paycheck but also the confidence to try new things, solve problems and advocate for themselves.

In addition to offering culinary training, CHAT operates three distinct businesses that also serve as training grounds for young people in an economically depressed part of Richmond: a coffee shop and cafe, a silk-screening studio, and an urban farming outfit that includes a cutting-edge hydroponic grow operation. Those businesses employ about 20 young people, most between the ages of 16 and 22; last year, 51 young people either worked for one of CHAT’s enterprises or participated in its training programs, said Hannah Teague, the director of marketing and communications for the organization.

“Ultimately,” she said, “as an organization, we want to create more and more opportunities for students and young people to help them grow personally, spiritually, socially and academically so they’re ready for whatever’s next.”

Which programs and ministries in your community help people advocate for themselves and their neighbors?

‘A rebalancing of the scales’

CHAT has what Teague calls a “scrappy origin story.” It launched in 2003 after a couple moved into the Church Hill neighborhood and turned their front porch into an informal gathering place, where neighborhood children could safely hang out and get some help with their homework. They were part of a wave of Christians, mostly white, who began moving into Church Hill from the suburbs, hoping to advance the cause of racial reconciliation and redevelopment in the state’s capital city.

That couple has since moved to South Carolina. But with guidance from the community, CHAT has expanded its scope, formalizing its after-school program, opening a fully accredited private Christian high school with priority given to low-income students from Richmond’s East End, and adding workforce training.

While there are spiritual components to CHAT’s programs, students can be of any faith — or no faith, and the organization doesn’t consider evangelism to be a primary focus. But, Teague said, “Christianity is in the ethos of everything we do.” In addition, she said, in a place that was once the capital of the Confederacy, CHAT’s programming is meant to prioritize the Black experience and center Black voices.

Brown said the seeds of CHAT’s workforce development piece were planted around 2005 or 2006 when the nonprofit launched Nehemiah’s Workshop, a woodworking operation where students handcrafted coasters, charcuterie boards, tables and rocking chairs. Jobs in the neighborhood were scarce, he said, and CHAT wanted to offer young people a “wholesome” activity where they could learn a lucrative trade.

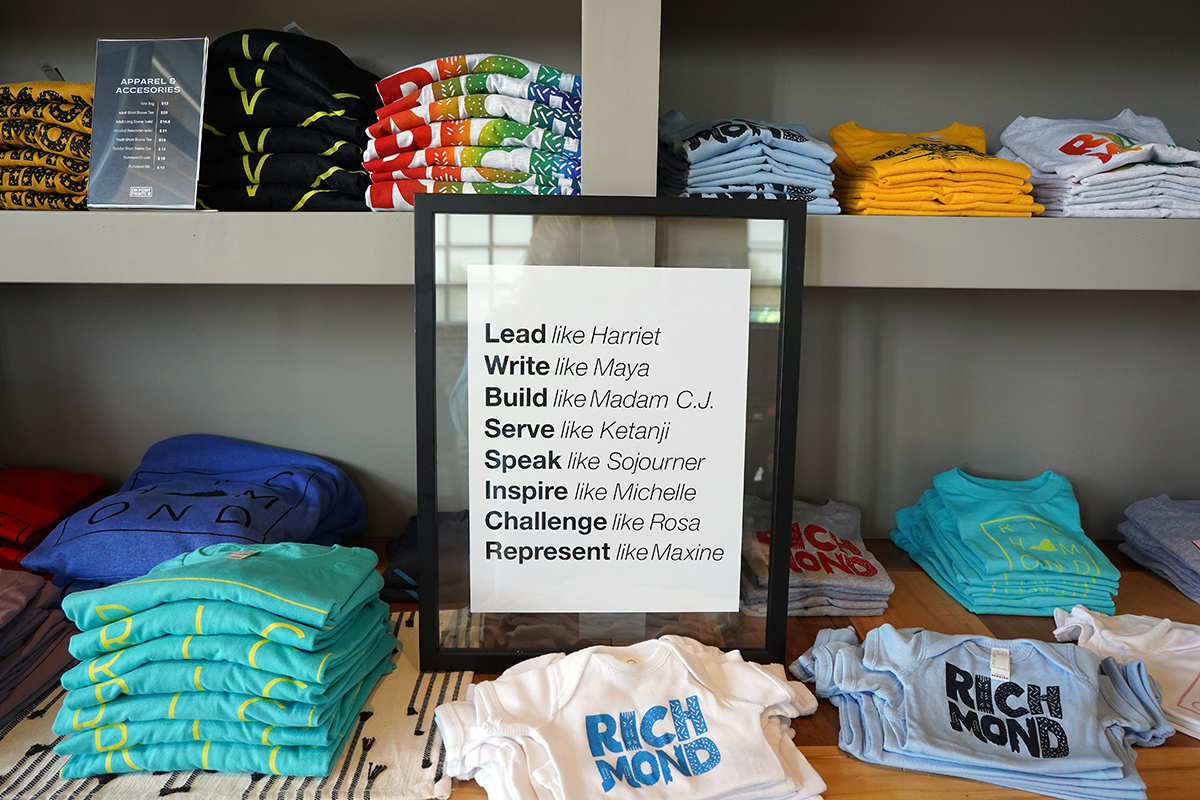

Next came lessons in sewing and silk-screening, which led to the creation of On Point Prints, a screenprinting studio that produces everything from tote bags and T-shirts to tea towels and hoodies.

