A missing story finds its way to the stage

Rhiannon Giddens had never heard of Omar ibn Said until Nigel Redden, then the general director of Spoleto Festival USA, approached her about writing an opera based on an enslaved Muslim man who had lived in North Carolina.

The Grammy Award-winning musician was curious, and also slightly angry. Growing up in North Carolina, this was not part of the history she was taught, Giddens told a Charleston, South Carolina, audience at the festival this past spring.

Said was not included in history textbooks, or even in libraries, until the Library of Congress acquired his autobiography in 2017. The 15-page manuscript, penned nearly 200 years ago when Said was 61, is the only known surviving autobiography written in Arabic by an enslaved person in America. After several translations into English, the original manuscript lay forgotten for nearly a century in a dusty trunk in Virginia. Its recent rediscovery has sparked interest among academics — and creativity onstage.

The emergence of this man’s autobiography comes in a fraught season of reckoning over whose stories have been told and whose have been ignored in the narration of American history. At the same time, while some American Christians have begun to more fully acknowledge the faith’s role in racial oppression, others have come to more fully embrace a nationalist vision rooted in division and racism.

The opera “Omar,” which premiered at Spoleto this past May, offers a window into the defining role Said’s faith played in his extraordinary life, undergirded by his own telling.

For Giddens, the invitation from Redden to bring the story to the stage was a welcome challenge. The multi-instrumentalist and classically trained opera singer is known for her genre-crossing talent — an Americana-roots-country-folk-classical mashup, plus a voice that knows no bounds and an intellect to match — all fueled by her passion for recovering and celebrating African American musical history.

The MacArthur fellow and co-founder of the Carolina Chocolate Drops, who in 2020 was named artistic director of the Silkroad Ensemble (her predecessor was Yo-Yo Ma), has embraced the fretless banjo in recent years, an instrument with African roots and ties to the kora.

Giddens’ songwriting has delved deep into narratives of her enslaved ancestors, imagining their lives and stories in heart-wrenching tunes like “At the Purchaser’s Option” on her acclaimed album “Freedom Highway,” nominated for Album of the Year at the 2017 Americana Music Honors & Awards. As her website says, she uses her art “to excavate the past and reveal bold truths about our present.”

Whose stories are silenced in your community? How can you discover these stories?

So re-imagining Said’s life, especially for the operatic stage, and especially for a premier music and arts festival, was right up Giddens’ alley. “Opera,” she said, “is a format for big stories.”

Big is one thing, but Giddens knew a project of this magnitude required a creative partner, and Michael Abels, a composer best known for his scores for the Jordan Peele films “Get Out,” “Us” and, most recently, “Nope,” was the partner she wanted. Though the two had never met, much less worked together, Abels jumped at the opportunity.

“Our collaboration was immediate, from our very first meeting,” said Abels, who embellished Giddens’ libretto and initial melodies with his orchestration. He and Giddens set about researching just who Said was and why and how his long-buried story of spiritual journey, religious integrity and tenacity could make compelling opera.

This was all in early 2018, shortly after the Library of Congress digitized Said’s autobiography, which initially sparked Redden’s idea for the opera. The plan was for the new work to debut at the 2020 Spoleto Festival USA, coinciding with its host city’s 350th anniversary and the anticipated opening of the International African American Museum.

The pandemic, however, delayed the production for two years. In the meantime, as Giddens and Abels and their production team continued to collaborate virtually, George Floyd was murdered, and the world, already in the midst of one pandemic, was riveted by the racial reckoning and unrest of another.

It was as if the tattered, yellowing daguerreotype of Said — an elegant elder in a black suit, his hand resting regally on a cane, his heavy brow and haunting eyes staring straight at us — was imploring, “Here I am. Here we all are. Listen up.”

What stories have you uncovered that need to be told “big”? Who in your community has the talent and audience to tell big stories? What does collaboration with other storytellers look like in your community?

Who was Omar ibn Said?

While most people, like Giddens, had never heard of Said, Islamic scholar Hussein Rashid had.

Rashid, a Muslim American who earned a doctorate in Near Eastern studies from Harvard, has taught in higher education, including at Columbia University and Virginia Theological Seminary. He is a consultant on religious literacy and cultural competency, with a focus on Islam and popular culture.

