Living into the kingdom of God by believing in its abundance

My daughter has entered a phase of development where she is starting to be more inquisitive about the customs and practices of our household. In this stage, she is starting to ask me simple but challenging questions about my faith.

As a “preacher’s kid,” she is accustomed to seeing her father preach Sunday after Sunday. Her awareness of the sermons has become more evident through her parading the preaching moment, running through the house shouting, “Yes” and, “Help me, Holy Ghost” — key phrases that I use when sharing the word with my congregation.

Recently, when talking about worship, my daughter asked me a question that I was not expecting. In our conversation about my sermon for that day, she asked, “Do you believe it?”

That particular Sunday, I had spoken about the faithfulness of God as seen through God’s abundance in the development of the early church. Luke, in the book of Acts, recounts a moment when

the whole group of those who believed were of one heart and soul, and no one claimed private ownership of any possessions, but everything they owned was held in common. With great power the apostles gave their testimony to the resurrection of the Lord Jesus, and great grace was upon them all. There was not a needy person among them, for as many as owned lands or houses sold them and brought the proceeds of what was sold. They laid it at the apostles’ feet, and it was distributed to each as any had need. (Acts 4:32-35 NRSV)

In this display of Christian community, the people were so compelled by the grace of God that they became living instruments of the sign and foretaste of the kingdom of God. They denied themselves ownership and became stewards of resources that could be used to address the needs of people. I was challenged by my daughter to answer whether I believed this to be true.

Peter Storey made the claim in a 2021 lecture titled “10 Markers of Prophetic Ministry” that one does not choose prophetic ministry; it lays itself on you. Prophetic ministry rises out of a form of pastoral ministry that engages the least and the lost.

Luke provides a vivid description of what it means to care in a prophetic manner for those in need. The early church believed so much in the imminent arrival of the kingdom of God that they began developing customs and practices that served as glimpses of that kingdom.

Do Christians still believe that we are called to usher in the kingdom of God? Are our contemporary organizations and institutions willing to forsake ownership, or the need to control, to become communities and congregations that are meeting the needs of the oppressed? If so, how does that shape our thinking about ministry in our context? Do we believe that we have the capacity to be stewards of resources in a way that displays God’s abundance?

Mark Elsdon, discussing his book “We Aren’t Broke: Uncovering Hidden Resources for Mission and Ministry,” has said, “If everything we have is what God has given to us to be stewards of, is really the best use — the highest and best use of that money — to generate as much money as possible? Or might it be to generate as much good as possible?”

As Christians, we are to work for the good of the people. Christian leadership is different from any other form of leadership, because we believe and we confess that we can be the instruments of the foretaste of the kingdom of God. Therefore, our customs and our practices tend to be countercultural.

Scarcity is not in our vocabulary. However, when we are good stewards of the assets we have been blessed with and we cultivate an environment of faithful stewardship, we get a glimpse of the abundance that dwells in our community.

Too often, we think we must own the resource to operate the resource. However, we are surrounded by abundance, especially when we work together. The people in need did not have ownership, but they had access. We, as well, do not have ownership, but God has given us access to a host of resources that are meant to be used for the good of the people.

Our ministries should begin to think in terms of being catalysts to inspire others about how we can utilize resources we have access to for the good of the people. That we might not own the resources does not mean that the resources are not in our community. What if we got outside the boundaries of our institutions or even the mindset of ownership and, seeing the assets of community, cultivated a culture of generosity?

Glory is not meant for our institutions but for the God we serve. We do not need to get credit — our greatest testimony is to be a part of the transformation. As my daughter asked me, Do you believe it? Do we believe it?

Luke provides a vivid description of what it means to care in a prophetic manner for those in need.

By late September 2022, as the senior pastor of Great Hope Baptist Church in Richmond, Virginia, the Rev. Melvin F. Shearin II had worked every Sunday since the beginning of the year.

Although he was hired as a full-time pastor seven years ago, and he views this work as a calling, he has found that his compensation does not fully cover health care and other essentials.

So in addition to his standing duties as senior pastor, Shearin has taken on additional employment. Over the years, he has worked as a call center manager and at a local gym and has even started his own travel business, to ensure that he can meet his financial obligations.

Bivocationalism is not a modern phenomenon, especially for pastors in historically Black churches and those that serve Latino and immigrant populations. According to the 2021 report of the National Congregations Study, one in three congregational leaders (35%) is bivocational, and one in five (18%) serves multiple congregations. And the number is growing as congregations shrink.

“Seeing pastors doing part-time ministry is nothing new. It goes back, of course, to biblical times and the apostle Paul being a tent-making pastor,” said the Rev. G. Jeffrey MacDonald, the author of “Part-Time Is Plenty: Thriving Without Full-Time Clergy.”

MacDonald, who himself works as a reporter, consultant and United Church of Christ pastor, pointed also to Peter and other disciples — fishermen who left their nets to follow Jesus but still continued to fish.

In fact, even in more affluent countries, it’s only been during the last couple of centuries that it became more common to have one pastor full time in one local setting, MacDonald said. It wasn’t affordable until congregations started to have more wealth in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

These days, pastors may choose bivocationalism for personal reasons, such as pursuing a second calling or career by choice, but also for economic reasons, out of necessity. That can be difficult for pastors and congregations that regard bivocationalism as a sign of failure.