In fall 2017, CHAT opened its primary food service training facility, the Front Porch Cafe, which is a breakfast and lunch spot housed in the Bon Secours Richmond Community Hospital’s Center for Healthy Living. There, about a mile north of CHAT’s main office, diners settle into comfy blue easy chairs while enjoying pastries, coffee, tea and sandwiches.

Framed photographs of neighborhood residents enjoying their front porches adorn the exposed brick walls of the interior. And some of the ingredients used in the cafe’s meals are grown at Legacy Farm, an urban gardening project, which encompasses a few parcels on CHAT’s quarter-acre property and some space in a church-owned greenhouse nearby.

Whose voices are centered in your work? Whose voices are minimized or missing entirely?

In addition, CHAT was invited last year to participate in a three-year pilot project, where students learn how to grow microgreens using hydroponic equipment. The equipment was purchased and installed by Dominion Energy, and maintenance and seeds are donated by Richmond-based Babylon Micro-Farms.

The entire nonprofit has an annual budget of about $3 million, most of which comes from private donations. Roughly 20% of that is set aside to support workforce development, said Jonathan Chan, CHAT’s executive director.

CHAT’s businesses are not motivated by profit as much as by a desire to equip young people with life and professional skills, so the enterprises are not expected to be self-sustaining. The goal, said Brown, is for the revenue from each business to cover about 80% of its expenses.

While not focused purely on money, the effort is still strategic. The organization paused Nehemiah’s Workshop to assess and research similar trainings and to gain a better understanding of the industry trends and student interest. The primary focus is on aligning with regional workforce goals and technology. Some of the workshop’s woodcraft items remain for sale online, as are items from On Point Prints. Shoppers can also pick up On Point’s tote bags, T-shirts and onesies inside the Front Porch Cafe.

All of the businesses have popped up at local farmers markets and neighborhood festivals to showcase their wares. The culinary trainees have hosted cooking demonstrations and tastings for family, friends and cafe customers. And, in anticipation of sourcing its lettuce from the hydroponic farm this summer, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts invited the Front Porch Cafe staff to host a pop-up event in late May, debuting its Summer Crunch salad, a mix of green leaf lettuce, quinoa, carrots, lentils, almonds and an apple cider vinaigrette that will be featured in the museum’s cafe.

Rebranding and exploring

Because the organization has evolved quite a bit over the last two decades, Teague said, CHAT is working on a rebranding effort that draws clear connections between all of CHAT’s initiatives: the social-emotional work of the after-school care program, the academic focus of the high school, and the vocational aspect of the workforce training initiatives. The organization is also exploring how best to leverage its connections to alumni so they can share their talents and life experiences with CHAT’s current participants.

Gentrification within the Church Hill neighborhood is also a challenge CHAT is trying to address, Chan said. Rising property values have meant that some of the families the organization has traditionally served have been pushed into neighboring communities, leading CHAT to expand its own service area beyond Church Hill proper into Richmond’s East End — even as far as neighboring Henrico County.

Right now, CHAT’s main office, along with On Point Prints and the Legacy garden, stands in the heart of Church Hill, within walking distance of several elementary schools and a Boys & Girls Club. But that may need to change down the road as families are displaced, Chan said.

The young people who participate in CHAT’s programs are full of promise, and their drive challenges false notions the general public may have about people who live in the East End of Richmond, Chan said.

How do your organization’s structure and work evolve when situations change? How do you transition out of what is no longer possible and refocus on what is?

“I think we want people to have a sense of the potential, assets and gifts of our students and that we have a rebalancing of the scales to do. We want people to interrogate their own assumptions of how the world works,” he said. “If they have negative perceptions of Black and brown students, the people who live in this area, we want those to change, to be disrupted, so they can learn how they can be part of God’s work of justice.”

‘They truly want to help you grow’

In a cramped room at the rear of CHAT’s headquarters, Timond Billie, 19, is flooding a silk-screen frame with all the colors of the rainbow to create one of On Point Prints’ popular tote bags. A senior at Church Hill Academy, CHAT’s private high school, Billie said he started working at the shop in October 2021 after hearing about it from his twin sister, Jamea, who had completed a six-week summer internship there.