“In the study of Islam in the United States, there are only a couple of early figures we have primary source documentation on, and one is Omar,” said Rashid, who provided historical and religious context to the opera’s creators.

What is known about the historical Said is slim, based on 15 or so texts, including letters and verses he inscribed, his autobiography, documents from the family who owned him in his later years, and other historical records.

“I wish to be seen in our land called Africa, in a place on the river,” Said wrote in a letter dated 1819. In his autobiography, he states that he was born in Futa Toro (now a part of French Senegal), “between the two rivers,” although the exact location remains unclear.

He learned Arabic from his uncle and was educated in Muslim schools, memorizing passages from the Quran. He was 37 when “infidels” attacked his village in 1807.

“A big army came, and they killed a lot of people,” he wrote. Said was sold to “a Christian man who bought me and walked me to the big ship in the big sea.”

After spending a month and a half at sea, a scene depicted in the opera by wrenching historical sketches of ship hulls stacked with human cargo, he arrived in Charleston at Gadsden’s Wharf — less than a mile from where his namesake opera would be staged. He was on one of the last slave ships to sail into the city before the trans-Atlantic slave trade was outlawed in 1808.

After his initial enslavement by a “wicked little man,” likely a rice plantation owner near Charleston, Said fled and escaped to Fayetteville, North Carolina. There he was caught and jailed.

