Churches need to do the work of welcoming others and their stories

Languages carry stories. Oral Indigenous societies pass family and cultural stories down generation to generation to preserve culture. To be able to hear one of our Potawatomi stories in Potawatomi is an absolute honor, because it connects me back to who we once were and who we still are today. Even though colonization has taken so much from us, telling our creation narrative or our winter stories, even in English, still means something. Telling our experiences, like I’m expressing my experiences to you in this book, is a sacred kind of work, and as we pass our stories and experiences down to our children, we are changing our children, changing ourselves, and changing the world.

In 2017 I hosted an event in our city focused on the conversation surrounding Indigenous people and the events that unfolded in Standing Rock, North Dakota. The Dakota Access Pipeline was originally set to go through Bismarck, North Dakota, a predominantly white city, but it was rerouted to go through an area near the Standing Rock Sioux reservation, so that it impacted Indigenous peoples and their water supply. In response, Indigenous peoples and their allies gathered from all over the world to fight against a pipeline that would poison the water in Lake Oahe and the Missouri River. The event was created to give voice to Indigenous peoples and allies who went to Standing Rock to show support to water protectors, and as someone who did not go to Standing Rock, I wanted to listen, engage, and learn for myself. As the event drew closer, many of the people who were going to share were unable to come, so there were only a few of us left. I decided to open up the microphone to anyone attending and make it a public storytelling event. My friend Jonathan from the Navajo Nation stepped up to the microphone. He reminded us that we belong to each other, that we must stick together and have honest conversations for the sake of a better future. I deeply felt every word, remembering how much language and expression matter, how important it is that we speak to each other in peace and with honesty, especially when we are so divided around so many things. Can you imagine if all over the country we hosted storytelling events, inviting people to step up to a microphone? Yes, it could go wrong, but it could also go so right when people are given space to lead with vulnerability and humility. People could tell their stories of surviving trauma, their stories of beating cancer or still fighting against it. Others might tell about what it’s like to be a queer woman of color in America or a Sikh man in America who battles hate crimes against his community daily. Still others might talk about what it’s like to be lonely or in love or both. You see, our human expressions, no matter how varied, still bring us together in ways that we cannot always understand, and language is the force that guides us.

In 2017 I hosted an event in our city focused on the conversation surrounding Indigenous people and the events that unfolded in Standing Rock, North Dakota. The Dakota Access Pipeline was originally set to go through Bismarck, North Dakota, a predominantly white city, but it was rerouted to go through an area near the Standing Rock Sioux reservation, so that it impacted Indigenous peoples and their water supply. In response, Indigenous peoples and their allies gathered from all over the world to fight against a pipeline that would poison the water in Lake Oahe and the Missouri River. The event was created to give voice to Indigenous peoples and allies who went to Standing Rock to show support to water protectors, and as someone who did not go to Standing Rock, I wanted to listen, engage, and learn for myself. As the event drew closer, many of the people who were going to share were unable to come, so there were only a few of us left. I decided to open up the microphone to anyone attending and make it a public storytelling event. My friend Jonathan from the Navajo Nation stepped up to the microphone. He reminded us that we belong to each other, that we must stick together and have honest conversations for the sake of a better future. I deeply felt every word, remembering how much language and expression matter, how important it is that we speak to each other in peace and with honesty, especially when we are so divided around so many things. Can you imagine if all over the country we hosted storytelling events, inviting people to step up to a microphone? Yes, it could go wrong, but it could also go so right when people are given space to lead with vulnerability and humility. People could tell their stories of surviving trauma, their stories of beating cancer or still fighting against it. Others might tell about what it’s like to be a queer woman of color in America or a Sikh man in America who battles hate crimes against his community daily. Still others might talk about what it’s like to be lonely or in love or both. You see, our human expressions, no matter how varied, still bring us together in ways that we cannot always understand, and language is the force that guides us.

