Dignity and respect are the key to a multimillion-dollar ministry supported by a successful thrift shop

During the COVID-19 closures of 2020 and 2021, the leaders of Dorcas Ministries decided to remodel their popular thrift shop to look and feel like a T.J. Maxx, the off-price retailer with discounted items from name-brand fashion to home decor.

The shop, located in a former grocery store in Cary, North Carolina, was already a treasure trove for bargain buyers. The new look made it even more enticing.

The Dorcas Thrift Shop space is mostly taken up with lightly used clothing, rack upon rack, neatly organized by type. At one end of the cavernous building are multiple shoe shelves arranged by size. Handbags, belts and scarves line a wall.

Closer to the checkout points are seasonal items — right now, Halloween costumes — and farther down, toward the rear of the store, shelves stocked high with housewares. In between, glass cases sparkle with vintage jewelry.

Customers flock to the shop from all over Wake County and the surrounding region. After browsing with shopping carts or tote bins, they pay in cash or with credit or debit cards.

The average cost of an item? $2.50.

There’s a reason the thrift shop, which anchors a plaza owned entirely by Dorcas, tries to model its services on professional business practices.

The ministry sees that as a way of treating people of all income levels fairly and eliminating barriers to social mobility.

“Our job is to treat everyone like God’s children, with the compassion, dignity and respect they deserve,” said André Anthony, the ministry’s CEO. “That’s our primary focus.”

Volunteers help neighbors thrive

That formula appeals not only to low-income shoppers but also to a healthy corps of middle-class volunteers from Cary and Morrisville, affluent suburbs of North Carolina’s capital of Raleigh, who have helped make the ministry a success.

The ministry takes pride in having earned Top 10 ratings in the “Best Thrift Shops” category on Yelp, the crowd-sourced review platform. On a typical weekday morning, several dozen people wait outside the shop ready to make their way in as soon as the doors open at 11 a.m.

Started 55 years ago by a group of women from nearby churches, the ministry takes its name from the seamstress Dorcas, mentioned in the book of Acts as “always doing good and helping the poor” (Acts 9:36 NIV).

Last year, the shop generated $3.2 million in sales. It used that income to provide $2.2 million in financial assistance to the area’s poor, becoming a premier social welfare agency for a region of more than 200,000 people.

Dorcas employs 27 full-time staff, but it relies on 600 dedicated volunteers, without whom it could not fulfill its mission of “helping neighbors thrive.” Its volunteers, many retired from careers as IT specialists, corporate executives and health care professionals, are eager to give back to their community.

What compelling vision does your organization use to inspire volunteers?

Some 500 of those volunteers take one or two weekly three-hour shifts sorting, cleaning, fixing, pricing and labeling the avalanche of donations that accumulates daily at the shop’s rear dock.

Impressive as it is, the thrift shop is just the foundation of a vast set of services that Dorcas offers with income from the store. That’s where about 100 additional volunteers with experience working with people in difficult life circumstances apply their talents.

In 2022, Dorcas helped 2,000 families (or about 5,800 individuals) with emergency financial aid and other services at its crisis center located in offices next to the thrift shop. Those helped are typically low-wage workers living paycheck to paycheck who, because of divorce, illness, the birth of a child and/or lack of paid parental leave, fall behind on their rent or are facing eviction.

“Dorcas is probably the most significant social ministry in our area in terms of how many people they serve and the kind of services they provide,” said the Rev. Wolfgang Herz-Lane, the senior pastor of Christ the King Lutheran Church in Cary, one of 40 area congregations that regularly donate financially to the ministry.

Christ the King provides Dorcas with a steady stream of volunteers and refers people in need. So much so, Herz-Lane said, that he thinks of it as a “social ministry arm of our congregation.”

Helping people in crisis

Like the thrift shop, the Dorcas crisis center is modeled on an ethic of respect and dignity for all. A receptionist greets people and directs them to private rooms where they meet with case workers to assess their needs and come up with plans to address their financial difficulties.

How do you communicate your vision and invite potential volunteers to be part of it?