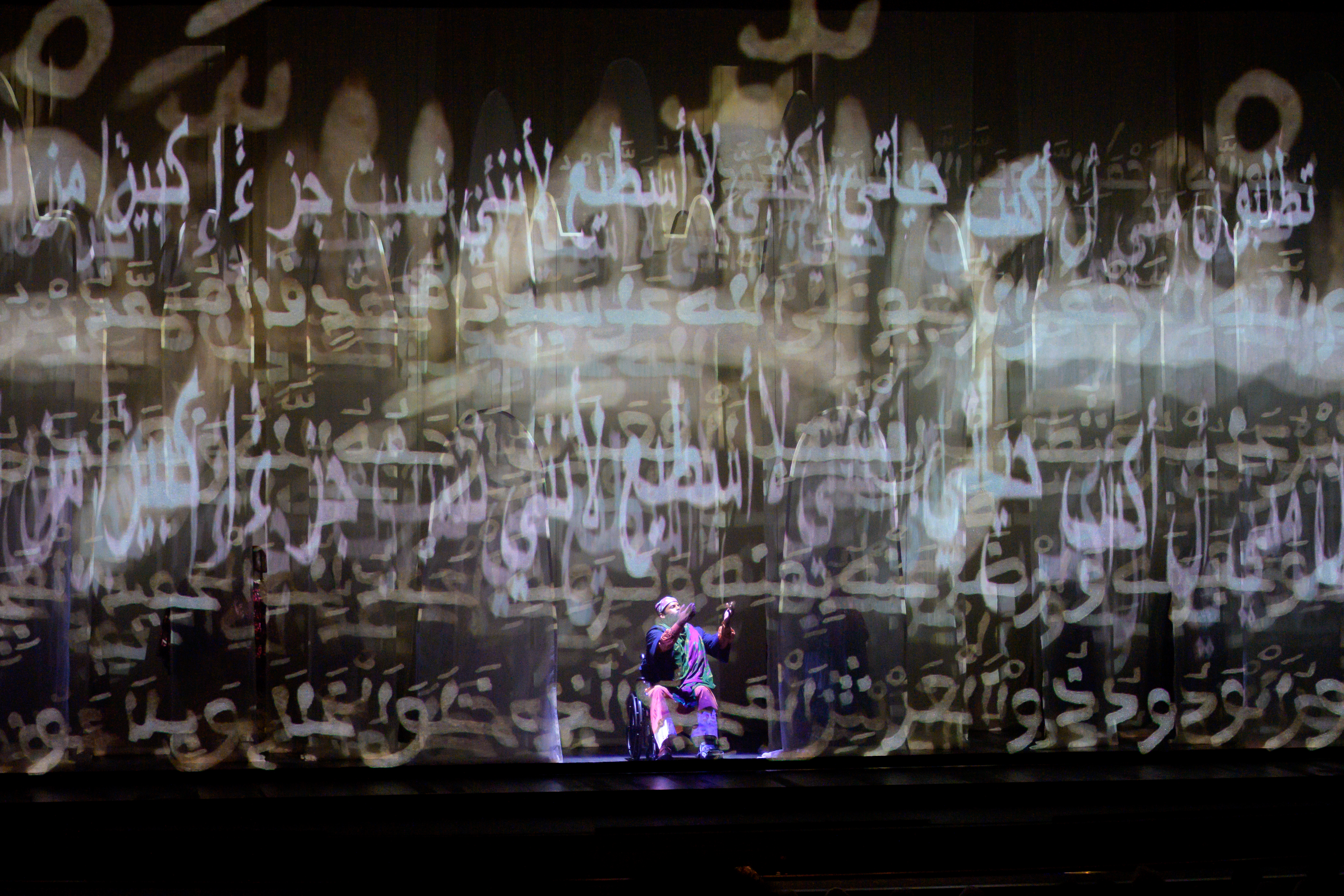

Said used bits of charcoal to inscribe verses from the Quran on his cell walls. His exotic calligraphy, mysterious and untranslatable to the local white population, piqued the curiosity and interest of many, including the sheriff’s son-in-law, a wealthy planter named James Owen.

For the next two decades, Said lived and worked as a house servant for the Owen family.

“I continue in the hands of Jim Owen, who does not beat me, nor calls me bad names, nor subjects me to hunger, nakedness, or hard work,” his autobiography recounts.

Given his education, piety and position as an elder, Said was afforded special status. Owen, a devout Presbyterian, gave him an Arabic Bible and took him to church, where he was eventually baptized.

As the abolition movement gained traction and fears of slave uprisings spread, whites like Owen believed that successfully converting Africans to Christianity could justify slavery. When Said was given a tablet of cream-colored paper and asked to write his story, he understood the delicate line he was treading.

“I am Omar,” he wrote in his elegant script, opening his autobiography with lines from the Surah Al-Mulk.

“In the name of God, the merciful, the compassionate. May God bless our Lord Muhammad …” These, too, are the opening lyrics of “Omar,” which Abels set to the pulsing, resonant, drum-heavy rhythm of the earliest known African melody that enslaved people brought to America — “a very deliberate choice,” Abels said.

