What does mentoring look like?

When Jack Causey moved to a neighboring city to pastor their First Baptist church, I waited for a couple of months and then called.

“You don’t know me, but I know you. Could we meet?”

It sounds like a note passed in middle school, but we were adults. I was a pastor in my 20s in need of guidance. Jack was entering his fourth pastorate. Each congregation had thrived under his leadership.

Jack’s preaching and worship skills were such that he frequently designed worship services for and spoke at youth events and on college campuses, which were then tough crowds. Jack had been the pastor-adviser to a campus group when I was an undergraduate. I did not know him personally, but I was part of the crowd that followed him.

At lunch, I mentioned needing to learn from him, and Jack immediately rejected the idea of being a mentor or coach. We could be friends and peer pastors, he said. He was willing to meet once a month. We did that for about five years. Later, Jack agreed to facilitate an intensive, yearlong leadership development group with me. We did that for a decade.

Jack died in November, 37 years after our first lunch. On Facebook, because that is the social media of my generation, I read hundreds of clergy testifying to Jack’s impact on their lives. At his memorial services, I learned that Jack had gathered peer groups before that phrase was known in our denomination.

I wondered: What was so special about Jack Causey? How did he come to influence so many people?

When I asked to meet with him in 1986, I was drawn to his skills as a storyteller and his experience as a pastor. After years of facilitating groups with Jack, I realized that his superpower was listening.

Everything from the intense gaze of his blue eyes to the forward lean of his posture communicated that he heard me. If he knew something that would help, he would offer it. If not, he would give enough feedback to demonstrate that he was hearing me and was with me. Person after person in the memorial service testified to receiving the gift of being heard.

One of the reasons Jack resisted the title “mentor” and was hesitant about being a “coach” is that he was humble. He thought those titles suggested that he had some technique or wisdom. He would say he offered kindness. He offered friendship.

That description might suggest that he was passive, but Jack had a keen sense of how to put what he was hearing and noticing into action. As a congregational pastor and elected official in his denomination, he honed the skills of good leadership. He moved toward conflict and sought productive resolutions. He worked to establish consensus and held himself and others accountable to goals.

He was a master at setting and keeping boundaries. Before smartphones, Jack never carried his calendar with him, because he wanted to have space to think through any commitments being asked of him. At the church, the only key that he claimed to carry was to his office. He did not want to be distracted by being drawn into doing others’ work. At our first lunch, he set a rule that we would each buy our own meals (although when I was his “boss,” he did let me pay).

His leadership and service engendered long-lasting loyalty. A couple of years ago, I arranged to visit Jack. That morning, I learned that his beloved wife, Mary Lib, was gravely ill and had been admitted to hospice that day. Jack wanted me to come to the hospice house.

When I arrived and asked a volunteer to be directed to Mary Lib’s room, the lobby quickly filled with six or seven more volunteers. They asked all sorts of polite questions about how I knew Mary Lib and Jack. I was from out of town, and they were determined to protect the Causeys at this vulnerable time.

Jack heard the ruckus and came out to assure the group that we were old friends. I was deeply moved by the mutual care that had developed between the Causey family and the community and had endured for more than 20 years after his retirement from First Baptist.

After I left the pastorate near Jack, I launched a center to support congregations and established a leadership development program for clergy in their first five years of congregational ministry. Another mentor of mine guided me in setting up the framework to serve about a dozen clergy per cohort. I was near the same age and experience level as the participants and needed a partner who could bring decades of experience to the program in a humble and inviting way.

I approached Jack, and we co-led the yearlong program for about a decade. A few years into that process, Jack retired from the pastorate and devoted his vocational energy to staying in touch with the participants. Over time, the participants spread the word about how helpful a conversation with Jack could be.

My contribution to Jack’s post-congregational ministry was to create conditions for him to offer friendship and encouragement to more pastors. Jack knew this was his calling, and he asked me how he could do it in an accountable way. Eventually, our denomination also set up a structure for Jack’s work. When I read all those Facebook posts and comments, I took some comfort in knowing that our institution and denomination had been part of creating the opportunity for Jack to befriend more people.