Clients at the crisis center receive checks — usually within 48 hours — to help pay for rent or utilities. Dorcas may even help pay for veterinary care (addressing the No. 1 reason pets wind up in shelters — families’ inability to pay veterinary bills).

But the aid doesn’t stop there. Clients receive ongoing counseling and other services for a period of three months to a year. That may include one-on-one career coaching, cash stipends for those willing to enroll in workforce training classes at the local community college, or preschool scholarships for children.

“We don’t just hand them a check for rent assistance; we hand them a check and say, ‘OK, let’s talk through some changes that can be made,’” said Sally Goettel, a former Dorcas board member who continues to volunteer there. “By getting that holistic approach, it’s just so much more effective.”

At the crisis center, clients can also take advantage of a mobile University of North Carolina nursing clinic that provides free basic preventive care, including school physicals, every Tuesday morning and twice a month on Saturdays.

But the most basic form of support the ministry provides is food.

Food assistance for families in need

Similar to the T.J. Maxx-inspired thrift shop, the Dorcas food pantry, located a few doors away, is modeled on a high-end food store. Dorcas clients can take a cart and browse a wide selection of prepared foods as well as fresh fruits and vegetables, dairy items, baked goods, paper goods, diapers and even cat food. Grocery shelves are labeled in English and Spanish. Recently, the pantry started a Taco Tuesday meal kit. (About 8% of Cary residents are Hispanic.)

Here, too, the idea is to treat people with respect — not just to give them a handout. While anyone can shop at the Dorcas thrift shop, the pantry is reserved for families in need who have gone through its client services intake.

“It’s not a preselected bag of food,” Anthony said. “It’s very much client choice. It’s intentionally set up where, when you walk in, you feel just like anybody going to a grocery store.”

If you have an idea for Christian social entrepreneurship, could it be supported with an active volunteer base?

Sallie Whelan, a retired schoolteacher, said it’s the interaction with clients that makes the food pantry such a satisfying volunteer experience.

“I wanted to do something in my retirement that would go towards my philosophy of helping people,” said Whelan, 67. “We’re working directly with the people that are shopping — helping them find something that they’re looking for or explaining the process to them.”

Founded on faith and dignity

While the ministry is motivated by the Christian faith of its founders, the employees and volunteers do not ask clients about their faith and only mention its Christian roots if asked. Among the 40 congregations supporting Dorcas, one is a synagogue; another, a Hindu temple.

“Whether they’re Christian or whether they’re Hindu or whether they’re purple or whether they’re green, if you want assistance and you live within the geographic region that Dorcas supports, they can assist you along a path,” said Barbara Bostian, 66, who volunteers as a career coach and serves as vice chair of the ministry’s board of directors.

That desire to help neighbors is how Dorcas got its start. In 1968, a group of mostly white women from Cary’s downtown churches that had been meeting for a Bible study decided to add a service project.

Southern schools were still segregated in those days, and the women decided to form a class for Black children who didn’t have access to kindergarten.

They drove through town, stopping at homes where they spotted a clothesline with children’s clothes or toys on the front lawn. About 40 children eventually enrolled and met at a local predominantly Black church.

Thus was born Christian Community in Action, still Dorcas’ legal name.

How does your faith community offer support while maintaining the respect and dignity of its neighbors and clients?

Soon after the program began, people started donating clothes for the children, and a small clothing closet was set up. To help preserve people’s dignity, CCA began charging people a nickel or a dime for each item. This was the start of the Dorcas Thrift Shop.

“They started putting money in a jar,” said Jill Straight, Dorcas’ senior director of client services and advocacy. “And then when one of the families they were working with needed help with a light bill or water bill, they used the jar of money to help with the bill.”

By 1972, the thrift shop transitioned from a church closet to a downtown apartment. The kindergarten program ended in 1980, but the thrift shop continued to grow.

After moving half a dozen times, the ministry bought an old strip mall in 2008 and invested more than $4.5 million in building upgrades. It rented out adjacent spaces to other nonprofits, including a Habitat for Humanity ReStore, an after-school literacy program and a behavioral health care management group.