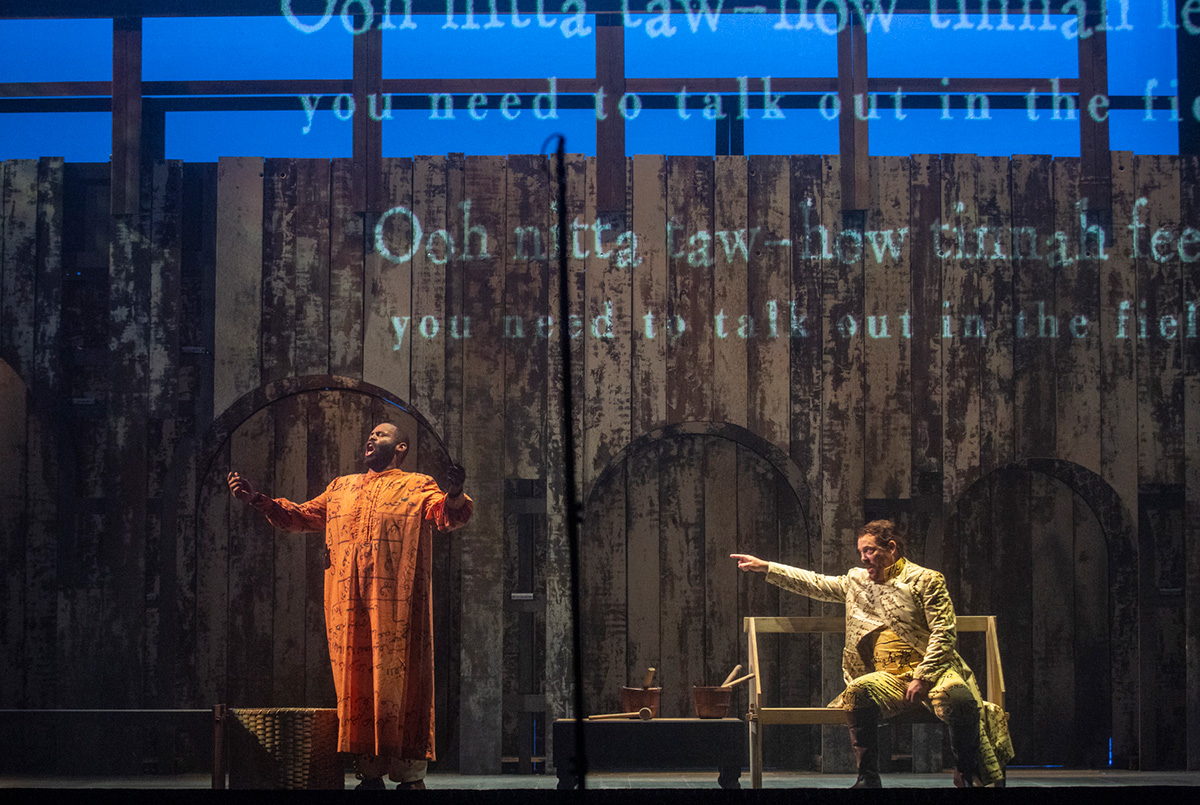

As the curtain rises, elaborate Arabic script dances across a translucent scrim. The text takes center stage, both in the scene design and in the opera’s breathtaking costumes. Said’s handwriting transforms from a series of written characters to a main character. It is given life.

Who are the students of the peoples that make up your community? What can you learn about the heroes of the people’s faith, families and homelands?

Richness of the religious landscape

To scholars like Rashid, who serves on the advisory board of the Doris Duke Foundation for Islamic Art, one of numerous funders of the opera, Said is historically significant “because figures like Omar help disabuse the notion that enslaved people were ignorant savages,” he said. “He challenges the mythos of the good of enslavement.”

Said’s life and faith also shed light on the high percentage of Muslims — estimated at 1 in 5 enslaved Africans — who were in the United States.

“Omar’s text also demonstrates the reality of religious fluidity,” Rashid said, noting that he quoted from both the Quran and the Psalms. “Yes, he’s praising Jesus, but no, that doesn’t mean Omar converted. Jesus is revered as an important prophet in Islam.”

Rather, his referencing Christianity points to Said’s intelligence and resilience. He understood that, despite his elevated status, he still wrote as a vulnerable captive; he needed to please his master.

“Said was protecting himself,” said Muhammad Fraser-Rahim, an assistant professor at The Citadel and, like Rashid, a consultant to the opera team.

Said embodies the fact that “American religion expresses itself in many ways,” Fraser-Rahim said. “This isn’t whirling dervish Sufism. Being a Muslim from Senegal is different from being Muslim in Tunisia.”

Basing an opera on Said’s life “challenges this idea of Islam as ‘other’ and Muslims as ‘hyperboogey man,’ as has been prevalent post-9/11; it shows that, in fact, Muslims have been here all along, and their legacy has helped shape this country,” Fraser-Rahim said.

“What Rhiannon did and what the opera has done is offer these wonderful glimpses of the richness of our religious landscape. It contributes to our imagination of what American religion can be.”

And for Giddens and Abels, for the cast and audiences, it expands the landscape of what opera can be.

How does the viewpoint of the privileged hide the identity of people in your community? What does it look like to make the invisible visible?

Music as spiritual practice

Imagining the real Said and his life, his suffering, his faith, his understanding of this new world in which he was violently thrust was “a very spiritual process,” Giddens said in a talk about creating the opera. “We can only try to evoke the spirit of Omar [through] what we have of his, passed down to us.”

Abels shares similar beliefs about the creative process.

“Writing music is a spiritual practice,” he said. “Music comes from a higher power, and the best music never feels like you’re writing it, just transcribing it, so I’m trying to get myself out of the way. My assignment is to bring it to the world.

“‘Omar’ was and is just a really good example of that, because of the subject matter. I can have that same experience in writing a film score, but for ‘Omar,’ it is ultimately a spiritual journey. That’s what the piece is about.”

Abels’ score weaves Western, more European orchestration when characters like Owen, the plantation owner, are singing with music that draws on slave melodies, spirituals, ragtime, early jazz and music that came from the Muslim diaspora.

“That added a kind of peace to it,” Abels said. “When Omar was praying and centered in his faith, the music conveys the sense of spiritual grounding he felt. As a non-Muslim but one who understands how faith provides solace and grounding, that’s where I was coming from.”

Abels recounted watching members of the audience during the second night’s performance, especially a number of people wearing head coverings and Muslim clothing. At the end of the opera, the chorus leaves the stage and, while chanting, processes into the aisles.