Jack Causey’s ministry reminds me of the impact that happens when someone is committed to what Jack called friendship and I know as mentoring. It can happen one-on-one through the individual’s initiative. The impact can be expanded by thoughtfully created structures and conditions. But at the heart of it is a person deeply committed to careful listening and mutual respect.

Jack may be right that “mentor” is not a helpful word, because it commonly represents a top-down relationship. But he brought wisdom to our relationship and to countless others that many in my denomination will miss.

Thanks be to God for Jack. May we all be inspired to offer friendship to colleagues after his example.

The unmistakable scent of curry permeates the spacious commercial kitchen in Richmond, Virginia’s East End, where a half-dozen teenagers in spotless white chef coats are sharpening their culinary skills while feeding their community.

The teens scrub, peel and chop several buckets of turnips and radishes donated by a nearby farm, the rhythmic ka-THONK, ka-THONK of metal knives against plastic cutting boards broken only by whispered guidance from chef Duane Brown: Slow down, slow down. Take your time. And watch your fingers. Yep, yep, perfect.

Brown, a graduate of the Culinary Institute of America, has been meeting weekly since November with some of these teens, teaching them first the art of “mise en place” — having all needed tools and ingredients organized and close at hand — before branching out into food prep and production. On this particular evening, Brown will show them how to braise the chopped-up root vegetables in a curry sauce before pouring them over a bed of steamed rice and dividing them into 50 separate meals for low-income seniors and families in a nearby apartment complex.

At one end of a prep table, 16-year-old Malachi Sottile scrutinizes a red onion before peeling and finely dicing it. Sottile said he’s always enjoyed cooking. He was learning some tips from his grandmother before enrolling in the culinary training class, which falls under the auspices of Church Hill Activities & Tutoring, or CHAT, a nonprofit where Brown serves as the director of workforce development. Sottile’s skill set has expanded considerably over the last seven months.

“At first, it was challenging, keeping track of all the new information,” Sottile said. “But after a while, you get the hang of it.”

Alongside their knife skills, class participants pick up life skills, learning the importance of showing up on time, asking for help, working with a team, focusing on a task and communicating clearly, Brown said. At the end of the day, participants are gaining not only the ability to earn a paycheck but also the confidence to try new things, solve problems and advocate for themselves.

In addition to offering culinary training, CHAT operates three distinct businesses that also serve as training grounds for young people in an economically depressed part of Richmond: a coffee shop and cafe, a silk-screening studio, and an urban farming outfit that includes a cutting-edge hydroponic grow operation. Those businesses employ about 20 young people, most between the ages of 16 and 22; last year, 51 young people either worked for one of CHAT’s enterprises or participated in its training programs, said Hannah Teague, the director of marketing and communications for the organization.

“Ultimately,” she said, “as an organization, we want to create more and more opportunities for students and young people to help them grow personally, spiritually, socially and academically so they’re ready for whatever’s next.”

Which programs and ministries in your community help people advocate for themselves and their neighbors?

‘A rebalancing of the scales’

CHAT has what Teague calls a “scrappy origin story.” It launched in 2003 after a couple moved into the Church Hill neighborhood and turned their front porch into an informal gathering place, where neighborhood children could safely hang out and get some help with their homework. They were part of a wave of Christians, mostly white, who began moving into Church Hill from the suburbs, hoping to advance the cause of racial reconciliation and redevelopment in the state’s capital city.

That couple has since moved to South Carolina. But with guidance from the community, CHAT has expanded its scope, formalizing its after-school program, opening a fully accredited private Christian high school with priority given to low-income students from Richmond’s East End, and adding workforce training.

While there are spiritual components to CHAT’s programs, students can be of any faith — or no faith, and the organization doesn’t consider evangelism to be a primary focus. But, Teague said, “Christianity is in the ethos of everything we do.” In addition, she said, in a place that was once the capital of the Confederacy, CHAT’s programming is meant to prioritize the Black experience and center Black voices.

Brown said the seeds of CHAT’s workforce development piece were planted around 2005 or 2006 when the nonprofit launched Nehemiah’s Workshop, a woodworking operation where students handcrafted coasters, charcuterie boards, tables and rocking chairs. Jobs in the neighborhood were scarce, he said, and CHAT wanted to offer young people a “wholesome” activity where they could learn a lucrative trade.