“An unstated concern is often stigma. North American churches are shaped by a full-time bias, supported by the beliefs that money equals success and bigger is better,” noted the Rev. Dr. Darryl W. Stephens. He is the director of the Pennsylvania Academy of Ministry, an ordained deacon in the United Methodist Church and the editor of the book “Bivocational and Beyond: Educating for Thriving Multivocational Ministry.”

“Even in traditions in which bivocational pastorates are the norm,” he said, “people often measure themselves and their churches against a full-time ideal.”

Bivocationalism as an economic necessity

The context for decisions to be bivocational can vary, but economic pressure is part of the picture.

In the United States, the mean annual wage for clergy is $57,230, and the mean hourly wage, $27.51, according to 2021 data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (Some mainline denominations set salaries for their clergy, while others do not.)

Pastors’ salaries have remained stagnant or declined compared with those of other helping professionals like social workers and teachers, said Elise Erikson Barrett, the coordination program director for the National Initiative to Address Economic Challenges Facing Pastoral Leaders, an initiative of Lilly Endowment Inc., hosted by the Center for Congregations.

Church membership has continued to slip, and the pandemic has many church leaders feeling uncertain about the economic picture. At the same time, inflation has skyrocketed, with consumer prices seeing their largest increase in 40 years in June 2022, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Some churches have adjusted their budgets, and more pastors may find that a second or even third job is needed. But context for these decisions varies.

Do you think of bivocational ministry as “less than” full-time ministry? If so, what might change your mindset?

For instance, in a setting where divinity school is required for ordination, seminary debt can be the pressing economic issue, Barrett said. While concerted efforts are being made to reduce the cost of a theological education, the U.S. student debt crisis can affect pastors in the same ways it affects the rest of the population, she said.

In a setting where a master’s degree isn’t required but a church’s budget doesn’t offer a benefits program, “it may be medical debt or health care that’s the presenting economic issue,” she said.

And pastors who are female, as well as pastors of color, are more likely to be in low-income, small or rural congregational settings, Barrett said.

How might having a bivocational pastor benefit both the clergyperson and the congregation? What might be the losses?

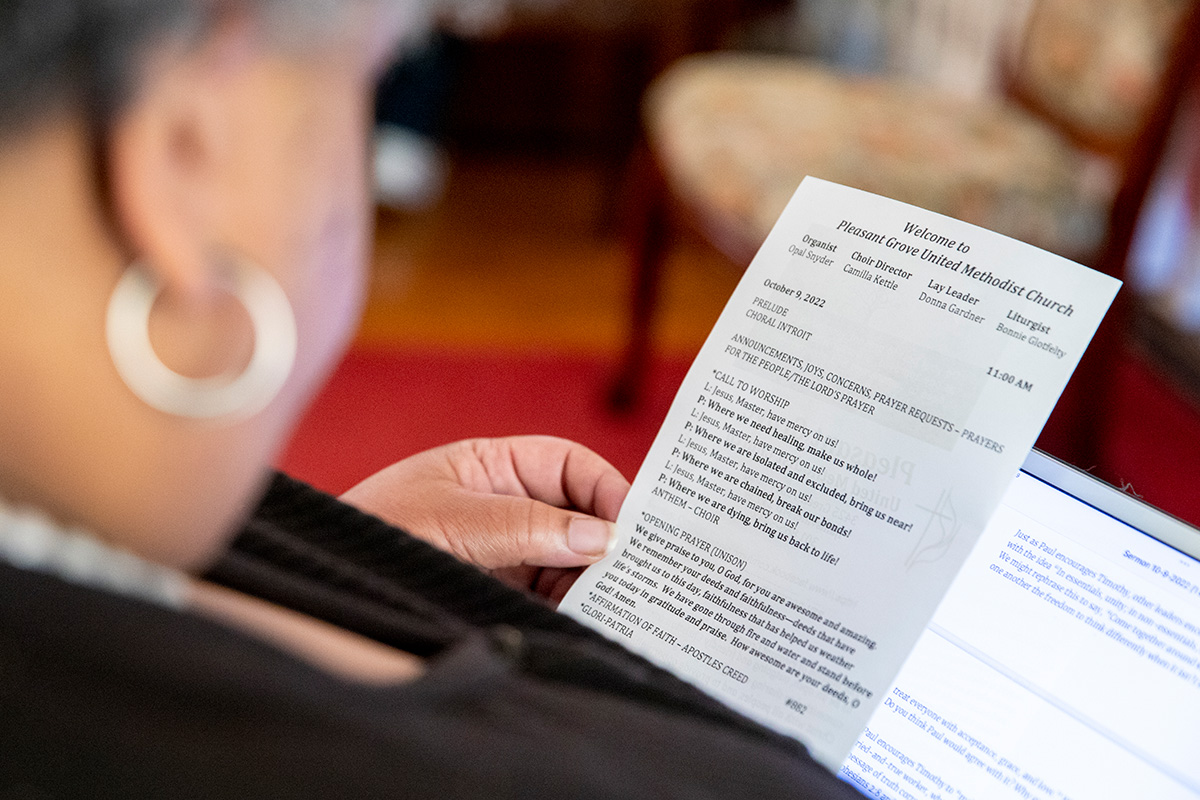

The Rev. Rochelle S. Andrews is the senior pastor at Pleasant Grove United Methodist Church in Ijamsville, Maryland, as well as the associate director of the Center for Public Theology at Wesley Theological Seminary.