Dorcas Plaza also includes a few for-profit businesses — one of which, a pool hall, has been a good neighbor to the ministry, contributing money through fundraising drives.

These sound business decisions have helped the ministry boost its volunteer roster. Each week, a Dorcas staff member conducts an orientation tour for potential volunteers. On a recent Tuesday, those included a handful of retirees and a young man with developmental disabilities.

Shelley Hobbs, Dorcas’ director of marketing, gave the group a behind-the-scenes tour of the thrift shop, the food pantry and the crisis center.

All were familiar with the Dorcas Thrift Shop, and several said they had shopped there for years. One of them, Carolyn Jungclas, had recently retired from a career as head of procurement for First Citizens Bank.

Jungclas, 60, described herself as a crafter who loves to sew. She wanted to volunteer to sort through the linens and fabrics the thrift shop receives. A friend had told her that Dorcas could use her help.

“I’m a firm believer, from the Gospel of Luke, that to whom much is given, much is expected,” Jungclas said.

But what impressed her most was the ministry’s emphasis on treating people with dignity.

“To me, that just is so key,” Jungclas said. “I’m hoping to start as soon as possible.”

How do your volunteers describe the work of your organization? How do they describe working for your organization?

Questions to consider

- What compelling vision does your organization use to inspire volunteers?

- How do you communicate that vision and invite potential volunteers to be part of it?

- If you have an idea for Christian social entrepreneurship, could it be supported with an active volunteer base?

- How does your faith community offer support while maintaining the respect and dignity of its neighbors and clients?

- How do your volunteers describe the work of your organization? How do they describe working for your organization?

A world made out of love: Creation

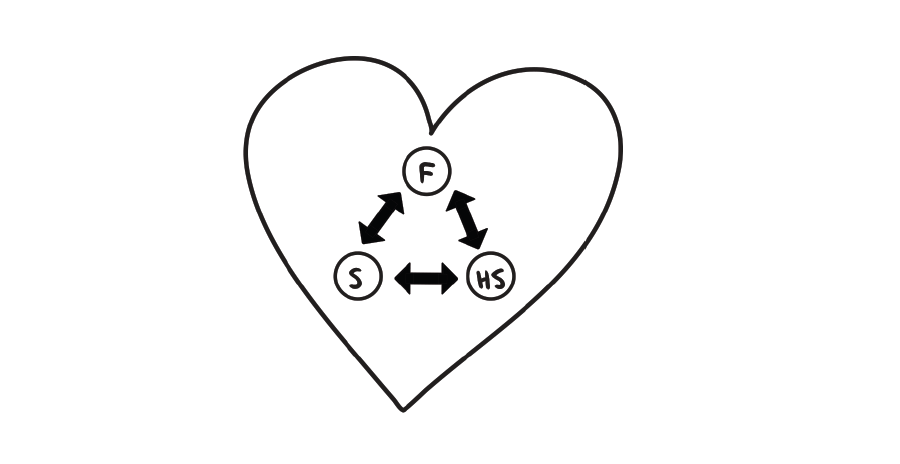

When we talk about the Trinity, we talk about love: the three persons of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit in an ever-moving, ever-giving dance of love.

When we talk about creation, we also talk about love: the love amongst the three persons that spilled out into sun and sea and you and me.

Theology has a couple different terms to talk about these loves and how the Trinity works in relation to itself and in relation to what has been created.

When we think about that dance of love that Father, Son, and Spirit spin and move in, the inner life of these three persons, we are thinking about the immanent Trinity. When we say “immanent,” we mean “internal,” “innate,” “inside.” This is a pretty mysterious concept, because there’s only so much we can know and say about what goes on inside the Godhead apart from what we can see in the world around us.

But we can say a few important things. The apostle John put it neatly in his first letter to some early Christians: “Whoever does not love does not know God, for God is love” (1 John 4:8). God does not simply have love, or give love. Love is not simply an attribute of God; it’s God’s whole being.

And God chose to allow that love to burst out of God’s very own self.