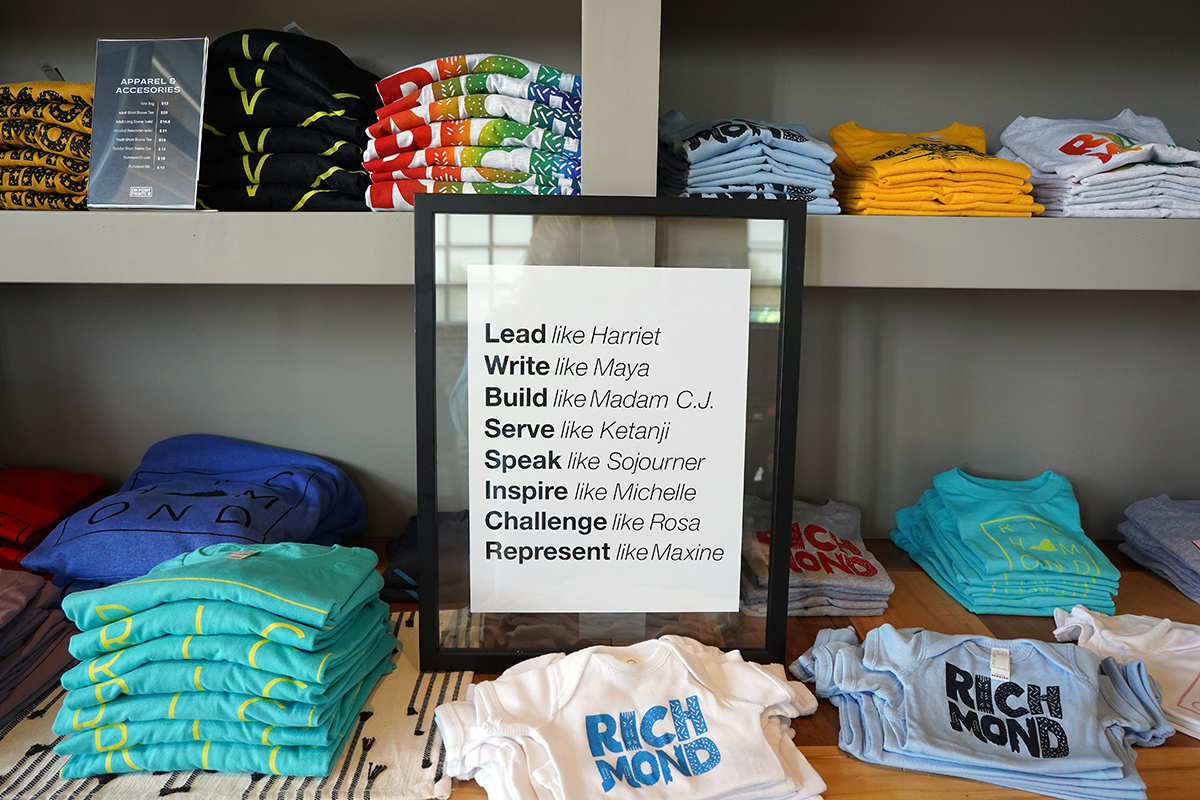

Next came lessons in sewing and silk-screening, which led to the creation of On Point Prints, a screenprinting studio that produces everything from tote bags and T-shirts to tea towels and hoodies.

In fall 2017, CHAT opened its primary food service training facility, the Front Porch Cafe, which is a breakfast and lunch spot housed in the Bon Secours Richmond Community Hospital’s Center for Healthy Living. There, about a mile north of CHAT’s main office, diners settle into comfy blue easy chairs while enjoying pastries, coffee, tea and sandwiches.

Framed photographs of neighborhood residents enjoying their front porches adorn the exposed brick walls of the interior. And some of the ingredients used in the cafe’s meals are grown at Legacy Farm, an urban gardening project, which encompasses a few parcels on CHAT’s quarter-acre property and some space in a church-owned greenhouse nearby.

Whose voices are centered in your work? Whose voices are minimized or missing entirely?

In addition, CHAT was invited last year to participate in a three-year pilot project, where students learn how to grow microgreens using hydroponic equipment. The equipment was purchased and installed by Dominion Energy, and maintenance and seeds are donated by Richmond-based Babylon Micro-Farms.