She said she appreciates both of her jobs, because they appeal to her passions, but acknowledged the economic side of bivocationalism for many Black pastors. Andrews, who is ordained in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, noted that redlining and other systemic racism is a reason many Black churches still don’t have the same resources as some of their white counterparts.

Given this history, white churches would do well to look outside themselves for guidance in considering bivocational ministry, MacDonald said. “This is an extremely rich area for predominantly white churches to learn from churches that have a different racial and ethnic mix, because the experience and know-how is largely vested in the Black, Asian and predominantly immigrant churches.”

Mindset matters

Many long-term bivocational pastors do consistently manage and balance their roles. But for pastors accustomed to being fully funded through singular positions, bivocationalism can feel like a shock.

These pastors’ challenges can be emotional and psychological when they move from only serving at church to having to clock in elsewhere, said the Rev. Dr. Ira E. Antoine Jr., who works as both an ordained Baptist minister and the director of the Bivocational Pastors Ministry for the Baptist General Convention of Texas.

Still, people considering bivocationalism should look at what they are gaining, Stephens said, and not regard it as a loss.

“In some ways, [bivocationalism] is liberating. Freeing. I get to set my own schedule in many ways. In other ways, I’m constantly running up against that full-time bias in my own mentality,” Stephens said.

“I have to remind myself that I’m good at what I do, that I’m called to teach — in my case, my ministry is teaching, research and writing — and that I’m not defined by my paycheck. And I have to keep reminding myself of the advantages of being bivocational, the flexibility and things like that.”

And though pastors may sometimes feel “less than” if they are bivocational, or that a congregation is somehow “less than” because its pastor has to have two jobs, “we’re trying to change that course and that mindset,” Antoine said.

The Christian Reformed Church in North America has begun offering one of many experiments in bivocational ministry, in this case providing a yearlong Bivocational Growth Fellowship to folks considering a change. It provides financial support, resources and a peer group to help with the discernment process. The fellowship is part of a larger CRCNA project called Financial Shalom, funded by Lilly Endowment Inc.

The first cohort convened in 2021. Thirty-five pastors have taken part so far. Monthly gatherings on Zoom, hosted by a longtime bivocational pastor, offered participants a chance to talk with entrepreneurs, people pursuing a “side hustle” and financial planners, among other guests.

Some participants were already working and planting a church, some were right out of seminary, and others were considering a switch from full-time ministry.

“[Bivocationalism] doesn’t work for everybody, but for those who did it, having the group of peers together was the big win,” said Zach Olson, ministry vocational consultant at the CRCNA.

Who in your life could advise you about managing a transition to bivocational ministry? Are there people within or outside your denomination or tradition who could share their wisdom?

Advice for pastors considering bivocational ministry

For pastors considering bivocationalism, whether it’s by necessity or because they feel called to it, there are key steps to take, experts and practitioners say.

Secure a flexible second vocation. In today’s digital world, where so much work can be done remotely, there is room for bivocationalism for pastors, said MacDonald, the pastor and journalist.

Pastors should understand that carving out a second vocation is possible, but they should also ensure that it fits into their lives. For instance, if a pastor prizes being physically present at church on a regular basis, a second job with a long daily commute may not be a good fit.

In addition, if pastors are seeking an outside job where they would report to a supervisor — as opposed to setting their own tasks or hours by working as an entrepreneur, consultant or freelancer — they should ask questions about expectations, duties and the work schedule during the interview process.

Shearin, the pastor of Great Hope Baptist Church, said this is an important step because there may be tasks that aren’t included in the general job description. Shearin also advises asking whether the job will provide “wiggle room” to do funerals, weddings or other church events.

He said the crucial question for pastors is, “Can you find a job that’s willing to work with you?”

Communicate with the congregation. Oversight of second jobs can vary, with hierarchical churches potentially requiring approval of the bishop if the pastor or priest is to work outside the parish, MacDonald said. But whether or not pastors need this approval, communicating with the congregation about the situation — and getting buy-in — is a good idea.

“So much of this going well relies on a healthy, mutually respectful and mutually caring relationship between a pastor and the congregation, where economic issues can be discussed honestly and openly and without blame and shame,” said Barrett, the coordination program director for the National Initiative to Address Economic Challenges Facing Pastoral Leaders.

There are many ways that bivocationalism can work, but adaptation can be hard, she said. “The thing that can make it life-giving is that healthy relationship and a shared vision for why we’re even doing this in the first place.”

Acceptance from the congregation can be essential to a good experience.

“The success of bivocational pastorates hinges, in large part, on the ability of the congregation to embrace an understanding of ministry that differs from what they may have been taught to expect, at least in predominantly White, mainline Protestant traditions in North America,” Stephens wrote in “Bivocational and Beyond.”