‘When God began to create the heavens and the earth …’

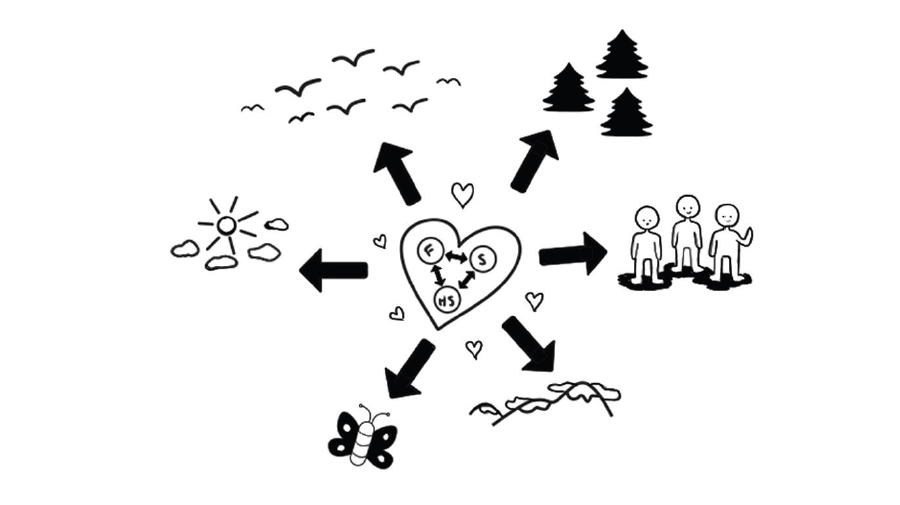

This is where we begin to see the economic Trinity at play — the Trinity in its relation to what is not God, in relation to what God has created. God could have chosen to just remain as the immanent Trinity forever, having nothing to do with that which is not God. The love flowing freely between the persons of the Trinity would have been enough for God. Father, Son, and Spirit were not sitting around sulky, moping, in need of praise and adoration.

Creation wasn’t necessary.

Our world did not need to exist. Everything we see and smell and taste is excessive: an outpouring of God’s love. God didn’t need to create humans or frogs or planets to satisfy some whim or to appease some lack. God didn’t need us.

But God wanted us.

There’s a phrase attributed to St. Augustine: Amo; volo ut sis. Translated from Latin, it reads: “I love you; I want you to be.” Imagine, for a moment, God whispering this as the heavens and the earth began to take their shape, as Adam was formed from the dust and breathed into life. “I love you; I want you to be.”

God needs nothing — but God wants us to be. And in creation, God wanted to share the love that is God’s own self and being. In creating, the love within the Trinity flooded over into every nook and cranny of the cosmos, every inch drenched in it.

‘… the earth was complete chaos, and darkness covered the face of the deep …’

So God didn’t need to create, but God chose to, freely. That’s a statement we need to make when we talk about creation. There’s another piece to it, though: that God created out of nothing.

When we humans “create,” we use paints, bricks, computers, thoughts in our minds: things that already exist. When God created (in the truest sense of that word), God used … nothing.

The term theologians use to describe this concept is (you guessed it) a Latin phrase, creatio ex nihilo, which translates to “creation out of nothing.” This sets God apart from any one of us, and it sets God far beyond the reaches of any technology or tool we might develop. Only God can take nothing — a void of voids — and create.

The scholar Janet Soskice puts it like this: “Creatio ex nihilo affirms that God, from no compulsion or necessity, created the world out of nothing — really nothing — no preexistent matter, space, or time.” This concept of “really nothing” is essentially impossible for us to fathom. How can we imagine this kind of emptiness? What creatio ex nihilo does is force us to confess just how transcendent, just how “other,” God is.

But it also shows us another key thing about God.

Many centuries ago, in an English town called Norwich, a woman lived inside a church.

The woman, who became known as Julian of Norwich, lived the life of an “anchoress,” voluntarily secluding herself in a cell within the church walls so she could devote herself to prayer and worship.