The entire nonprofit has an annual budget of about $3 million, most of which comes from private donations. Roughly 20% of that is set aside to support workforce development, said Jonathan Chan, CHAT’s executive director.

CHAT’s businesses are not motivated by profit as much as by a desire to equip young people with life and professional skills, so the enterprises are not expected to be self-sustaining. The goal, said Brown, is for the revenue from each business to cover about 80% of its expenses.

While not focused purely on money, the effort is still strategic. The organization paused Nehemiah’s Workshop to assess and research similar trainings and to gain a better understanding of the industry trends and student interest. The primary focus is on aligning with regional workforce goals and technology. Some of the workshop’s woodcraft items remain for sale online, as are items from On Point Prints. Shoppers can also pick up On Point’s tote bags, T-shirts and onesies inside the Front Porch Cafe.

All of the businesses have popped up at local farmers markets and neighborhood festivals to showcase their wares. The culinary trainees have hosted cooking demonstrations and tastings for family, friends and cafe customers. And, in anticipation of sourcing its lettuce from the hydroponic farm this summer, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts invited the Front Porch Cafe staff to host a pop-up event in late May, debuting its Summer Crunch salad, a mix of green leaf lettuce, quinoa, carrots, lentils, almonds and an apple cider vinaigrette that will be featured in the museum’s cafe.

Rebranding and exploring

Because the organization has evolved quite a bit over the last two decades, Teague said, CHAT is working on a rebranding effort that draws clear connections between all of CHAT’s initiatives: the social-emotional work of the after-school care program, the academic focus of the high school, and the vocational aspect of the workforce training initiatives. The organization is also exploring how best to leverage its connections to alumni so they can share their talents and life experiences with CHAT’s current participants.

Gentrification within the Church Hill neighborhood is also a challenge CHAT is trying to address, Chan said. Rising property values have meant that some of the families the organization has traditionally served have been pushed into neighboring communities, leading CHAT to expand its own service area beyond Church Hill proper into Richmond’s East End — even as far as neighboring Henrico County.

Right now, CHAT’s main office, along with On Point Prints and the Legacy garden, stands in the heart of Church Hill, within walking distance of several elementary schools and a Boys & Girls Club. But that may need to change down the road as families are displaced, Chan said.

The young people who participate in CHAT’s programs are full of promise, and their drive challenges false notions the general public may have about people who live in the East End of Richmond, Chan said.

How do your organization’s structure and work evolve when situations change? How do you transition out of what is no longer possible and refocus on what is?

“I think we want people to have a sense of the potential, assets and gifts of our students and that we have a rebalancing of the scales to do. We want people to interrogate their own assumptions of how the world works,” he said. “If they have negative perceptions of Black and brown students, the people who live in this area, we want those to change, to be disrupted, so they can learn how they can be part of God’s work of justice.”

‘They truly want to help you grow’

In a cramped room at the rear of CHAT’s headquarters, Timond Billie, 19, is flooding a silk-screen frame with all the colors of the rainbow to create one of On Point Prints’ popular tote bags. A senior at Church Hill Academy, CHAT’s private high school, Billie said he started working at the shop in October 2021 after hearing about it from his twin sister, Jamea, who had completed a six-week summer internship there.

How does your organization contribute through disruption to God’s work of justice?

Billie said he hopes to pursue careers in music production and real estate. The networking and marketing skills he’s picked up at On Point will help with both of those pursuits, he said. And learning about color schemes and design should come in handy when it comes to flipping houses, he said.

“I didn’t know there were so many colors — or that you could make colors out of other colors,” he said, laughing, as he pulled a squeegee through the ink, pushing the colors through the screen and onto the canvas bag beneath his tray.

Initially, Billie said, he was anxious about interacting with other people. But On Point manager Stephanie Albert was so welcoming, encouraging him to work at his own pace and to just be himself, he said, that he quickly felt comfortable. And after selling items at the neighborhood farmers markets, he doesn’t worry about chatting with strangers anymore, he said.

“I used to be really shy. But you’ve gotta break out of your shell,” Billie said. “Now, I’m confident with it.”

Like Billie, most of those who apply to CHAT’s training programs or to its job openings hear about those opportunities through word-of-mouth. Brown said he’s in regular contact with local schools, pastors and community liaisons in nearby housing complexes, letting them know when positions and new training programs open up.