One of the church’s biggest blind spots is ignoring the stories of those on the outside. We hide behind dogma and theology instead of leaning into our humanity to connect with one another or to the land. But when we stop to look out a window and see what is happening outside, or when we step outside the door of our home to breathe the fresh, cold air, we are taking in the stories of the earth. As Anishinaabe author Richard Wagamese writes, “When you break the connection that binds you to money, time, obligations, expectations and concerns, the land enters you. It transports you.” And when we step back into those spaces again, those spaces filled with noise, we have stories to tell. I find that when I go outside to listen to the language that only the land speaks, she sends me back with poetry. She sends me back with a connectedness to both her soul and mine that can be expressed only in words that have rhythm and movement and life to them.

When the wind blows, we imagine she is erasing every injustice,

sweeping misdoings from the east to the west,

making room for something new, a more whole world.

Instead, what we don’t realize is that she is rustling the tree branches

to sing us a song.

Instead, she is sowing seeds across the landscapes,

seeds that tomorrow will become the beauty that restores us.

Instead, she is whispering for us to hold on, to keep going,

to water those seeds, because one day, they will show us the way home.

Poetry is life to us and to those around us. Throughout time, our poets are often our prophets, the ones who dance and sing and write, expressing things we did not know were stirring inside us for years. Our poets, our storytellers, are the bridge between the languages of the earth and our spoken languages, between the stories of the earth and our stories. May we all learn what it means to be poets who step outside and back inside, made new, sacred language flowing from our lips to and for one another.

We live in an era in which we are beginning to dig deeper into questions of how we got here. We are asking why there is so much injustice, why so many of our police are corrupt, why Black men can’t kneel during the national anthem, and why a holiday called Columbus Day is offensive. Language creates cultures, cultures create nations, and leaders of nations tend to write history, and we must ask what our language evokes, whether we are using it for good or for evil.

We live in a time when Black people, Indigenous people, and other people of color are speaking up, sharing our stories, redefining what it means to be alive in America — but let’s acknowledge that many of these people have been speaking up for a long time and are only now being heard, if heard at all.

Thanksgiving 2018 was a really difficult time for me. Native American Heritage Month happens in November, so while we are celebrating that we are still here, we are bombarded with Thanksgiving myths and people asking us for all the resources they should have been asking about any other month of the year. Kind, well-intentioned parents message me asking for book lists to read to their children, churches email me asking for Thanksgiving reflections that don’t center celebration of Pilgrims or sometimes even inviting me to preach, unpaid, on a topic that is really difficult for me, and I struggle to find the right language to express my exhaustion.

In 2018, when my inboxes were full of these messages, I finally went to my social media accounts and made an announcement asking people to stop messaging me, to do the work themselves, and to stop expecting Indigenous peoples to give more than we already give every day of the year, especially at Thanksgiving. It is a time of confusion and mourning, and I honestly don’t have anything left to give others in that space. Non-Native people responded, held me up, thanked me for speaking, and some of my white friends apologized. One friend sent me a gift a few months later, with a note of both thanks and apology, a bag of coffee mailed with it. I drank that coffee and thought of my friend every day, thought of the kind of ally she wants to become. We all make mistakes in these conversations, and we have to be willing to step beyond our fear of saying the wrong thing to ask hard questions and have honest conversations about where we go from here. My non-Native friends have to understand that the myths told at Thanksgiving only continue the toxic stereotypes and hateful language that has always been spewed at us, and they have to do the work to educate themselves about a better way. Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz and Dina Gilio-Whitaker wrote a book on this topic called “All the Real Indians Died Off”: And 20 Other Myths about Native Americans. In the introduction, they write, “For five centuries Indians have been disappearing in the collective imagination. They are disappearing in plain sight.”