Setting clear boundaries is also a good idea, MacDonald said, noting that churches can confirm expectations by drafting a new contract to describe the responsibilities of both the pastor and the congregation.

“In a church where they really understand that you are their part-time pastor,” Andrews said, “they recognize that you have a life outside, other than them, and you just find a balance.”

How might you approach your congregation about discerning whether to move to bivocational or part-time ministry? Would they embrace an understanding of ministry that differs from what they might have expected?

Plan ahead and practice good time management. When pastors have two (or more) sets of professional obligations, planning and time management are essential — especially since a second job can be exhausting.

To help with organization, Antoine, who has two full-time jobs, said pastors should plan their calendars as much as a year in advance, blocking out key professional and personal events such as vacations, holidays, scheduled commitments (when known) and more.

They should also determine how much time, on average, they need to dedicate to each job to do each one successfully, then plan their days accordingly. And though unexpected events do happen, it can be helpful to talk with church staff and members about their desired schedules, said Antoine, who is with the Baptist General Convention of Texas as well as serving as a pastor.

Embrace remote work, self-care and help from others. All can be important to avoid burnout.

Andrews said a difference for bivocational pastors is that they may not physically be at the church office every weekday. But there are other ways these leaders can show care for their congregations.

For instance, Andrews said her church members can call her cell anytime (she texts back if she can’t answer). She does Bible study Tuesday nights via Zoom, and she continues to preach in person on Sundays.

“As a part-time pastor, find the ways you can be present for them, so that when there may be times you can’t because something comes up, they don’t feel it,” Andrews said. “Hearing them, listening to them, really, really goes a long way.”

Pastors also can do tasks like planning sermons and the order of worship (as Andrews does weekly) while off-site.

Pastors don’t have to be all things to all people, Antoine said, noting that it’s OK to delegate some tasks. After working 40-plus hours per week at his staff job and 32-40 hours per week on the church side, he planned a sabbatical from church this July and synced it with two weeks of leave from his second job.

“Self-care must be intentional, and you have to overcome the guilt,” he said.

Depending on the activity, laypeople, elders or other church staff can pitch in. Perhaps a layperson can do certain outreach activities, or a church elder can select hymns. Some theological or sacramental duties are those of pastors alone, MacDonald said, but clergy certainly don’t have to do everything themselves.

Be open to the joys and benefits of bivocationalism. Of course, this orientation may be easier if the pursuit of bivocationalism is a choice as opposed to a necessity. But either way, benefits can be more than economic. They also can include being in a position to help more people, widening a professional knowledge base and living out a calling — or callings.

For example, MacDonald, who has worked as a pastor and journalist for more than two decades, has been able to both research bivocationalism and practice it, he said. When he learned he could serve a church and continue his prior profession, it was exciting, he said.

“I learn stuff in journalism all the time that I will refer to in a sermon, and it’s a blessing. It’s a benefit to the congregation,” he said. “I’m a more interesting pastor because I move around and interview interesting people.”

Andrews also said that her job offers new chances to connect with community members and leaders. And seeing a pastor with a second job can help community members better relate to these faith leaders, she said.

“This is a real opportunity that’s opening up,” MacDonald said. Instead of limping along, he said, bivocationalism can be a liberating way for laypeople to spread their wings in ministry and for the church to establish community partnerships.

And, he said, it can allow pastors to become “more stable, more stimulated, more creative, have more to offer to your church and really find that this may be a great blessing to the pastor as well as to the congregation.”

Burnout is an issue for pastors, whether they have one job or more. How might you manage bivocational ministry so that you don’t burn out?

Questions to consider

- Do you think of bivocational ministry as “less than” full-time ministry? If so, what might change your mindset?

- How might having a bivocational pastor benefit both the clergyperson and the congregation? What might be the losses?

- Who in your life could advise you about managing a transition to bivocational ministry? Are there people within or outside your denomination or tradition who could share their wisdom?

- How might you approach your congregation about discerning whether to move to bivocational or part-time ministry? Would they embrace an understanding of ministry that differs from what they might have expected?

- Burnout is an issue for pastors, whether they have one job or more. How might you manage bivocational ministry so that you don’t burn out?

Don’t be misled by the makeshift counter and tent outside Humphreys Street Coffee Shop in Nashville, Tennessee. The business is here to stay.

That renovated green house is a symbol of permanence, commitment and determination. After all, helping people understand their value is not quick work.

As a social enterprise of Harvest Hands Community Development Corporation, the coffee shop serves up more than cold brew and lattes; it provides jobs, mentorship, discipleship and skills for teens from the community nearby.

“We don’t hire students to make coffee,” Harvest Hands executive director Brian Hicks likes to say. “We make coffee to hire students.”

On a hot, humid August afternoon, local residents pull up or stroll over in a steady stream. One speaks of how he likes both the coffee and the aesthetic. On the edge of a recently gentrified neighborhood, it’s charming, inviting. And powerful.

In a non-COVID season, Harvest Hands has met community requests for after-school activities, sports leagues, leadership training and more. Founded in 2007 by Hicks and his wife, Courtney, the organization has grown from a neighborhood gathering of a dozen or so kids to a nonprofit that brings in $500,000 a year in coffee roasting, brewed coffee and handmade soaps, in addition to gifts from individuals, churches and foundations.