“Their chanting starts small and grows, then dies away very slowly, a centuries-old technique called a circular canon, like a round. Very meditative, by design,” Abels said. “The theatrical side of me loves ending a performance with a bang, but Rhiannon and I felt this was not the time to do that.”

As he watched these audience members, it appeared to Abels by their hand gestures that some were worshipping.

“That they would feel this was a spiritual place to them said everything,” Abels said.

“Omar” opens next at LA Opera, Oct. 22-Nov. 13, 2022, and then May 4-7, 2023, at Boston Lyric Opera. The opera is co-commissioned and co-produced by Spoleto Festival USA and Carolina Performing Arts at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Additional co-commissioners include LA Opera, Boston Lyric Opera, San Francisco Opera and Lyric Opera of Chicago.

What are the musical styles of your community? How do you listen to those styles, and what are you learning?

Questions to consider

- Whose stories are silenced in your community? How can you discover these stories?

- What stories have you uncovered that need to be told “big”? Who in your community has the talent and audience to tell big stories? What does collaboration with other storytellers look like in your community?

- Who are the students of the peoples that make up your community? What can you learn about the heroes of the people’s faith, families and homelands?

- How does the viewpoint of the privileged hide the identity of people in your community? What does it look like to make the invisible visible?

- What are the musical styles of your community? How do you listen to those styles, and what are you learning?

I come from a long line of singers. I remember as a child gathering around the piano with my parents to sing old gospel hymns.

My mother and father loved to sing, and they turned my three brothers and me into a pretty good quartet. In my preteen years, people discovered that I was a boy soprano, so I got invited to sing for various civic clubs in our small town.

Singing was also part of my church life. We went to church often, and I quickly figured out how to survive the long sermons: get ready for the next hymn.

On Sunday evenings, my favorite part of the service was the 15-minute “Hymns We Love to Sing.” Members of the congregation would call out the numbers of hymns, which we’d sing with gusto.

When I turned 18 and it came time for me to consider a vocation, some suggested that I pursue a career in music. Would I choose ministry or music? Was there a way to choose both? I decided then that I would use music as part of my ministry.

Thus, for my entire career, I’ve been a singing minister — in church choirs, symphony choruses, ensembles, a folk band. I occasionally sing in the middle of my sermon. (When preaching about healing, how can one resist bursting forth with, “There is a balm in Gilead to make the wounded whole …”?)

I’ve reflected often about why singing captures us and won’t let us go. What I’ve concluded is that singing inspires hope. In these times of tumult and strife, where do we find hope? I think that when a poetic text is set to a lovely melody, that combination becomes irresistible — and motivational.

It may be a simple text such as, “We shall overcome. … We’ll walk hand in hand. … We shall live in peace.” Singing this tune draws us together; it’s a galvanizing force that lifts activists and marchers in the struggle for justice.

Singing forms community. While solos have their place (and I’ve done my fair share of them), I’ve long preferred the chorus over the individual voice. Why? The corporate song draws us into a unity, a communal cohesion, connecting us with each other through times of stress and distress.

When we sing, we can’t do anything else. We get “lost in wonder, love and praise,” as the hymn “Love Divine, All Loves Excelling” says. The singing takes over and invites us to stay in the present moment, thus giving us access to vitality and aliveness.

As a pastor, I found that singing is another way to connect with members of the congregation. Songs express blessing, forgiveness, delight and lament. When singing makes us come alive, “that is the area in which we are spiritual,” as David Steindl-Rast writes in “Music of Silence.”

Go to any church funeral, for example, and listen to the congregation sing, “A mighty fortress is our God, a bulwark never failing,” and you will hear hope singing through grief. Likewise, grief is tempered when we sing, “O God, our help in ages past, our hope for years to come.”

We sing the pain, and we sing through the pain. We sing with fervor until the song gets inside us, and the song sings us.

Through the years, various parishioners would confide to me that they were unsure about what they actually believed. They had doubts and questions that prevented a clear, verbal statement of their faith. When I heard these concerns, I usually asked whether they had favorite hymns.

“Make a list of your favorite hymns,” I would tell them, “and you will see what you believe.” Hymns have a way of moving into our hearts and staying in our memory banks; they become a storehouse and expression of our faith, theology and spiritual commitment.