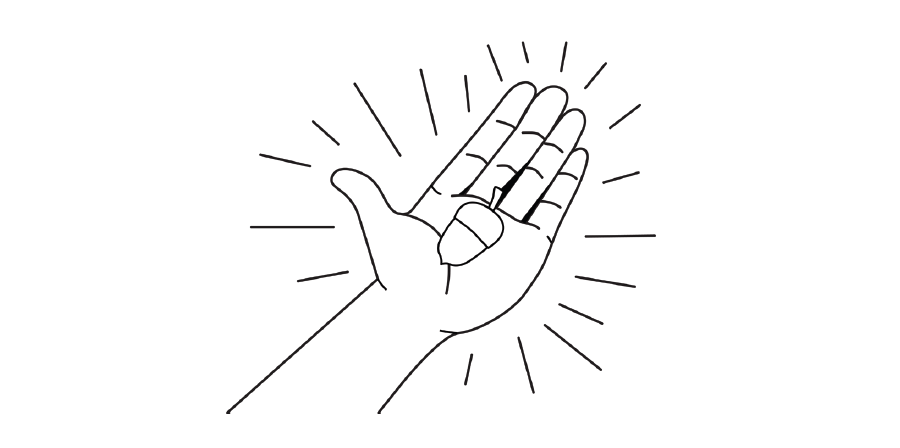

She spent many years there, sifting through and making sense of some remarkable things that had happened to her. She wrote a book, “Revelations of Divine Love”— the first book written by a woman in the English language — about a series of “showings” she had received from God during a severe illness. These showings were often dramatic and graphic, showing the suffering Christ in vivid detail, but one of them included a simple image.

And in this vision he also showed a little thing, the size of a hazelnut, lying in the palm of my hand, and it was as round as a ball, as it seemed to me. I looked at it and thought, “What can this be?” And the answer came to me in a general way, like this, “It is all that is made.” I wondered how it could last, for it seemed to me so small that it might have disintegrated suddenly into nothingness. And I was answered in my understanding, “It lasts, and always will, because God loves it; and in the same way everything has its being through the love of God.”

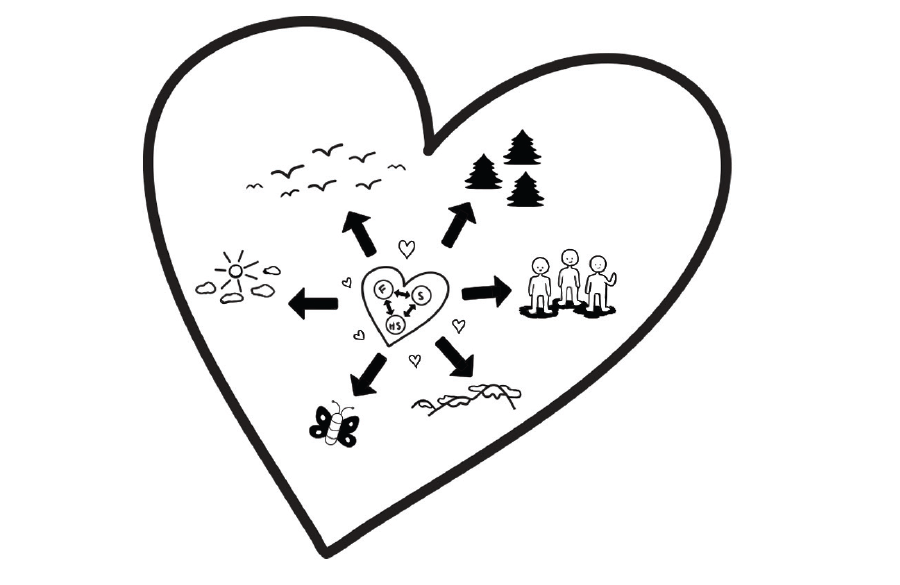

God is transcendent and “other,” yes. But God also knows us and sustains us in a profound and personal way. This is not a watchmaker God that some philosophers have spoken of: a God who puts together a watch and then steps back to let it tick away. God is not aloof. We last because God loves us. We couldn’t exist without that love — the enveloping love of a God who is both utterly beyond us and beside us.