Does your organization have empty spaces that could be re-imagined into a way to serve your community in this season?

There are typically 10 full-time staff and up to 50 more in various part-time roles — including those students. In the wake of COVID-19, the shop is currently curbside and delivery only.

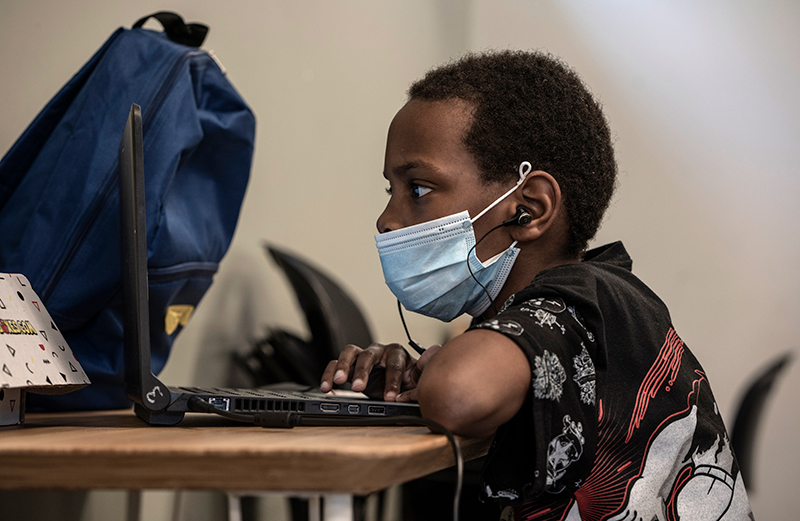

After-school programs are shuttered for now, coffee and soap production continues with just a handful of students, and the once-bustling community center has transitioned to a quiet, safe and internet-ready space for younger children to take part in remote learning.

But the undercurrent of digging in for the long haul remains.

“Numbers are important,” said William Parker, the Harvest Hands director of youth and mentoring. “But they don’t dictate success.”

‘What do you love about your neighborhood?’

It was the Rev. Howard Olds who drew Hicks from Kentucky to the neighborhood. Olds was the longtime pastor of Brentwood United Methodist Church, an affluent congregation in an adjacent county. He was interested in neighborhood revitalization in South Nashville, not far from downtown; the church had the resources but not the manpower for the work.

Hicks, a seminary grad who cut his social activism teeth working in inner-city Philadelphia, Chicago’s South Side and Louisville, was hired by the church to lead the nonprofit. As the organization grew, all other staff would be funded through Harvest Hands and represent a variety of denominations, experience and education.

Hicks had been further inspired by the writings of John Perkins, co-founder of the Christian Community Development Association, and was ready to see communities empowered through true partnership rather than charity. He was ready to put down roots.

Olds, meanwhile, had attended a community meeting and was told that if he really wanted to make a difference, the church should buy the drug house on the top of a neighborhood hill.

Traditioned Innovation Award Winner

Leadership Education at Duke Divinity recognizes institutions that act creatively in the face of challenges while remaining faithful to their mission and convictions. Winners received $10,000 to continue their work.

“So they did,” Hicks said. “He didn’t ask the congregation, which was made up of CEOs and leaders. He told them. And that became the entry point.”

The house was torn down, and a fall harvest festival was held on the lot.

“The price of admission was a survey,” Hicks said. “We asked them, ‘What do you love about your neighborhood? And what would you change?’”

The residents were concerned about kids with nothing to do but get in trouble. An after-school program was a simple ask.

The newly formed Harvest Hands bought a small house and started working with children in 2008. It had outgrown that house by the following year, and the Methodist Church donated the building — the former Humphreys Street UMC — that would eventually become the coffee house. But things were just getting started.

Ruben Torres, an introverted middle schooler who would hunch over and fold into himself as if he didn’t exist, was already part of the Harvest Hands program. Hicks saw promise in Torres and asked whether he might be interested in a new opportunity.

He could learn how to roast coffee, “a grown-up, adult thing that was super exciting,” Torres said. Harvest Hands was looking for a social enterprise that would engage teens; a paycheck would be a definite draw.

Whom do you need to invite to get involved in your community’s mission in a new way?

The church provided an introduction to one member in particular: Cal Turner Jr., former chairman and CEO of Dollar General. Hicks asked Turner for not only a Diedrich coffee roaster — a high-quality machine geared toward specialty batch roasting — but also a trip to the company’s Idaho headquarters for himself and one other to learn how to use it.

“That’s like learning to drive from Henry Ford,” Hicks said. Turner told the then-30-year-old Hicks to write a business plan and he’d make it happen. Hicks enlisted the help of the teens. After a few tweaks here and there, Turner held true to his word.

Torres was chosen for the trip. Today, he’s production manager and head roaster, overseeing teens not unlike who he once was. Harvest Hands, he said, helped him learn about his value as a person.

“Something we very much believe in is that everybody in the community has the potential to be greater,” Torres said. “There are also people who have the potential to be leaders. The talent is there. There’s no need to bring a whole bunch of external factors.”