“Amazing Grace” is often at the top of the best-loved hymns list. It’s a compelling affirmation: “Through many dangers, toils and snares, I have already come. ’Tis grace hath brought me safe thus far, and grace will lead me home.”

After singing these hymns for so many years, I often find an old tune popping into my consciousness at some unguarded moment. I then sing from memory a welcome word — the song is singing me.

A few years ago, I was sitting in the silence of a Quaker meeting for worship when a Friend rose and said, “This may be out of order, but I know Mel is here, and I’d like to call him out to sing ‘How Can I Keep from Singing?’”

I was startled, but I recovered and did as requested, singing from memory a version of the 19th-century hymn based on Psalm 145. It’s a call for hope in the midst of lament:

My life flows on in endless song;

Above earth’s lamentation,

I hear the real though far-off hymn

That hails a new creation.

No storm can shake my inmost calm

While to that rock I’m clinging;

It sounds an echo in my soul

How can I keep from singing?

On another occasion, I was walking in a forest when an old hymn started singing me. I found myself singing, “Are you weak and heavy laden, cumbered with a load of care?” (The lovely word “cumbered” means “hindered” or “obstructed.”)

This hymn kept on singing me, until I got the message: release the stresses you’re carrying. As I finished my forest walk, I said aloud, “Thanks. I needed that.”

Theologically, it seems clear to me that God has chosen music as a primary vehicle to reach us. God rides on music. Singing becomes a spiritual practice; it wakes us up and gives us a surge of life and hope.

This speaks even to those who have difficulties with church. One Sunday, a stranger appeared in worship. At the church door, he said, “I used to go to church a lot, and now I don’t. The only thing I really miss is the singing.”

I understand what he was saying. In our worship, Scripture, the liturgy and the sermon can bring insight and inspiration. But as my aged mother once said to me, “I’ve been listening to sermons all my life, and I don’t remember a one of them.”

Yet she remembered many hymns and sang them often from memory. Those hymns sang her — and sustained her — through many ups and downs. And after a lifetime of deriving hope and joy from the music, how could she keep from singing?

Joe Richman wouldn’t want to document his life for a year with an audio recorder, but that doesn’t stop him from asking others to.

As the founder of Radio Diaries, he has asked dozens of individuals ranging from prison inmates and judges to nursing home residents and adolescents with Tourette syndrome to keep audio journals of their lives for up to a year.

With Richman’s guidance, they have recorded daily musings, interviewed people they know, and captured the sounds of their everyday lives. And Richman has edited the raw audio to make radio documentaries for National Public Radio’s “All Things Considered.”

Those documentaries include “The Last Place: Diary of a Retirement Home,” as well as the series “Prison Diaries” and “Teenage Diaries.”

“My natural tendency is to hide a little bit behind the tape,” said Richman, who worked for the NPR programs “All Things Considered,” “Weekend Edition Saturday,” “Car Talk” and “Heat” before founding Radio Diaries more than 15 years ago. “I’ve always done pieces that emphasize the tape and the characters and the stories. The mission is to get people to speak in their own words and to tell their own stories.”

Radio Diaries also produces more traditional radio documentaries that interweave historical recordings with present-day interviews. Among its productions are “The WASPs: Women Pilots of WWII”, “Strange Fruit: Voices of a Lynching”, and “Becoming Nelson Mandela.”

Richman spoke with Faith & Leadership about how to tell stories, how to draw out other people’s stories, and the role that storytelling can play in institutions. The following is an edited transcript.

Q: Why radio documentaries? What do they offer that you don’t get in print or in film or on television?

Radio is such a medium of characters. We really hear people in a way that I think can be truer than the way we read about them or the way we see them on television or film. The voices tell a lot, and there is a lot between the lines.

It has been said that radio is an intimate medium. In good radio storytelling, you can get to know people in a way that feels sometimes deeper than in any other medium.

It doesn’t mean it always happens, but there’s an opportunity for that. There is something about the magic of the real power of radio that can really transport you into people’s lives.

Q: You have produced radio diaries involving teenagers and the elderly. What have you learned about the different ways younger people and older people tell their stories?

One of the great things about teenagers is that they feel like whatever they say, it’s important. Once you start doing the stories with grown-ups, they don’t always feel that way. What about my life is worth broadcasting to 12 million people?