To emphasize that God sustains us and all of creation, theologians often reference the idea of creatio continua, another fancy Latin phrase that means that God constantly upholds all of creation.

God did not simply, at one time, desire to create the world. God always wants the world; he consistently calls what he made “good.” God actively re-creates the world in every single moment. God always wants us, and everything, to be.

What happens when we start to forget some of these ideas about creation?

Much of Christian theology ends up being centered around the person and work of Jesus Christ — which makes sense, considering the name “Christian.” The attention we give him is well-deserved, after all. But sometimes the way that focus plays out results in some long-term damage — like when the doctrine of creation starts getting squashed.

A weak theology of creation is bad news for creation. If we focus so much of our energy on ourselves as humans, on what God has done for us, and we don’t pay much attention to the rest of the universe that God made, we end up staring at a tiny piece of the big picture that is God’s love and care for the world.

A Native American theologian named George Tinker knows this all too well. He writes about the ways Christian missionaries preached the gospel to Native Americans, giving it the usual Western-church spin of humanity’s fall from grace, their sinful nature, and their need for redemption. For traditionally oppressed and marginalized peoples, however, the emphasis on humanity’s sin and their need for a savior doesn’t sound like the best news. “Unfortunately,” Tinker writes, “by the time the preacher gets to the ‘good news’ of the gospel, people are so bogged down … in [their] internalization of brokenness and lack of self-worth that too often they never quite hear the proclamation of ‘good news’ in any actualized, existential sense.”

Tinker calls for us to start sharing the good news from, well, the beginning of it all: that first “in the beginning.” He asks for us to “take creation seriously as the starting point for theology rather than treat it merely as an add-on to concerns for justice and peace.”

When we begin to neglect the significance of creation — what it says about God and God’s love — we can find ourselves getting so wrapped up in our own lost-ness and need that we forget just how loved we have always been, just how valuable everything and everyone around us is. When our theology becomes centered on “just Jesus and me,” our sisters and brothers — our whole planet — suffers.

What might it look like to take creation seriously, then — to remember how God holds us tight and close, wanting us to be?

What might it look like to remember that we live in a world that God wants?

God’s creation is vast and expansive. God does not choose to be God only for God’s own self — God is the One who delights in extending love and life to others. God’s good world — created and sustained by God’s loving-kindness — is worth knowing and celebrating and protecting.

Luckily for us, God chooses to reveal to us more of what we, creation, and God are like. That’s what we’ll look at in the next chapter.

From “Napkin Theology,” by Emily Lund and Tyler Hansen. Copyright © 2023 by Emily Lund and Tyler Hansen. Excerpted by permission of Wipf and Stock Publishers. All rights reserved.

Not too long after I joined the pastoral staff of a church, another team member gave me some feedback from our senior pastor’s wife.

“The pastor’s wife is uncomfortable with you sitting in the chair next to her husband,” the staff member told me — she feared that congregants would think I was his wife.

I sat in the pulpit’s second row for the next five years. Hyperaware of my presence as a single woman on the pastoral staff, I never spoke about this conversation again.

I often felt alone and misunderstood, and I wondered, do other Black clergywomen experience such challenges? I resolved to find out, and applied for a Reflective Leadership Grant to conduct an ethnographic study of Black clergywomen.

I wanted to explore the challenges, but I also wanted to talk to women who were flourishing and cultivating space for other women in ministerial leadership. I focused on the question, What makes Black clergywomen thrive?

I interviewed 11 Black clergywomen and 25 congregants, along with scholars whose work includes areas of Black women and religious studies. There were seven denominations represented.

During my research, I came to realize that I was not alone in my challenges.

The Rev. Dr. Renita J. Weems aptly articulated the shared experiences of a majority of interviewees when she told me, “Black women, especially single ones, make the best work mules — grossly underpaid and obscenely overworked. We forget our boundaries because Christianity and ministry have elevated sacrifice and silence in women as a virtue. Women have to learn the importance of boundaries, saying no and saving parts of themselves for themselves.”