It is easy to default to bringing in trusted external experts to start something new. What potential is already present in your community waiting to be invited to contribute?

He considers himself fortunate to have had an “awesome support system and great parents.” His mother, Jael Fuentes, is now soap production manager at Harvest Hands. But Torres also understands he’s in a position to model change, leadership and motivation for others. His own experience lends credibility.

“They take things to heart from me,” he said. “As opposed to saying, ‘You don’t know my life.’”

Giving it back to the people

As coffee and soap production grew, the Wedgewood-Houston neighborhood began to gentrify.

“The first thing we did,” Torres said, “was to invite the community members in and say, ‘What do you need? What do you see?’”

With housing costs rapidly rising, many were being forced out.

By 2015, Harvest Hands staff knew they needed to relocate. They met with members of the Napier-Sudekum neighborhood, less than a mile away, and learned of the need for after-school programs there, too.

Naturally, there were new challenges. Napier-Sudekum has more than 800 government housing units; crime rates and violence are high, and Harvest Hands notes that the average annual household income is $6,500. But it is also a community in which neighbors look out for each other and untapped talent is overflowing. Hicks found an old warehouse perfect for a community center and set to work.

“It was the craziest thing,” he said. “We beat the realtors and the developers to the building. As much as gentrification pushed people out, it drove up the price of that original crack house lot [in Wedgewood-Houston].”

The property that Harvest Hands had bought for $275,000 was sold to developers for $2.3 million, with plans to add shipping container units for “affordable” housing. The funds from the sale have been given back to the people, in essence, as Harvest Hands continues to expand its reach.

“It’s creatively using gentrification for justice,” Hicks said.

A call to reform

The bright and spacious community center in Napier-Sudekum officially opened in 2016. Named for Olds, who died in 2008, it is adorned with colorful murals and words like “integrity,” “compassion,” “love,” “courage,” “respect” and “wisdom.” There’s a playground and a large lab-like room that now houses two coffee roasters, stacked bags of coffee beans and packaged handmade soaps.

What do the spaces your organization inhabits communicate to others? How do you cultivate a space in which people feel valued?

As one of the first craft roasters in Nashville, Harvest Hands had steadily built a following that has helped sustain the organization through the pandemic. Online sales through its website include coffee from Africa, Central America, South America and Southeast Asia, in addition to liquid and bar soaps, laundry soap and a coffee sugar scrub. The brick-and-mortar coffee shop on Humphreys Street opened in 2018.

When people visit the Howard Olds Community Center, Hicks said, they often seem surprised at just how “amazing” it is. “Several things go through my mind — first, do you think these kids should not have a great space? Is it supposed to be a dump? We try to help kids believe that they are valuable and they are worth it.”

Jessica Holman, the organization’s senior director of employee and community relations, grew up in the area and came to work at Harvest Hands while in graduate school at Vanderbilt University close to a decade ago. She knows firsthand that local residents have “inherent talents and skills,” she said. “They just need opportunities to let them shine.”

“I wish that people knew the people in these communities,” she said. “There are some amazing people here. Intelligent. Creative. And I wish people knew about the sense of community here, too.”

Consider Jarica Sanders, a self-employed artist, hair braider and mother of three. Her kids, ages 7, 8 and 10, have taken part in Harvest Hands programs for several years. They’ve played a variety of sports with the organization, participated in after-school programs, learned life skills, been encouraged in their faith and are now going to the community center for virtual learning. Sanders is hoping her oldest son, Lemy, will be able to gain work experience through Harvest Hands when he’s older, too.

In her Napier-Sudekum neighborhood, she said, “if you don’t know about Harvest Hands, I don’t know where you’ve been.” And it’s not just the activities and opportunities for the kids. Sanders said the organization has a reputation for truly partnering with residents.

“We have parent meetings at Harvest Hands,” she said. “They give us the chance to come in and tell them what’s working and what’s not working and what they could do better. They get the community involved, and I really like that. A lot of programs, they just come out and say, ‘We have this, this and this.’ But the people at Harvest Hands actually take the time to say, ‘What do you need? What do you think can we add?’ That’s a very big help.”

Harvest Hands follows the tenets of asset-based community development, which include focusing on those strengths, gifts and talents already present rather than just working to “fix” what’s wrong.

How much of your organization’s work is “fixing” what is wrong, and how much is building upon the strengths, gifts and talents already at work?

Parker, a Memphis minister who came to Harvest Hands in January, said those concepts had always been part of his story; he just didn’t know them by that name.

Learning about the powers that systemically oppress communities — especially communities of color in urban environments — tugged at his heart. So did the opportunity to continue his work with teens.

“It’s not enough for me to just believe that Jesus Christ has changed the world through his actions,” he said. “That same spirit that is in Jesus is in me, and it’s calling me to bring reform, to change, to be with the community and say that it doesn’t have to be this way. The gospel is more than just the theological ideology that we hold that sounds good on Sunday mornings. It calls for social reform to be in the mix.