In terms of tracking the progress of the program’s participants, Brown monitors whether they show up consistently and on time, how present they are when it comes to listening to instruction and completing tasks, and how well their communication skills progress, he said.

Though each workspace is a little different, Brown has accessed some youth-specific tutorials and webinars through the Federal Department of Labor’s WorkforceGPS, he said, and has gotten good advice from Catalyst Kitchens, a national network of nonprofits and regional workforce boards that operate cafes and restaurants offering job training and life skills exposure. Brown said he also makes use of industry tools, like keeping track of how many culinary trainees go on to earn their ServSafe certification through the National Restaurant Association.

The top measure of success, however, is how well CHAT instills confidence in those who participate in its workforce training initiatives, Brown said. Many of the young people who work for CHAT’s enterprises have never held a job before, he said, and many of them have little, if any, exposure to life management skills. Some face challenges with housing and transportation or are self-conscious about their struggles with math or reading comprehension. But Brown works hard to earn their trust and make CHAT a space where they feel safe enough to be honest about their needs and their goals. It’s rewarding when they share their victories with him, he said.

“There’s a point in the mentoring process where they’ve launched or moved on and you kind of stop hearing from the students,” Brown said. “And then you hear, ‘Hey, I’ve got this job interview.’ Or, ‘I got my ID.’ Or, ‘I got an apartment and a full-time job.’ And they’re demonstrating that they’ve got what they need and that they feel self-sufficient.”

Mareesha Randolph, 20, said she never really felt free to express herself or speak up about how others made her feel when she worked in retail.

“I kind of just stood in the shadows,” said Randolph, who applied for barista training at the Front Porch Cafe after a friend who was familiar with CHAT recommended it.

On her first day of work, Feb. 27, she met fellow trainee Rashá Coleman, 19, and the two have basically been finishing each other’s sentences since then. Both women said they were encouraged to ask questions and try new things, something they hadn’t experienced at their previous jobs.

What’s the word-of-mouth about your organization and its work within the community?

“With other jobs, they just throw you right in. And back in my old job, they used to stand over you,” Randolph said. “Here, if you need help, they’re here for you, but they’re not all in your face. Over here, it’s OK to make a mistake.”

She said she still gets nervous every time she hands a customer a cup of coffee, worrying about whether she nailed the order or not. But it’s gratifying when the person takes a sip and smiles or gives her a nod of appreciation, she said.

“You shouldn’t let fear stop you from doing things you could be great at,” Randolph said. “It’s OK to try new things. That’s how you figure out what you like and what you don’t like.”

Randolph said she’s been surprised by how much she’s learned, everything from how to steam milk “so it’s not screaming at you” to how to create latte art — she’s recently mastered making a heart pattern.

She hopes to use the practical skills to get a job at a coffee shop in New York when she moves there in the fall for acting school. But the other experience she’s gained — speaking with members of the public at pop-up events, working during the high-pressure lunch rush, learning how to read customers’ body language and respond with empathy — will be invaluable in any work environment, she said.

“They’re just so friendly, and you can feel that they truly want to help you grow. They gently push you into the areas you need,” Randolph said. “And the way they do it, you didn’t realize you really needed those skills until you have them.”

Questions to consider

- Which programs and ministries in your community help people advocate for themselves and their neighbors?

- Whose voices are centered in your work? Whose voices are minimized or missing entirely?

- How do your organization’s structure and work evolve when situations change? How do you transition out of what is no longer possible and refocus on what is?

- How does your organization contribute through disruption to God’s work of justice?

- What’s the word-of-mouth about your organization and its work within the community?

My daughters were in early elementary school 15 years ago, when the mass shooting at Virginia Tech took place 70 miles down the road from our home. I was midway through reading “Bridge to Terabithia” to a class of second graders when this then-unusual form of violence ripped through their young imaginations.

The school’s guidance counselor and I used Katherine Paterson’s novel about a child dealing with tragedy to help the students — several of whom knew some of the Tech victims personally. We talked about their experiences of grief, loss and fear in the aftermath of that tragedy.