Indigenous peoples cannot fight against these mistruths alone. Conversations about replacing Columbus Day with Indigenous Peoples Day shouldn’t be happening just once every year or just within circles of Native people. It should be discussed in city planning meetings, and our street signs should be renamed if they carry traumatic names or celebrate the people who committed atrocities throughout history, because language is about the fabric of a place, what we create, how we explain who we are, who God is, and what the responsibility of those in power must be. To be a place of “we the people,” we have to be a place that is truly for all people, and how do we do this if we don’t talk about the stolen land that America rests on? How do we do this if we don’t talk about Confederate monuments and schools named after racists? The answer is with all of us; to tell the truth is to give language to experiences that are often ignored by society.

From the book “Native: Identity, Belonging, and Rediscovering God” (Brazos Press, 2020), by Kaitlin Curtice. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.

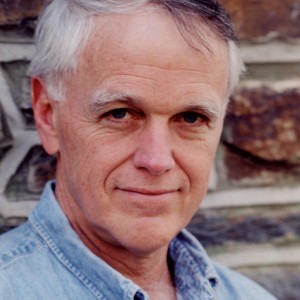

Clyde Edgerton grew up in a family with 23 aunts and uncles and was inspired to be a writer after hearing Eudora Welty read “Why I Live at the P.O.” What he heard in that story was the beauty and simplicity of the particular details that create relationships between people. His nine novels are filled with this kind of Southern storytelling.

Edgerton, who teaches at the University of North Carolina-Wilmington, has been a Guggenheim Fellow and is a member of the Fellowship of Southern Writers. Three of his novels have been made into movies and five have been listed as New York Times Notable Books. The plot of his first novel, “Raney,” revolves around the marriage of a Free Will Baptist and an Episcopalian. His latest book is “The Bible Salesman,” about the adventures of a Bible salesman and a car thief.

Edgerton spoke with Faith & Leadership about storytelling and imagination, teaching and preaching and about the fascination of relationships that continue to inspire his own writing.

Q: How should Christian leaders approach storytelling?

I think they should look at the parables of Jesus.

Q: Why?

Because the parables of Jesus are fascinating in that they often talk around a subject. They can be interpreted in different ways sometimes. And they usually are not telling you what to do or not to do.

Leaders tend to think that that’s their job to tell people what to do and what not to do. And you would think, if we look to someone like Jesus as a leader, there clearly are places where he tells you what to do and what not to do, but there clearly are places where he illustrates with a story. So I think illustrating with a story can engage.

Storytelling assumes uncertainty. Storytelling assumes that the other person is involved. When you tell a story you’re using your experience — when you’re telling a story that you made up — your experience, your observation, what you know about and you’re using your imagination. And when you tell that story, it lands on another human being who has his or her own experience, his or her own observation and knowledge and his or her own imagination. So it might not be the same story that left your mouth. And if you recognize that, life is much more exciting.

And I think that’s one of the truths about the parables of Jesus. They land on different sets of imaginations. So leading through a story recognizes right away that the way we are designed and made up is variable from one to the other. So, to order proclamations and directions may not set well and may not be as effective as storytelling.

But storytelling assumes story listening. By that I mean when I deliver my story, that might not be the end of it. Why should I not have a story told back to me and in doing so find out that my story did not work the way I had anticipated it? And thus I need to tell another story. Where I’m coming from, two-way communication is helpful in leadership.

Q: You’ve developed a philosophy over the years. I can’t remember the actual quote…

About teaching? “Teaching is the act of inducing students to behave in ways assumed to lead to learning.” It fits in all kinds of little situations. For example, I think preaching is the act of inducing parishioners to behave in ways assumed to lead to “blank” — whatever you’re trying to get them to do. It turns out that it’s behavior that influences behavior in this business of instruction.

It grants that we don’t know all that we might know about learning, and it assumes that you learn from your own behavior.

Q: But you can’t see your own behavior.

You can see the consequences of it. You can feel the consequences of your own behavior. And you may learn facts or from other people — say, the world is round, so you learn that. But given an opportunity to learn how to survive in the world or in the wilderness, a little piece of the world, you will learn from your own behavior, your own guided behavior, perhaps.

Q: Do you go to church?