“I’m just trying to lean into that social holiness piece and say, ‘OK, justice is really close to the heart of God.’ If I want to be able to understand how faith is played out in communities, I need to be in a position to hear stories and say, ‘Where is God in that story, do you think?’ … What drew me to Harvest Hands was to have space to ask the big questions without attempting to fix anything. That’s where real healing takes place, where people are brought back to themselves.”

Living Jesus out loud

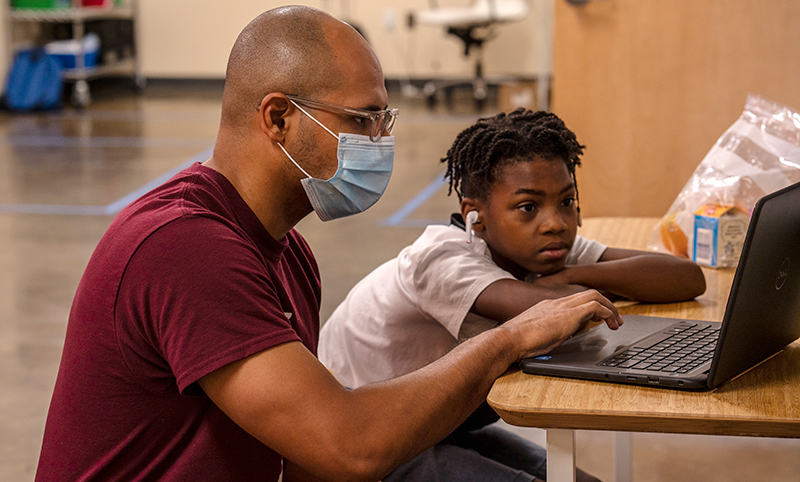

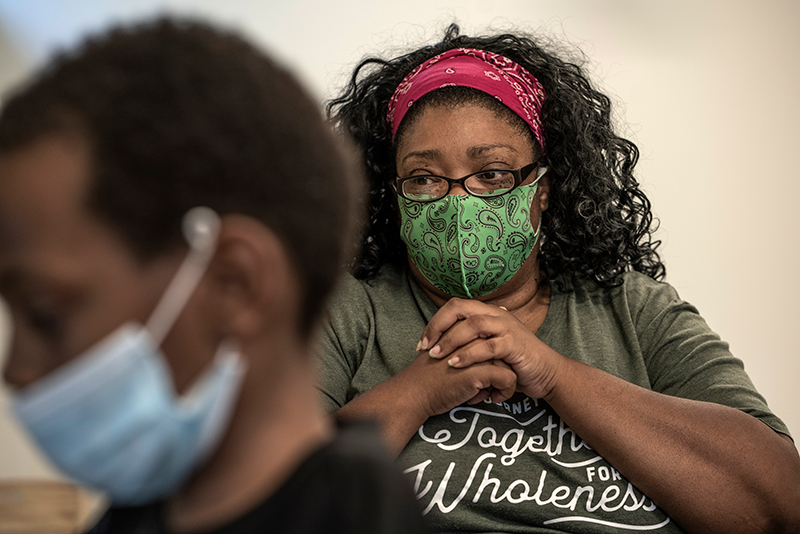

That same hot day that customers were lining up for coffee at the shop, Parker was sharing a classroom in the community center with a middle schooler taking part in remote learning; the city’s schools had not yet opened for in-person classes because of COVID-19.

Across the hall, Chartrice Crowley, the director of elementary programs, had a handful of younger students of her own. The kids have been on alternating days from 7:30 a.m. to 1 p.m., mindful of social distancing limits, with sibling schedules matched to ease the burden for parents.

This effort, too, came from going to the community and asking rather than assuming what was needed. It is the difference in saying, “We are here for you, not because of you,” Parker said.

How might your organization’s work be different if it existed “for” people rather than “because of” people?

In more normal seasons, Crowley plans after-school enrichment opportunities like African drumming and ballet, homework time, personal development, fun, and a faith component. Harvest Hands allows her to “live Jesus out loud” in a way that working in a public school would not.

“The thing that makes me most proud about working here is that I get to see the fruits of the seeds that have been planted,” Crowley said. “I get to see greatness every day. These kids are amazing. They’re fun. They’re witty. They’re smart. They blow me away every day with what they know.” Even when they’re figuring out learning through a screen.

There’s a cultural element to Harvest Hands, too, one that opens doors of opportunity, knowledge and respect for the predominantly Black community. Classrooms, for example, are named for historically Black colleges and universities, with those names changing each semester to increase exposure.

“Students are placed in their ‘house’ at the beginning of each semester,” Holman said, “and they participate in house games throughout the semester, where they are able to win prizes. We think it’s important for our students to know the history of HBCUs, why they were created, and that they are an option for them to further their education. It’s important that they learn about Black excellence at an early age so that they grow up learning that greatness lies within them.”

Local street artist Charles Key serves as another inspiration; his work can be seen throughout the community center (as well as at various Nashville sites). There are portraits of lesser-known Black leaders — many of them from the area — on the walls of the middle school classroom.

Overall, the ongoing uncertainty of COVID-19 makes some aspects of the future unclear. What is clear is that Harvest Hands will keep asking the community what it needs and endeavoring to incorporate the resources available to bring it about.