The unusual has now become commonplace: mass violence leaves young and old alike grieving almost weekly in our nation. But it is young people — those now in their 20s and those coming along behind them — whose coming-of-age is marked by the commonplace reality of mass violence.

It’s important to find civic and political cures for these forms of violence and to provide for the emergency mental health needs of young adults today. But I wonder: Could we also look upstream, to prevent problems and maintain the mental health of our young before crises hit?

This first generation to come of age in the spiritual-but-not-religious era is not without spiritual practices; the internet supplies plenty. But young people are often without communities of support, companions on the way to engaging in practices that build resilience.

Companions remind us of the value of spiritual practices. They help us create new ones, and they help us stay engaged in meaningful forms of soul care that are also the deepest forms of self-care.

The brain research of Lisa J. Miller and others shows that spiritual practices mitigate the severity, duration and negative outcomes of depression. The work of spiritual healers, movement chaplains, campus ministers and other seekers who are finding a path forward can provide deep wells of sustenance to those struggling.

Recently, I commented that the bridges to these wells of sustenance are broken. A friend who founded a campus ministry corrected me; they’re not just broken, he said: “It’s as if someone poured oil in the chasm and lit it on fire.” We no longer expect young people to come back to the institutions that once stewarded spiritual practices.

It is my hunch that soulful practices that acknowledge anxiety, restore calm and remind weary travelers that they are not alone might be radically helpful, if not curative, if made more visible and accessible to young people these days.

These wonderings led me to create Our Own Deep Wells: Bringing Soulful Practices to Campus, an initiative set to launch in Virginia early this year. This learning platform will help collegiate life professionals — such as those who train resident assistants and those who assist in first-gen retention — to integrate diverse soulful practices into their group facilitation.

Drawing on the expertise of young leaders, scholars and practitioners across the country, this initiative seeks to build on the success of the mindfulness movement, creating more access to diverse spiritual practices that create mental health-friendly cultures on college campuses.

It grows out of conversations I’ve had over the past year with people working on the front lines of the mental health crisis on college campuses. One talk at a time, I reached out to friends who work with college-age students to ask, “What’s helping?”

Tasha Gillum, the coordinator of the Bonner Leader Program at the University of Lynchburg, shared a practice I told her about with her students the first time they gathered after the shooting at Club Q in Colorado Springs.

The practice is called “rainbow basking,” and it involves centering oneself in the dancing light of a rainbow — created by a prism in one’s home or scouted out in the stained glass of a chapel or church sanctuary.

After sharing this practice, Gillum asked her students what practices help them rally when they feel depressed. What helps them maintain their equilibrium, grieve or simply get through the end of another stressful semester?

Their list was long, creative, playful and heartening:

Gifting others; splurging on others; complimenting others; writing notes of gratitude; spending time with others over meals, with or without conversation; going for a drive with all four windows down and music blaring; going for a drive to look at nice houses; shopping; feeding myself; meditating; praying; listening to mood-based playlists; taking a long hot shower with music playing; binging crime documentaries, “Grey’s Anatomy” or videos of veterans coming home; people-watching; napping; petting puppies; hobbies; art and crafts; talking with a trusted friend; time in nature; walks at sunset; having a daily schedule; writing in a planner; journaling feelings; breathwork; silence; cooking; baking cakes; stress cleaning; yoga; lifting weights; running; coloring; crying; crying while watching animal videos; lying on the ground to get grounded; and stargazing.

Making the list is in and of itself a practice of deep self-care. Reminding ourselves and one another of resources — even those that seem trivial or self-indulgent — may create a breadcrumb trail back to hope-mustering practices.

Binge-watching or shopping may not qualify as a soulful practice to you, but one young adult said that curling up in bed to watch Netflix was a way of honoring her introvert self by saying no to multiple competing invitations.

Alone, any one of these acts may or may not fit the classic definition of a spiritual practice. But I am inclined to define “soulful practice” broadly and to invite young adults to imagine: What elevates a simple act of self-care to soul care? Or better yet, what excavates it, allowing it to draw us down, to settle us in body and soul? What emboldens or reminds us to make a soulful practice part of our routine, a daily ritual or a weekly one, alone or shared with a friend or larger community of friends?