I’m undergoing a transformation in regards to the Bible. I grew up in a fundamentalist family in church, in which there were loving, wonderful people and wonderful music. But the theology, the idea of heaven and hell and good behavior and bad behavior and the way it was all presented to me was such that I rejected it and I still do. And it was hard, and it has been hard, and this is true of so many people for sure, to realize that there may have been some baby in that bathwater they threw out.

So recently, my wife and I — because we felt a nagging need for it — we’re back going to church. And it’s been a revelation for me. First of all it’s been really great to know, to meet a preacher, [the Rev. Eric Porterfield, senior pastor at Winterpark Baptist Church in Wilmington, N.C.] who seems to be broadminded.

It’s an amazing kind of thing to talk about, which is so divorced from what it is to live it. There’s so many ways of looking at it. I try to come up with simple definitions in my own mind about why I’m doing what I’m doing.

My preacher and I have breakfast or lunch about once every two weeks and it’s so exciting for me to talk about these topics with someone who seems to be — most of the time — not as skeptical as I am but almost as questioning as I am. It’s so refreshing.

[The community] is important because it inspires the individual. You’re around other people and you get inspired and so therefore you behave differently

Q: How is your work tied to both tradition and innovation?

Well, I think in just about any field, you have people who come in with a lot of passion and create quite a stir. But they don’t know what the hell is true about their tradition. They don’t have a feel for failures and successes in the thousands of years prior.

Faulkner said experimental writing or innovative writing, or whatever, is 90 percent traditional and 10 percent experimental. That’s when it works as experimental writing. So I believe in a constant movement based in conflict and fights and confusion and discussions about what has gone on in the past. But you’ve got to know what’s gone on in the past in your particular field.

But for me it’s always enthusiasm and passion about your topic, which will take you back to the traditional stuff and will also make you curious. That curiosity, which embraces uncertainty, for me, is a secret.

And I get this — embracing of uncertainty and the wisdom of uncertainty — from Milan Kundera, who in “The Art of a Novel” talks about the fact that Don Quixote can be seen as wise or foolish. And that balance is very human. It’s very much how we were made. We were made to ask questions. But you can’t ask questions if you’re certain.

So you have a leader who knows everything but is not inspirational because there’s that spark missing, I think. Which, again, some experimental “leaders” have but they don’t know anything about the tradition of their field.

Q: Let’s talk a little bit about writing in terms of your process. How do you get that inspiration and sustain it through?

For me it’s not very different from a lot of what we’ve been talking about. And that is the goal in my writing is to find a couple of characters or more who have a relationship, which I find interesting, sometimes fascinating, sometimes awe-inspiring. If I can get a couple of characters who get into something that I can follow along and have a part in molding and watching, to me that’s interesting. But there are a lot of problems to solve to get there. If I’m lucky it’ll have a life of its own. That’s what keeps me doing it, I think. I feel like I’m more of a translator than an inventor as a fiction writer.

Q: Is that different from what inspires you about teaching?

It’s kind of separate. I can’t do anything about [students] becoming inspired. I have to assume that they already are. But I can help them cut some corners. I can teach them that which will enable them to reach their potential, almost reach their potential a year or two earlier than they would have otherwise. And it’s fairly easy. It’s not like some unsolvable kinds of jobs that people have and don’t see the result.

For example, preachers I would think often work for something that’s not quite clear. And when they don’t see results it’s disheartening. You don’t quite have that feedback, for example, like you do in flying an airplane or playing music. You hear it’s really bad or people don’t applaud or they do applaud with music. With flying you crash or you don’t crash or you bounce in landing or you don’t bounce the landing.

I watched Eric preach a wonderful sermon and the audience was just so quiet. I wanted to say, “Amen” or “My, my” or something. So finally he said, “Do I hear an Amen?” And there was this little sprinkle of amens here and there and he said, “I didn’t hear that. Can I hear that a little louder?” So as loud as I could I shouted “Amen!”

I had been ready to do that for a long time.