Torres hopes to develop a roasting certification program for the students he oversees. Hicks is looking forward to hallways full of kids once again. Parker is exploring pathways to success for high schoolers. And Holman will keep seeking opportunities to tell the story of long-term vision and sustainable success.

As for others hoping to do the same? Holman suggests that they’d do well to check their “why.”

“Will you be there for the long haul, willing to relinquish power to the people within the community and let them shape it?” she said. “Our goal, at the end of the day, is to work ourselves out of a job. If we’re doing what we aspire to do, that means the community will lead. Then they’ll be the ones out there doing what needs to be done.”

Questions to consider

Questions to consider

- Does your organization have empty spaces that could be re-imagined into a way to serve your community in this season?

- Whom do you need to invite to get involved in your community’s mission in a new way?

- It is easy to default to bringing in trusted external experts to start something new. What potential is already present in your community waiting to be invited to contribute?

- What do the spaces your organization inhabits communicate to others? How do you cultivate a space in which people feel valued?

- How much of your organization’s work is “fixing” what is wrong, and how much is building upon the strengths, gifts and talents already at work?

- How might your organization’s work be different if it existed “for” people rather than “because of” people?

What does having a financially sustainable ministry mean? The one-size-fits-all answer is simple. The revenue coming in is consistently more than the expenses going out. But this simple answer obscures the gap between those benefiting from generations of building wealth and those in Black and brown America who have had wealth stolen across the years. Calculating sustainability needs to account for this gap.

I hope that the current pandemic, economic recession and renewed attention to racial inequity is teaching those in the dominant culture that one size does not fit all. When “we” talk about money, the field is never level.

African Americans were treated as property for generations while white Americans were acquiring land and accumulating money. The starting places for families in these communities today is not equal. Whenever we discuss financial sustainability, we have to examine the conditions that create, or that make it difficult to create, wealth.

Sustainability is a sought-after goal in new-program development. In financial terms, it refers to developing revenue sources that provide funding to keep the program going. Sometimes it is as simple as one funder asking the program to find other donors. Sometimes it means adding fees to the service or getting somebody else’s budget to pay the cost. Often it includes reducing the cost of the service to match the expected revenue.

As a white leader in a dominant-culture organization, I hear the talk about making adjustments and raising more money — and it all seems doable. The pandemic has thrown up a roadblock, so reaching sustainability will likely take more time, but “we” believe that “we” can be back to normal in six months or a year. A few think that “we” are in for a decade of economic difficulty.

The use of “we” covers up the different experiences in different communities. When listening to colleagues in organizations founded by and rooted in African American and Latino/a communities, I recognize that they hear talk of sustainability differently. They have learned to say what funders want to hear, but they translate the words into a different set of actions.

For example, I have encountered a handful of organizations in these communities that recently had applied for but did not receive a $1 million grant to serve pastors. Most of these organizations moved forward to develop and deliver as much as they could of the proposed program without the money. How? Mostly through unpaid labor. People affiliated with these organizations took on a second (and sometimes third or fourth) job to serve pastors. In economic terms, these organizations were investing sweat in place of money in order to do what was both most important and possible.

In financial terms, it looks as if these programs are doing great. In fact, they don’t seem to need the grant money. But when we listen to their stories, it is clear that valuable ministry is being performed by exhausted leaders.

The white-culture organizations where I have worked talk about priorities. These organizations have the privilege of deciding how to serve according to the financial resources available. But I have observed many organizations that are part of African American and Latino/a communities prioritize according to the needs of their communities and the world. The leaders of these organizations do what is needed regardless of the money.

How can I learn from this dedication and not participate in taking advantage of it? One element of privilege is not recognizing the impact of categories like sustainability on those without privilege.

This realization has made me more careful when planning a collaborative project with organizations from different cultural, racial and ethnic communities. For example, I now ask partners about pay equity across the project for the same work. I don’t assume that because employees at my white, dominant-culture organization are paid a fair wage, all the collaborating organizations are able to do the same. How do we plan the project so that people are paid equitably?

In fact, the concern starts in the planning phase. What creates the conditions so that all the organizations involved in planning a project have the resources to do the planning? Those with wealth have the option of choosing to shift their efforts to a new project. Those with no resources have to double up on their work to do something new.

If a project is underway, what would it be like to count the labor of these leaders as part of sustainability? What would it be like for donors to see that they are matching a contribution of labor and recognize that effort as part of sustainability?

What would happen if donors recognized the vast disparity between the assets accumulated by white-dominant organizations and white families when compared with African American and immigrant institutions and families? What if the funding levels were calibrated to address these disparities? What would happen if organizations in these communities had significantly longer to develop sustainability plans for donors?

In the midst of economic challenges, more complex and nuanced definitions of sustainability need to be used. All who donate and benefit from donations can learn to pay attention to the needs in communities, as well as who can be supported to address these needs. Moving too quickly to asking a program to “pay for itself” can continue a cycle that takes resources away from long-disadvantaged people.

As a white leader, I must learn more about the challenges faced by my colleagues in different racial, ethnic and cultural communities and advocate for adjustments that provide a path to more equity. I must not leave all the weight for making this case on these leaders.