In the days after the shooting of four football players and another student at the University of Virginia, I reached out to Karen Wright Marsh, the executive director of Theological Horizons, a Christian campus ministry there. Visiting over a cup of tea, we talked about the vigils there.

Sadly, college-age students are well-versed in what to do in the immediate aftermath of a crisis. Candlelight prayer services and roadside memorials are second nature. U.Va.’s iconic Beta Bridge — typically showcasing declarations of love and birthdays — was within hours painted with the jersey numbers of the slain and adorned with photos, flowers and offerings to the departed.

While this generation of young people knows well practices for the immediate aftermath of crises, helping them find resources for the longer haul of healing — and the healing of our culture of violence — requires gentle exploration.

“We are turning to candlelight, quiet togetherness, the reading of the Advent scriptures,” Marsh said. “I don’t ask, ‘How are you’ but reach for deeper questions like, ‘Have you seen something wonderful today?’ or, ‘What got you out of bed this morning?’”

Marsh is a historian of Christian practices. Her first book, “Vintage Saints and Sinners,” winsomely illuminates the lives of 25 historical figures who guided communities through difficult times. Her second book, “Wake Up to Wonder: 22 Invitations to Amazement in the Everyday,” comes out this year and similarly explores voices from the past who hold offerings for today.

It is no surprise that she would look backward to find a way forward. “There is power in turning toward stories of other violent and grievous times, to hear the witness of people who held fast, who asked our questions, from whom we can borrow faith,” Marsh said. “Our tragedies are sadly a part of the human experience; we are not alone. We are part of a bigger story.”

As I continue to talk with friends who work on college campuses across the nation, the list of practices that help us find a place within the bigger story grows long. Rainbow basking emerged freshly and powerfully for me; I offer it below in hopes that it might bring solace or comfort to you or your community. Try it alone, or better yet, invite a friend to do it with you.

I can’t wait to see what practices emerge next from the deep wells of our shared traditions, mixed with the urgency of our times and the creativity of our collective wisdom.

Rainbow basking

Find a rainbow — in a college chapel, a local church, a sanctuary repurposed as a pub, or create a rainbow of your own with a prism and free sunlight.

Situate yourself within the rainbow.

Let the rainbow dance on one part of your body.

Take seven deep breaths, eyes closed or open, one for each day of creation.

Take one more deep breath, for all the young lives we lose each day.

Feel the power of the rainbow dancing on you.

Give thanks for your body, just as it is or as it is becoming.

Give thanks for your sensuality, how you delight in touch, smell, taste, sound.

Imagine the rainbow affirming and blessing you.

Lift up in your imagination loved ones or friends who struggle to find safety, affirmation or self-acceptance because of their gender identity or sexual orientation.

Imagine the rainbow affirming and blessing them.

Lift up those who have died because of gender oppression.

Lift up those who struggle from depression or anxiety.

Welcome any feelings that arise, knowing they will ebb and flow.

If you are alone, hug yourself.

If you are not alone, hug yourself, and offer a hug to someone else.

Bask in this rainbow as long as you wish.

When you are ready, go on with your day.

If you are hurting, find a safe person to reach out to.*

* The SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration) National Helpline, 1-800-662-HELP (4357), TTY 1-800-487-4889, is a confidential, free, 24-hour, 365-day-a-year information service in English and Spanish for individuals and family members facing mental and/or substance use disorders. This service provides referrals to local treatment facilities, support groups and community-based organizations.

While this generation of young people know well practices for the immediate aftermath of crises, helping them find resources for the longer haul of healing — and the healing of our culture of violence — requires gentle exploration.

A team of people keeps me healthy in ministry. Spiritual director, colleague group, friends inside and outside the church, therapist — each of these companions plays a part.

But it had been a while since I had a mentor.

In my 40s, having been ordained for several years, I became that person less experienced colleagues sought out for guidance on navigating the ordination process and leading a parish. I knew how “the system” worked. I had witnessed enough conflicts, made enough mistakes, midwifed enough new ministries to feel qualified in offering encouragement, coaching and timely cautions.

Then about a year ago, I found myself in my 50s, contemplating what I expect to be my final decade of active, full-time ministry. Newly vaccinated against COVID-19, aware that it was impossible to predict all the ways this pandemic would reshape the church, and seeing glimmers of hope in coalitions forming to seek justice and offer mutual aid, I knew I needed a different kind of companion. I needed someone to help me navigate the new landscape. Someone less invested in shoring up what had been and more open to imagining what could be than was the tendency for “experienced” people like me.