How does your organization contribute through disruption to God’s work of justice?

Billie said he hopes to pursue careers in music production and real estate. The networking and marketing skills he’s picked up at On Point will help with both of those pursuits, he said. And learning about color schemes and design should come in handy when it comes to flipping houses, he said.

“I didn’t know there were so many colors — or that you could make colors out of other colors,” he said, laughing, as he pulled a squeegee through the ink, pushing the colors through the screen and onto the canvas bag beneath his tray.

Initially, Billie said, he was anxious about interacting with other people. But On Point manager Stephanie Albert was so welcoming, encouraging him to work at his own pace and to just be himself, he said, that he quickly felt comfortable. And after selling items at the neighborhood farmers markets, he doesn’t worry about chatting with strangers anymore, he said.

“I used to be really shy. But you’ve gotta break out of your shell,” Billie said. “Now, I’m confident with it.”

Like Billie, most of those who apply to CHAT’s training programs or to its job openings hear about those opportunities through word-of-mouth. Brown said he’s in regular contact with local schools, pastors and community liaisons in nearby housing complexes, letting them know when positions and new training programs open up.

In terms of tracking the progress of the program’s participants, Brown monitors whether they show up consistently and on time, how present they are when it comes to listening to instruction and completing tasks, and how well their communication skills progress, he said.

Though each workspace is a little different, Brown has accessed some youth-specific tutorials and webinars through the Federal Department of Labor’s WorkforceGPS, he said, and has gotten good advice from Catalyst Kitchens, a national network of nonprofits and regional workforce boards that operate cafes and restaurants offering job training and life skills exposure. Brown said he also makes use of industry tools, like keeping track of how many culinary trainees go on to earn their ServSafe certification through the National Restaurant Association.

The top measure of success, however, is how well CHAT instills confidence in those who participate in its workforce training initiatives, Brown said. Many of the young people who work for CHAT’s enterprises have never held a job before, he said, and many of them have little, if any, exposure to life management skills. Some face challenges with housing and transportation or are self-conscious about their struggles with math or reading comprehension. But Brown works hard to earn their trust and make CHAT a space where they feel safe enough to be honest about their needs and their goals. It’s rewarding when they share their victories with him, he said.

“There’s a point in the mentoring process where they’ve launched or moved on and you kind of stop hearing from the students,” Brown said. “And then you hear, ‘Hey, I’ve got this job interview.’ Or, ‘I got my ID.’ Or, ‘I got an apartment and a full-time job.’ And they’re demonstrating that they’ve got what they need and that they feel self-sufficient.”

Mareesha Randolph, 20, said she never really felt free to express herself or speak up about how others made her feel when she worked in retail.

“I kind of just stood in the shadows,” said Randolph, who applied for barista training at the Front Porch Cafe after a friend who was familiar with CHAT recommended it.

On her first day of work, Feb. 27, she met fellow trainee Rashá Coleman, 19, and the two have basically been finishing each other’s sentences since then. Both women said they were encouraged to ask questions and try new things, something they hadn’t experienced at their previous jobs.

What’s the word-of-mouth about your organization and its work within the community?

“With other jobs, they just throw you right in. And back in my old job, they used to stand over you,” Randolph said. “Here, if you need help, they’re here for you, but they’re not all in your face. Over here, it’s OK to make a mistake.”

She said she still gets nervous every time she hands a customer a cup of coffee, worrying about whether she nailed the order or not. But it’s gratifying when the person takes a sip and smiles or gives her a nod of appreciation, she said.

“You shouldn’t let fear stop you from doing things you could be great at,” Randolph said. “It’s OK to try new things. That’s how you figure out what you like and what you don’t like.”

Randolph said she’s been surprised by how much she’s learned, everything from how to steam milk “so it’s not screaming at you” to how to create latte art — she’s recently mastered making a heart pattern.

She hopes to use the practical skills to get a job at a coffee shop in New York when she moves there in the fall for acting school. But the other experience she’s gained — speaking with members of the public at pop-up events, working during the high-pressure lunch rush, learning how to read customers’ body language and respond with empathy — will be invaluable in any work environment, she said.

“They’re just so friendly, and you can feel that they truly want to help you grow. They gently push you into the areas you need,” Randolph said. “And the way they do it, you didn’t realize you really needed those skills until you have them.”

Questions to consider

- Which programs and ministries in your community help people advocate for themselves and their neighbors?

- Whose voices are centered in your work? Whose voices are minimized or missing entirely?

- How do your organization’s structure and work evolve when situations change? How do you transition out of what is no longer possible and refocus on what is?

- How does your organization contribute through disruption to God’s work of justice?

- What’s the word-of-mouth about your organization and its work within the community?