Yet that’s not the whole story. In spite of the opposition that Black women have faced for centuries, I saw that they are dismantling that which is destructive, oppressive and seeks to limit their thriving.

I heard many hopeful stories. Women are refusing to give most of their time and energy to demanding respect or legitimizing their work, instead devoting themselves to preaching in pulpits, writing books, transforming communities through social activism, traveling abroad and living dreams that would have seemed impossible to their ancestors.

I am sharing some of the findings of my project, from which I identified three key factors that contribute to the flourishing of Black clergywomen.

Intentional self-care

Black clergywomen who flourished were not only committed to providing care for communities; they prioritized it for themselves. They were committed to rituals, rest, friendships and activities that nourished their souls.

“We [Black female pastors] try to bear [the] whole world and lose ourselves. … Joy has to be our active form of resistance,” said the Rev. Cece Jones-Davis, who serves on the pastoral staff at The Table in Oklahoma City.

She said that part of her routine was watching a comedy show before going to sleep, “even stuff that’s not good, because I need the lightheartedness before I can rest.”

Clergywomen said they exercised, received regular massages, cooked meals and went on vacations.

Others learned to ask for what they needed to thrive, including sabbaticals, therapy sessions and, in some cases, travel funds for a spouse or a child to accompany them to ministry engagements.

Congregational ethos of care

Black clergywomen flourished in congregations that had an ethos of caring for them. In these spaces, they were paid well, and their contributions were valued and respected.

Elders and other congregational leaders understood the importance of supporting their well-being, including paying for professional and personal development.

Yet even where Black clergywomen were flourishing, they were often carrying more than their share — and suffering for it. Some churches claim to be progressive and egalitarian, but when you examine the roles, responsibilities and organizational charts, those ideals are not borne out in practice.

For those who hire and work alongside Black clergywomen, consider it your responsibility to assist in dismantling practices that silence, harm and prevent them from being able to speak up and show up as their full selves.

Congregational openness to new approaches

I also found that Black clergywomen thrived in places where congregations and their leaders showed an openness to dismantling systems and practices that hindered their expression of their whole selves.

In some churches, leaders were willing to re-envision and restructure hegemonic leadership and worship practices destructive to Black clergywomen — and the wider community.

Congregants at St. Paul’s Baptist Church in Philadelphia told me about changes that happened when the Rev. Dr. Leslie D. Callahan became the senior pastor in 2009. Among them: learning to use inclusive language.

“The God-talk is different here. It is not what we were raised with or accustomed to,” an associate minister at St. Paul’s told me.

I found that Black clergywomen who were flourishing had been encouraged and permitted by denominational and congregational leadership to re-imagine new ways of leading and loving themselves and their congregations.

Their churches tended to show more signs of collaborative leadership; people in the decision-making circles did not all look alike, think alike or share the same educational and socioeconomic backgrounds.

Through making changes in liturgical practices, church governance and teachings that expand the imaginations of their congregants, Black clergywomen are modeling what it means to invite others into their liberation.

Their very work shows promise in that the life-giving traditions that have sustained Black people for centuries can be amended and overhauled to give more possibilities for the flourishing of wider communities.

What will it take for churches to consider other models, beyond the personality of one (usually male) person in the pulpit and the work of women behind the scenes?

It was not until I had the space and time to listen to the stories of Black clergywomen that I allowed myself to wrestle with the problematic situation I encountered in my previous church setting.

Why did I feel I had to stay silent? Why did we as a staff not teach people that a woman who holds power and is next in line to the pastor does not have to be his wife? Why did I move to the second row instead of working with my congregation to dismantle the prevailing assumptions about a woman’s role in the church?

I was heartened to talk with Black clergywomen who are doing just that — taking care of themselves while changing the church. My hope is that they will not be left to do this work alone.

In 2017, I was the pastor of a small-membership church, and my wife was a youth pastor at a church in the next city over. A week before Christmas, our 6-month-old daughter woke up with a high fever and a nasty cough. Her breathing was so labored that we took her to the emergency room.