I needed a mentor. Specifically, a mentor younger than myself.

What is sometimes called “reverse mentoring” has been around the business world since the 1990s. First introduced so that younger workers could bring older executives up to speed on the internet, the practice is now valued for less technical reasons. Younger mentors are now sought out for their perspectives and insights, not just their technical expertise.

That was the case for me. I wasn’t looking to be coached on optimizing social media or setting up breakout rooms on Zoom. I wanted a conversation partner to help me imagine sustainable ways to pastor and encourage disciples of Jesus at a time when the relationships at the heart of the church, wounded by pandemic separations, were more precious than ever.

My mentor, Caleb, is a person I mentored about a decade ago, before he was ordained. We both like to wonder out loud; we are fond of asking, “Why?” “What if …?” and even, “Why not?”

In addition to being separated by a generation in age, we have enough differences in gender expression, ethnicity and class background that our perspectives vary in fruitful ways.

We live close enough that it’s easy to meet once a month for coffee, although we’ve used Zoom when inclement weather and COVID restrictions have required it. Usually, I have something in mind I want to discuss; often, I’ll start thinking about a topic a week or so before we meet.

Sometimes I ask about his ministry with young adults. Learning what they’re doing is instructive for me as the interim priest-in-charge of a medium-sized parish of mostly older adults. Like our 20-something friends, we’re also facing a new stage of life.

Caleb emphasizes practices, like teaching mindfulness and contemplative prayer, rather than institutionalized “programs” that may not be sustainable. And he consciously sets aside time for his ministry partners to ask open-ended questions about faith, the Christian tradition, and how Jesus and the communion of saints can be their daily companions.

My parishioners are just as hungry as his to reconnect with God and each other; if they weren’t pondering deep and challenging questions before the spring of 2020, they certainly are now. So my mentor reminds me to open up spaces to pray together and to offer our grief, hopes and questions to God and each other.

He also reminds me to make time for fellowship, simply to enjoy each other’s company. A remark Caleb made early in our relationship, “Consider the lilies,” has become a refrain for me. It’s a reminder not to let anxiety dominate my ministry but to rest and trust in God, who creates beauty and delights in it.

We know that our arrangement is still relatively unusual. As Caleb has said, “It is often our culture’s approach (especially in the church and government) to presume that the world belongs to those who have accumulated the most of something, whether degrees, dollars or years of experience” — and further, to presume that these same people have “all the best insights regarding how to be in that world.” In subverting these assumptions, we believe we’re being faithful.

Caleb has reminded me that “overturning unhelpful cultural norms in the pursuit of Christ’s community and wisdom” is actually a part of our faith. Having entered adulthood during the Great Recession, he learned early that the quest for material security can be pointless and that our relationships are often our greatest wealth. Jesus teaches the same thing, and we keep having to relearn the lesson.

Our conversations move me to question assumptions. When I tell him my parish is aging — as are many churches — my mentor reminds me that a congregation filled with people in their 50s and older can be dynamic and that local retirement communities are a mission field.

When I share my congregation’s desire to incorporate younger adults, he asks how far they’re willing to go to be in community with 20- and 30-somethings. Is anyone talking about helping younger siblings in Christ retire their student debt?

If we typically think of a mentor as someone who helps you learn a system, mine does the opposite. He helps me get comfortable with the reality that some systems are breaking down, see the potential in the newness, and get real about what kinds of changes I’m willing to propose and guide.

That our relationship isn’t focused on him has brought my mentor some unexpected benefits. “Exploring the questions and concerns of a person with a longer career than me,” he has said, “gives me a fuller picture of what it means for a person to be in that stage of life and vocation.”

Engaging in conversations where we’re both vulnerable is more valuable for him than receiving whatever pieces of advice I think to dole out. Our conversations bless us both, in ways we hoped for and in ways we couldn’t have imagined. That sounds like the Holy Spirit on the move; that sounds like church.

He helps me get comfortable with the reality that some systems are breaking down, see the potential in the newness, and get real about what kinds of changes I’m willing to propose and guide.