We did a diary in a retirement home years ago, and that was really interesting. Some of the elderly there had done very remarkable things and certainly led interesting lives, but they said, “Why would anyone want to hear my story?” You don’t have that problem with teenagers for the most part.

Q: How do you get people comfortable enough to share their stories?

It’s not really about getting people to feel comfortable; it’s more about getting people to feel like there’s a reason to share their stories.

Q: Why should they share their stories?

I find there are different reasons. For Laura [who had cystic fibrosis and was 21 years old when she recorded her life for “My So-Called Lungs”], she wanted to live on. She knew she was going to die at some point, and she wanted her memory to live on.

For Thembi [a 19-year-old in South Africa with AIDS who recorded her life for a year for “Thembi’s AIDS Diary”], I think her interest was the stigma inside Africa about AIDS. She was young and beautiful, and when she would tell people that she was HIV positive, their jaws would drop, because they had these stereotypical images. And no young people were talking out about AIDS, so for her it became a political issue.

For others, it may just be about sharing their personal story. Every story is different, but when people feel like their story is being treated respectfully and with dignity, I think all of us want to share our stories.

Q: You have said that you have developed a radar for detecting authentic and real stories. How does someone go about developing that radar?

I think that radar comes from knowing the people. When I go out and do a quick interview with others, it’s a lot harder to tell what is really them versus if I’m following someone for more than a year and I have 40 hours of tape.

I can also tell because so much of it is between the lines. It’s not just the words they say. It’s how they say it. It’s what they don’t say. It’s the pauses. The information between the lines — that stuff is really important. It’s the emotional truth, and sometimes it’s hard to pick up on that or get a feel for where that lies unless you have enough time and enough tape.

Q: For many of the documentaries you produce, you hand a recorder over to someone and ask that person to record his or her life for six months or a year. Why this approach? Why not just interview the person or follow him around for an extended period?

There’s something so intimate about radio. When you can cut out that middleman — me or the reporter or the host — and have someone like Thembi or Laura talk directly with the listener, it puts them in the passenger seat.

Someone is stuck in traffic driving home from work, and all of a sudden they are hearing this young girl from South Africa with AIDS. They’re not hearing me tell them about her. They’re hearing her, and there is something so much more direct about that. It’s about getting people to know people that they don’t know.

Q: Why is that important?

There is something incredible about being able to listen to and experience other people’s stories. It’s like having this passport into other people’s lives that you wouldn’t otherwise even meet. There’s no more important thing you can do than to get other people’s stories.

What is that quote? “An enemy is someone whose story you haven’t heard.” Fear and hate and misunderstanding all come from not seeing people as real human beings. Stories help to make people three-dimensional.

Q: How do you draw out other people’s stories?

You have to be curious. Without a doubt, though, the most important thing when you’re interviewing someone is to make it a conversation so it’s not just questions and answers, but it’s a dialogue. When people feel like it is a conversation, they feel like they are being listened to.

Q: What are the keys to being a good storyteller?

There are different kinds of good storytellers. When I first started doing diaries 15 years ago, I thought I had a pretty good idea of who was a good diarist and who wasn’t. As the years have gone by, I have less and less of a good idea who’s a good diarist and who isn’t, because it’s not necessarily just the funny, extroverted good talkers. They are one kind, but then there are also the ones who are quiet, intimate, and they draw you in and make you lean closer to them.

Everyone is good at different things. Some are good at recording sounds and scenes. Some are good at interviewing people. Some are good at telling a story with all the details and color and anecdotes. And some are good at sitting on their beds late at night, reflecting on their lives or the world.

Partly my job is about getting people to play to their strengths and pushing them with the things they’re not as good at and not as comfortable doing. But mostly — about what makes a good storyteller — it’s about honesty and curiosity.

Q: What should people in leadership positions keep in mind about storytelling?

Everything is about stories. It’s the way we communicate and the way people receive information. So whether it’s radio storytelling or any kind of storytelling, the stories we tell about ourselves are important, too. We’re so used to the stories of celebrities and politicians, but it’s really important to make sure to hear the stories of ordinary people.

Q: What role should storytelling play in institutions like the church?

The act of interviewing people and having people share their stories — you can’t lose. It’s a valuable thing, whether it’s through a microphone or a pen or a video camera. Just the act of someone listening and paying attention — having your story heard and respected and paid attention to — is a powerful thing, both for the storyteller and for the listener.