She was admitted and put on oxygen. The doctors assured us that she would be fine — she had a bad case of RSV, which just needed to run its course. But for the next three days, she lay in her crib, an oxygen tube in her tiny nostrils, an IV in her tiny arm.

For a parent, there are few things more gut-wrenching than sitting helplessly beside the crib of your sick child.

For a young pastor married to another young pastor, there is no worse timing for such a crisis than mid-December. Between the two of us, we had a combined five Christmas services that needed to be planned and executed.

But it was this experience that really drove home to me the power of relationships in a small-membership church.

One day, while my daughter was napping, I called one of my lay leaders to talk through the rapidly approaching services.

My parishioner picked up the phone with a curt but well-meaning greeting: “Why are you calling me? Don’t you have other things to worry about right now?”

She knew me, and with those first comments, she let me know that she cared about me.

Rural and small-membership churches are places that depend on deep relationships. Carl Dudley has argued that small-membership churches are often single-celled organisms, with that single cell functioning as a caring unit.

Within a small church, the members tend to each other. If someone is sick, meals are arranged almost spontaneously. If a parishioner needs something from the church but can’t ask, other members will reliably let the pastor know. If someone has a small business, members are sure to shop there.

Members of the small church depend on one another — for connection, for friendship, for help.

Like most strengths, this can have a negative side. At times, small-membership churches have been criticized for focusing too much on internal relationships — an inward focus that can inadvertently close the community off from the outside world. It can be difficult for new members to gain entrance to that caring cell.

Yet with the world locked into physical distancing and isolation, I’ve been thinking a lot about the positive side of those relationships, that sense of community. In times of sickness and anxiety, it can be a powerfully sustaining force. It is one of the principal gifts of a small church.

I was the beneficiary of that calming gift that day on the phone. I explained that there was a lot of stuff to get done: people who needed to be called and visited, services that needed to be planned.

“We can handle those things,” my parishioner said. “Your daughter is in the hospital. You can call me when you’re home again.”

I was overwhelmed, both by the way my church cared for me and my family and by the leadership demonstrated by this depth of care.

Much of my work now is helping leaders of small-membership churches grow their confidence in organizational and institutional leadership, so that they can claim their role as anchor institutions within the community.

But what happens when church committees don’t meet in person and Sunday worship happens virtually or over a conference call?

I think this is when the strengths of the small-membership church are most apparent.

The early church persisted in part because it was networks of small groups that met when they could. This allowed the church to spread beneath the radar of those who wanted to stamp it out.

Our small churches today continue to exist for the same reason — deep relationships that draw people in and form them in community.

During the pandemic, I’ve been captivated by the stories of leadership I’m seeing in small churches. Pastors who print weekly devotionals and Bible studies and deliver them to parishioners — a friendly but physically distant presence waving at members through the window, reminding them they are not alone.

Lay leaders who organize phone trees to make sure everyone is checked on and connected with a friendly voice. Leaders who host conference calls where people can share their prayer requests and have others respond.

On Palm Sunday, we received a text message from the volunteer children’s director at the church where we attend and volunteer as youth pastors. “You’ve been egged,” it said.

Out in the yard were 24 brightly colored plastic eggs. A gift bag with a palm leaf and a book about ducks — my daughter’s favorite animal — was on the porch.

In place of the community Easter egg hunt, volunteers were scattering eggs in the yards of the kids and surprising each with a personalized goody bag.

As my daughter ran around the yard, I found myself grateful for the community that knew us and remembered us, a community that reminded us we were still cared for and were not alone.

In this time of uncertainty, we might turn to the small-membership church for guidance and wisdom. We can learn from the ways that leadership in a small church is not bound by established institutional channels — the ways that committed silos break down over family dinner conversations, that pastoral care is shared among all the members.

My daughter’s RSV was not COVID-19, but when I lingered in the uncertainty of her illness, I depended upon the relationships, the compassion and empathy, that were foundational to my church.

In a world where “social distancing” is now common language, the small church can help us recover this formational life of community, forged through deep relationships that sustain us even in uncertain times.